NACo history: Counties emerge from pandemic

Key Takeaways

As county officials gathered in Washington, D.C. for the 2020 Legislative Conference, news from China buzzed in the background. Regardless of whether they were public health officers, word of a fast-spreading respiratory virus had a growing number of attendees concerned. Some wore surgical masks. Health Policy Steering Committee Chair Phil Serna, a Sacramento County, Calif. supervisor, eschewed handshakes for an elbow bump as a precaution against spreading a disease that few understood.

King County, Wash. Executive Dow Constantine arrived in Washington, D.C., and immediately flew back to Seattle upon the news that the first domestic death attributable to COVID-19 had been recorded in his county.

President Donald Trump, making the first appearance by a U.S. president at a NACo conference in 24 years, brought with him to the conference CDC Director Robert Redfield to address county officials’ concerns. Trump had invited several thousand county officials to visit the White House during his term, giving elected officials new levels of access to the executive branch and NACo an opportunity to engage with more county officials.

When attendees returned home in early March, few knew they would likely not be leaving their communities for roughly a year as they grappled with a public health and economic crisis that few if any could prepare for as the COVID-19 pandemic spread throughout the United States.

The nation’s 1,900 local public health agencies responded with varying guidance regulating the size of gatherings, limiting commercial activity and trying to pierce the fog of uncertainty with guidance from the CDC, National Institutes of Health and other authorities. Many county agencies coordinated testing for COVID-19 when tests became available.

As NACo president, Douglas County, Neb. Commissioner Mary Ann Borgeson heard from many county officials in those first few months.

“I had daily conversations with people on the phone or on Zoom,” she said. “A lot of people called for advice, or to trade stories, asking how other counties were managing the pandemic.”

County hospitals were inundated by patients, and some coroners and medical examiners had to secure refrigerated trucks to manage the overflow in their morgues as casualties mounted.

Counties moved their operations online to ensure continuity of service. They also worried what the decline in economic activity would mean for their tax revenues that funded support services that were seeing dramatic increases in demand.

As the economic effects of local limits were distributed unevenly across the workforce, counties took the initiative to distribute food and supplies to help residents survive.

The pandemic placed tremendous strain on county officials who bore enormous responsibility for the well-being of their residents. Onondaga County, N.Y. Executive Ryan McMahon suffered vision problems because of stress and exhaustion.

The totality of the county effort was hard to see at the time, but looking back, Borgeson was amazed at what she saw.

“I was proud that counties showed that we don’t shut down. We just find a way to do what we need to do to get the job done,” she said. “I was just so extremely proud of the NACo staff, getting people together daily on phone calls to give them the best information, sometimes just peace of mind or a chance to hear their concerns and try to find answers.

“It was amazing to see the weekly calls with the media, the close coordination with the administration. I think we showed that we can continue to be strong for all counties, even through a pandemic.”

The CARES Act, passed in March 2020, supplied some financial relief, though it was a state-oriented bill that only offered direct funding to 119 counties whose populations topped 500,000, with smaller counties forced to access funding through their governors’ offices.

Meanwhile, NACo’s “We Are Counties” campaign highlighted the frontline roles that county personnel played in staffing nearly 1,000 hospitals, over 800 long-term care facilities, 750 behavioral health centers, 1,900 public health departments, emergency operations centers and 911 systems. The campaign showed the faces of the local civil servants who were keeping their counties running from home or six feet apart.

NACo had the foresight to purchase pandemic insurance for its events, which softened the financial blow of canceling the 2020 Annual Conference, scheduled for Orange County, Fla. Like everything else that year, a stripped-down conference was held online, with a fully remote Annual Business Meeting.

Counties met the challenge of the 2020 election, recruiting new poll workers to mitigate the risk to the traditional demographic who work on Election Day, older Americans whose age put them at elevated risk for serious COVID infection. County election officials expanded ballot access, installed drop boxes and navigated uneven state laws governing ballot-counting procedures. Elected officials of all kinds faced criticism, skepticism and in some cases harassment after a close presidential election, driving tremendous turnover in their ranks for years after.

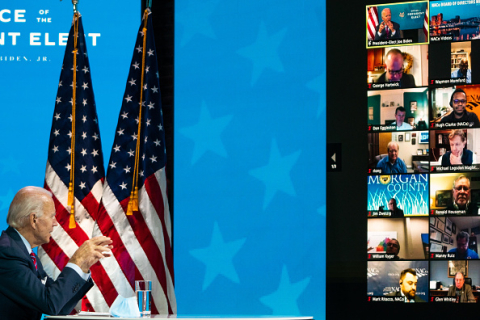

Joe Biden, who had been a mainstay at NACo conferences both as a U.S. senator and in 2015 as vice president, took office in 2021, leading a ticket in which both officers were county veterans. Biden had served on the New Castle County, Del. Council from 1971-1972 and Vice President Kamala Harris had served as San Francisco City and County district attorney from 2004-2011, as a deputy district attorney in Alameda County, Calif. from 1990-1998 and chief of the San Francisco career criminal division from 1998-2000.

American Rescue Plan Act

Throughout 2020 and early 2021, the need for additional COVID relief was apparent, and negotiations would continue through the end of Trump’s first term and into Biden’s. Along the way, the Senate changed hands, but throughout, NACo-engaged congressional leaders’ familiarity with local governments would be invaluable in shaping what would be the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA).

ARPA’s overall $1.5 trillion price tag was driven by economists’ contention that insufficient relief for state and local governments in 2008 prolonged the Great Recession and contributed to uneven recovery. Two provisions made all the difference for counties: First, the $65.1 billion — the largest federal investment in county government in American history — would be distributed directly to counties, with no need to navigate relationships with governors. And second, the money could also be used to backfill lost tax revenue as a result of the pandemic.

Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer (N.Y.), Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell (Ky.) and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) all committed to giving local governments equal footing with the states, though NACo CEO/Executive Director Matt Chase noted that their first draft proposal used the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) formula to distribute the money.

“We wanted it to be general aid and not a grant; they picked CDBG because it was really the most common trusted formula that got money directly from the federal government to local government, bypassing the states,” Chase said. “What they didn’t realize was that the CDBG formula is based primarily on the age of your housing stock, so it really benefited the Northeast and the industrial Midwest. It was very unbalanced for counties.”

“We had to start educating federal partners about what counties were doing to address the COVID-19 pandemic both immediately and in the long term,” said Eryn Hurley, NACo’s managing director for government affairs, who took charge of ARPA education and matters for county governments. “It really demonstrated how counties were on the front line of addressing the COVID-19 pandemic and not even just public health. There were so many other items that were exacerbated, housing, food and everything.”

NACo won support for a 50-50 share between cities and counties, with a key provision that consolidated city-counties could tap into both. Incidentally, all three congressional leaders represented consolidated governments. Pelosi served a San Francisco district, Schumer had represented New York City in the House prior to the Senate and McConnell was judge-executive of Jefferson County, Ky., which consolidated with Louisville in 2003.

“Speaker Pelosi was unbendable,” Chase said. “There were so many efforts by the governors to cut us out and to reduce our money, and Speaker Pelosi, in particular, was just a piece of granite. Sen. Schumer was a champion of directing money to the local level. The New York county executives and the New York State Association of Counties did a great job of articulating the challenges counties were facing. They played an instrumental part in building political support.”

“There was also tremendous continuity between the Trump and Biden administrations while we worked it out.”

When Boone County, Ky. Judge- Executive Gary Moore spoke to McConnell about getting aid directly to counties, he called upon the memory of General Revenue Sharing to show how the package would work. Although ARPA passed on a party-line vote, Moore said there was value in engaging the Republicans.

“We did have an impact with Republican senators because while they were insisting that they were opposed to the package, they understood that when it happened, it would be best to not go through the states. So, we all had an impact in educating and moving it.”

Counties had the leeway to invest their ARPA funding as they wished, supporting local businesses, bolstering food distribution systems for residents, offering grants to social service organizations and senior resource centers, providing housing assistance, public health and more.

As 2021 dawned, counties were part of the chain of custody delivering and distributing doses of the COVID vaccine that allowed the country to tenuously return to a pre-COVID time. The successful vaccine distribution allowed NACo to quickly plan a hybrid 2021 Annual Conference, with an in-person event held at the Gaylord National Harbor in Prince George’s County, Md. Located within driving distance of NACo’s Washington, D.C. office, conference planning staff were able to prepare for the conference while limiting their travel. Accustomed to planning conferences over much longer timeframes, NACo had once arranged an Annual Conference on short notice in Cook County, Ill. in 2006, but staff had one year to plan that, compared to three months in 2021.

Vice President Harris continued a growing streak for the executive branch when she spoke at the 2021 Annual Conference, and Biden would carry it on for three more years, addressing General Sessions at the 2022, 2023 and 2024 Legislative Conferences.

Connecting across the country

When schools went remote, doctors limited in-person appointments, small businesses adapted to web-based commerce and counties maintained services during the pandemic, nearly everyone recognized the limitations that high-speed internet connectivity posed to the world at the moment and where things would be evolving in the future.

NACo had already been pushing to verify the accuracy of internet service providers’ claims, introducing a smartphone app, TestIT, that allowed users across the country to test their internet speed from their counties. The Broadband Task Force, in 2020 and 2021, examined what counties must do to prepare for broadband, what stood in the way, how disparities in access affected their residents and how counties could prepare to compete in a global internet economy.

“Thanks to the pandemic, the universal need for broadband became reality overnight, rather than something that might have been 10 or 20 years in the future,” said Moore, the Boone County. Ky. judge-executive.

Boone County was one of the first in the nation to connect every home to high-speed internet service.

As the task force’s work began, Chair J.D. Clark did not have much experience with broadband, even as judge of the Wise County, Texas Commissioner’s Court.

“I left that experience knowing a whole lot more about broadband than when I started, but more specifically with a much better idea of what possibilities existed,” he said. “It gave me the right questions to ask, it gave me the right people to pull in the room to help change my framework for what good broadband looked like. But overall, the task force was representative of the best NACo has to offer —helping to equip county officials with the knowledge to address the problems that are affecting their communities. We saw broadband go from a luxury to a necessity, but NACo was already working on that when the rest of the world caught up.”

Exploring artificial intelligence

What does the future look like?

Is it a natural progression of the world we now know, or will it veer off in a new, unthinkable direction?

Those are two of the questions NACo’s AI Exploratory Committee addressed in 2023 and 2024 when considering the future of artificial intelligence, its applications and opportunities and its potential pitfalls to county government.

“I think government workers are just stuck in their ways a lot of times,” said Maui County, Hawaii Assessor Scott Teruya. “Rather than following procedures without question, a wide enough net by AI could find a better solution. When you have been going through B to get from A to C, maybe there’s a better way, and the human brain hasn’t comprehended it yet.”

For some counties, AI offers the potential to automate functions that take up staff time, increasing efficiency and sometimes accuracy and freeing personnel from mundane and frustrating tasks. The data analysis, on scales humans could only imagine, might provide new insights into the allocation of resources and service delivery.

Stephen Acquario was concerned about the consequences for public sector labor unions, which will want a say in how the employment world changes. As executive director of the New York State Association of Counties, he has been attuned to the nuances of a heavy public sector union state.

“There’s a sense that ‘We’ve always done it this way,’ and it’s hard to break that inertia,” he said. “The lack of understanding by most people will be the impediment to adopting it.”

Innovations in the field can develop so quickly that the committee’s report, the AI County Compass, instead focused on a framework for assessing the technology and providing county officials with a basic understanding of how to evaluate AI.

“I’m worried that a county will get itself into a contractual agreement that may not be favorable,” said Peter Crary, a committee member and senior manager of technology at the Texas Association of Counties. “I really do hope that we can give them guidance on what to do. If we can at least build guardrails and educate them on how to build the policies, what vendors are looking for, these are the questions you should ask.”

Frankly, residents may come to expect AI-enhanced services that they experience in the private sector. Peoria County, Ill. Administrator Scott Sorrel staked out the challenge for counties.

“The speed of evolution of the technology is going to be a challenge for county governments because they do not move at the pace of the private sector,” he said.

Chris Rodgers, a Douglas County, Neb. commissioner who made cybersecurity his priority as NACo president in 2012-2013, was concerned about the proliferation of misinformation and disinformation in what AI models learn, influencing their outputs. If counties perpetuate that bad information, it legitimizes it and could deteriorate a county’s trustworthiness.

“Once it’s out there, there’s no way you pull it back in,” he said.

Chase used generative AI to compose “The Marvelous Adventures of Countyland,” a rhyming children’s story about the functions of county government, as an example to elected officials of what is possible with the new technology but also illustrating some of the limitations inherent in AI, such as biases in assuming demographic details in illustrations.

Housing affordability

One of the long legacies of the Great Recession was the chilling effect on the housing market. Years before, Lake County, Ill. Commissioner Angelo Kyle made housing accessibility a focus of his year as NACo president.

It became clear in 2022 that housing affordability had reached a crisis, and every level of government would have to figure out how to make it easier to build housing. Will County, Ill. Board Member Denise Winfrey, then NACo’s president, created the Housing Affordability Task Force to articulate ways counties could do their part to encourage the development of affordable quality housing units. NACo worked with the Brookings Institution and the Aspen Institute to create a Housing Solutions Matchmaker tool, which analyzes demographic trends for individual counties, comparing them against their peers in the same state and other counties across the country.

The task force itself provided policy prescriptions for leveraging federal resources, land use reforms, regulatory adjustments, community engagement and more.

“Stable, quality housing is the foundation for better health, safety, education, a strong workforce, improved financial wellness, and lower demands on the social safety net,” Winfrey said. “NACo’s Housing Task Force is committed to meeting the moment and addressing our residents’ housing needs.”

National Center for Public Lands Counties

As the COVID-19 pandemic continued and urban dwellers sought more space, some fled to rural counties, with many occupying second homes in resort communities near national parks and recreation areas. Public lands soon saw themselves being “loved to death,” around the same time that wildfires in national forests sent plumes of smoke across the country. All of that converged to raise the awareness of the challenges public lands counties face in managing and funding operations.

Public lands counties, funded in large part by Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) and the Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Act, have a unique relationship with the federal government, with federal policy having a direct and dramatic effect on how those lands are used. Nearly 62 percent of counties contain federal land.

Some of those counties focus on resource extraction, some on outdoor recreation. Others are affected by the ease with which a president can increase or decrease the amount of public land covered by the Antiquities Act, which governs national monuments. They have economies all their own, and NACo and the Western Interstate Region created the National Center for Public Lands Counties in 2023 to study those economies, tell their stories and serve as a repository of knowledge for county leaders, including documents like natural resource plans and other strategic planning documents.

Sparked by the creation of the Local Assistance and Tribal Consistency Fund, counties voluntarily contributed funds for the center to demonstrate how the prosperity of public lands counties creates a more prosperous America, telling that story through traditional and new media.

“As a group, we have decades of experience working with public lands issues, but the problem with that is that it takes decades to build that up,” said Greg Chilcott, a Ravalli County, Mont. commissioner who was an early champion of the center. “By pooling our experience and building that repository of knowledge, we can help new officials in public lands counties speed up their learning curve.”

Craig Sullivan, executive director of the County Supervisors Association of Arizona, prizes the data and analysis the center has generated.

“We, as an organization, really believe in the importance of factual information and data-driven analysis to inform public officials,” he said. “It’s also important to tell the story of public lands in a way that people can understand, because the public lands story is very complicated. We’re already seeing foundational information coming out of the work the center is doing, things that would have helped me when I was trying to first learn about the issues.”

Disaster Reform Task Force

Repeated wildfires and floods in Sonoma County and elsewhere in California have shown Supervisor James Gore that federal disaster assistance policy, managed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, is broken. Resiliency and disaster preparedness had long been a priority for NACo leadership, particularly for presidents Linda Langston, from Linn County, Iowa, site of devastating floods, and Sallie Clark, from El Paso County, Colo., which suffered both wildfires and floods. Their advocacy reinforced the need for counties to perform mitigation work to prepare for an increasing number of natural disasters.

Gore named an Intergovernmental Disaster Reform Task Force to provide recommendations for policy reforms and best practices that improve disaster mitigation at the county level. Those aspects include direct technical support, reduced administrative burdens and public accountability.

With one-third of counties experiencing at least one disaster each year, the issue has reached a critical mass for change.

Meanwhile, President Trump opened his second term by establishing a council to assess FEMA and has mused about wanting Congress to dismantle the agency. Counties will offer their perspective on how federal disaster assistance should change.

“Reform of FEMA is very different from elimination of FEMA, with no more payments for public assistance,” Gore said. “If we have a cost shift where the federal government does not pay for debris removal anymore, we are fighting against that because our general funds cannot handle that. That is not a political fight. It’s an existential fight.”

Counties often carry millions of dollars in recovery costs while they await FEMA reimbursement.

Looking ahead

Soon after his term in Rensselaer County, N.Y. ended, former NACo President Bill Murphy moved to Georgia and went to work for PEBSCO and Nationwide, and his tenure there far outlasted the length of his time in county office. Approaching NACo’s 90th anniversary, he had lived another lifetime after leaving county government.

But he never lost touch with the formative years of his career nor with NACo. He remains a County News reader and looks with pride at the way NACo not only survived its near calamity but found its way through the challenges and away from the hazards facing any organization and set its trajectory.

“NACo was able to meet the challenge, sustain itself and grow into the wonderful organization that you have right now,” Murphy said in 2024. “It’s so much more multifaceted than when I was in office, and a lot of that is a function of having the revenue from the deferred compensation program to be able to do those kinds of things.

“I’m also proud they were able to keep the right perspective between the entrepreneurial nature of the organization and the lobbying nature of the organization and not let one crush the other, which frequently can happen, particularly when the entrepreneurial side crushes the other side," he noted.

“It’s obvious to me that NACo is held in very high regard by the people on Capitol Hill when we need their support for the things that are important to us," he said.

"But it’s also important to me that that NACo is seen as a resource for local governments at all levels. I know my commissioners here in Forsyth County attend NACo conferences, and they allow their staff to do the same thing. You have this coalition, this association of people of like minds dealing with similar problems. And no one of us is as smart as all of us, right?

“The more people we can bring to bear on a problem, the better off we are always going to be.”

Related News

NACo Hosts County Leaders in Washington, D.C. and Launches We Are Counties National Public Affairs Advocacy Campaign

NACo is hosting nearly 2,000 county leaders from across the country for our annual Legislative Conference February 21-24.

NACo leaders urge new attendees to connect, engage at Legislative Conference

Nearly 300 first-time NACo Legislative Conference attendees heard from a slate of speakers welcoming them to the event and providing some guidance.

County News

NACo pivots to data, problem solving in 2010s

As Matt Chase took the lead at NACo, counties showed the federal government they had the tools and the talent to be partners in solving difficult problems, from mental health issues in jails to substance use disorder.