Naake-led years bring stability, growth to NACo

At the end of his tenure, Executive Director John Thomas saw the birth of a major public affairs effort. The country observed National County Government Week between April 7-13, 1991, a celebration that later expanded to all of April in 2010, stressing counties’ role in the intergovernmental relationship with the federal government, cities, states and tribes. More than 80 counties and state associations recognized the week.

With county officials in attendance in the Oval Office, President George H.W. Bush signed a proclamation during the Legislative Conference:

“In recent years, more and more Americans have realized what many have known all along: That the answer to many of the problems before us can be found, not in bigger federal government, but in effective local leadership and cooperation between citizens and public officials at all levels. Indeed, we know the government closest to the people is truly government of the people, by the people and for the people. This is the essence of federalism and democracy, and it is key to meeting many of the challenges and opportunities before our country.”

As a testament to the organization’s recovery over the prior nine years, NACo received more than 200 applications to succeed Thomas, as he left to lead the American Society for Public Administration. The executive committee reached back onto NACo’s bench with Larry Naake, the executive director of the California State Association of Counties (CSAC), who had worked in NACo’s legislative affairs in the early 1970s and again in the early 1980s. The same Larry Naake whom Bernie Hillenbrand had entrusted the General Revenue Sharing lobbying effort in the 1970s.

NACo soon advanced some of its own to the federal government. Jim Snyder, a Cattaraugus County, N.Y. legislator and former NACo president, left county office to serve as director of intergovernmental affairs for President Bush. He noted a distinct lack of county awareness among his colleagues in the executive branch, and he sought to correct this.

“Some people in the White House didn’t know the difference between a county and a city. It was a shock to me,” he said in 2019.

Ten years later, President George W. Bush would also bring a county veteran in as director of intergovernmental affairs, former San Mateo County, Calif. Supervisor Ruben Barrales. That administration also included former Orange County, Fla. Mayor Mel Martinez, who served as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

Cooperative purchasing

When Naake returned to NACo, he left a small but reliable cooperative purchasing project at CSAC which his successor, Steve Swendiman, grew.

He soon recruited Swendiman, formerly a Shasta County, Calif. supervisor, to join NACo and bring his business sense with him.

“I was never a guy who wanted to lobby,” Swendiman said. “I always preferred the management side of things.”

Swendiman didn’t take a salary and lived on the road while he built NACo’s new for-profit Financial Services Center.

“That revenue went back into the organization, after the expenses, and really supported the concept that we don’t have to live just on dues,” Swendiman said.

The program, one of the first of its kind, took advantage of the economies of scale when bundling the needs of many counties to secure lower purchase prices. David Davenport invested $1 million to seed the program.

Swendiman is quick to credit Naake with navigating the elements at play.

“How do you create something that’s going to have a residual revenue flow to NACo? How do you do that without disturbing a nonprofit?” he said. “I think it was masterful.”

Swendiman also lauded Fairfax County, Va. Supervisor Gerry Hyland for giving cooperative purchasing the shot in the arm it needed, after pitches to other nonprofits to get in on the business were unsuccessful. Hyland won Fairfax’s purchasing director over on the service and before too long, Fairfax County and Los Angeles County were competing to do the most business, motivated by the 5% commission counties would earn.

The first major contract, with Office Depot, started at $2 million and grew to $700 million a year in seven years.

“It turned out to be our bread-and-butter program and it allowed us to do a bunch of other programs,” Swendiman said. Doug Bovin, a Delta County, Mich. commissioner who was NACo’s president when the Financial Services Center launched, was an evangelist for the program in Michigan. “It had the great dual benefit of making things more affordable for counties, while allowing NACo to be able to do more and be financially secure,” he said. “The savings were incredible. We could never have paid the same prices on our own. It was a way NACo could demonstrate its value on counties’ balance sheets.”

By 2018, U.S. Communities, as the cooperative purchasing venture was known, had grown in 23 years to $3.5 billion in annual sales, with 45 high-value national contracts. When partners in the business sold to a competitor, NACo sold its interest in the entity. Following a four-year non-compete agreement, NACo returned to the business, launching Public Promise Procurement and Public Promise Insurance under the rebranded NACo EDGE.

Back in the 1990s, a growing corporate membership program put vendors in front of county decision-makers, reflecting a nationwide trend toward more formalized public-private partnerships to address local and regional issues.

NACo also sold its option to purchase the building on First Street, netting $2.3 million. By 1997, NACo’s 15-year deficit was eliminated and two years later, the organization boasted a $5.5 million surplus.

Caucuses

Following the riots in Los Angeles in April and May 1992, then-First Vice President John Stroger, a Cook County, Ill. commissioner, called for an urban county summit later in May to meet with White House and congressional leaders.

“All you need to do is look at the Los Angeles riots to see how extensive a role county government plays in the life of urban America,” Stroger said. “It was the county health network that handled the emergency admissions during the unrest. It was the county fire department that fought nearly 1,000 fires during the days of the disturbance, and it’s the county that will have to deal with the overcrowded court system in the aftermath of thousands of riot arrests.”

The Large Urban County Caucus (LUCC) held its first regular conference in Washington, D.C. that fall. The caucus would meet every year but 2020 for its own conference with urban-centric themes. Programming and advocacy are oriented toward counties with populations of 500,000 and above.

Four years later, President Michael Hightower, a Fulton County, Ga. commissioner, established the Rural Renaissance Task Force, which later begat the Rural Action Caucus (RAC), led by Blue Earth County, Minn. Commissioner Colleen Landkamer, later a NACo president, and Harney County, Ore. Judge Dale White, previously a Western Interstate Region president. Landkamer later twice served as Minnesota state director of Rural Development for the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“At first it was just 10 or 20 of us — now look at it,” Landkamer said of RAC, a caucus that strains the occupancy limits of its conference meeting rooms. “The rural voice is so critical, and RAC members are getting so much information tailored to their needs they wouldn’t get anywhere else.”

In 2025, NACo’s board filled the gap by establishing a new Mid-Sized County Caucus.

Unfunded mandates

The 1990s brought a new opponent into view for counties: Unfunded mandates. President Bush decried them during his 1992 State of the Union address:

“We must put an end to unfinanced federal government mandates. These are the requirements Congress puts on our cities, counties and states without supplying the money. If Congress passes a mandate, it should be forced to pay for it and balance the cost with savings elsewhere. After all, a mandate just increases someone else’s burden, and that means higher taxes at the state and local level.”

In 1993, NACo found allies among the Big Seven public interest organizations, including the National League of Cities, the U.S. Conference of Mayors and the International City/County Management Association.

“We couldn’t have done this on our own. No one organization could do this without help,” said then-NACo President Barbara Sheen Todd, a Pinellas County, Fla. commissioner. “This wasn’t a matter of being against Congress, it was a matter of saying, ‘This is how it affects us when Congress makes decisions.’”

The Big Seven organizations held news conferences across the country on Oct. 27 — National Unfunded Mandates Day, including results from a survey by PriceWaterhouse that found that unfunded mandates cost counties $4.9 billion.

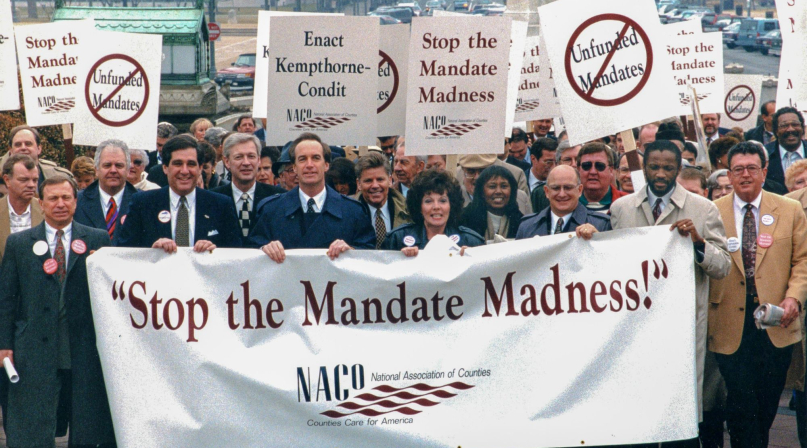

In 1994, Legislative Conference attendees marched to Capitol Hill for a “Stop the Mandate Madness” rally.

The effort got some help from the Republican Party’s Contract with America platform, which supported Sen. Dick Kempthorne’s (R-Idaho) Unfunded Mandates Reform Act. That bill was signed into law March 22, 1995, requiring that the federal government consult with elected officers of local governments to provide meaningful and timely input in the development of proposed rules containing significant federal intergovernmental mandates, consider a reasonable number of regulatory alternatives and select the least costly, least burdensome or most cost-effective option and include cost-benefit analyses for the rule.

Members in the driver’s seat

NACo’s legitimacy on Capitol Hill and around the United States is derived from our member-driven approach to policy development and advancement. Members on 10 policy steering committees recommend the agenda each year, giving the NACo board and staff direction in our government affairs efforts.

NACo members engage in many ways. Steering committee members dedicate an hour each month for calls, plus countless other ways, in actively offering ideas and feedback to White House and agency officials, congressional committee and coalition partners.

Other officials encourage their staff to attend conferences. Some large counties like Franklin County, Ohio bring more than two dozen staff to conferences. Some elected officials, such as those in Hanover County, Va. in 2005, made it a point in their public meetings to credit NACo with a particular program or solution they are employing. In recent years, Ramsey County, Minn. commissioners have been prolific in NACo leadership, serving as chairs of two steering committees and the Large Urban County Caucus in the 2010s. Commissioner Mary Jo McGuire went even further, serving as NACo’s president.

“It’s just part of our culture in Ramsey County to be involved in NACo and the Association of Minnesota Counties,” she said. “It was accepted, encouraged and supported. We make sure there’s a travel budget because it’s an investment in our county.”

McGuire credited the rest of her Board of Commissioners with shifting her responsibilities during her presidency to accommodate both roles.

“They were totally behind me because they knew what NACo means when we interact with the federal government,” she said.

Don Stapley ran for the NACo executive committee, and served as president in the late 2000s, to ensure that Maricopa County, Ariz., where he was a supervisor, had a voice in the national policy discussion.

“We knew the issues we faced were on a different scale than a lot of counties, but more often than not, they are still the same issues,” he said.

NACo’s Board of Directors is one of the largest in the nonprofit world. In addition to Board nominees from state associations, NACo’s president nominates 10 members, and NACo’s 24 affiliates also have seats.

States that have 100 percent NACo membership earn an extra seat on the Board of Directors, which motivates recruitment. Larry Johnson, a DeKalb County, Ga. commissioner, served as NACo’s ambassador throughout the state, before, during and after his presidency, helping to achieve 100 percent membership.

“I was able to show Georgians that NACo is a partner, that it complements everything we do on the state level,” he said. “We’re the eighth largest state in the nation, and it’s time for us to use that voice and to make the South even stronger. We have so many more Georgians involved in steering committees now, it’s a point of pride for me.”

NACo executive leadership displays an even higher level of commitment.

Randy Johnson, then a Hennepin County, Minn. commissioner, once made three trips to Washington, D.C. in the 1990s to testify before congressional committees in a single week while he was a NACo vice president, all while attending to his responsibilities at home. Riki Hokama’s presidency may have set a record for air miles traveled, owing to his home county of Maui in Hawaii. The distance and the time zone difference did not dull his passion for NACo advocacy.

“I wanted to try to visit every state while I was on the executive committee,” said Valerie Brown, a Sonoma County, Calif. supervisor who served as NACo’s president. “You meet so many people who put their time and energy into county government in states where they have different responsibilities and powers, it’s really fascinating.”

Randy Franke, a Marion County, Ore. commissioner who served as NACo’s president in the 1990s, regularly came home with napkins covered in notes from conversations with county officials at different state association meetings. “The travel was worth it for all of the impressions you get to make and receive from the members,” he said. “It’s a big country and there was always something to learn about what more we could be doing for counties.”

The runway through the executive committee has shortened since its six-seat process in the late 1970s to four today.

State and county policies often play a large part in when county officials can seek office, given county officials in some states face term limits. New Mexico, for example, limits officials to two terms, forcing candidates to pursue NACo office very early in their elected careers. Others have short windows of opportunity.

“When I thought about it, there was really only one year that it made sense for me to run, given what I wanted to do with my career,” said Bill Hansell, a Umatilla County, Ore. commissioner who served as NACo president.

Because they must be elected county officials to serve in a leadership capacity, some NACo officers have had to forfeit their seats after losing reelection. On the other side of the spectrum, King County, Wash. Executive John Spellman vacated his seat upon his election as governor in 1980. There are times when NACo has held simultaneous elections for multiple executive committee seats.

NACo moved away from a nominating committee in favor of direct elections for officer positions in the late 1980s.

Now, the executive committee consists of a second vice president, first vice president, president and immediate past president, along with four regional representatives, a format introduced in 2010 after a governance review committee led by San Diego County, Calif. Supervisor Greg Cox, who served as NACo president several years later. Those regional representatives, the West, South, Central and Northeast, help facilitate communications with membership on a regional level.

Competitive elections don’t necessarily lead to acrimony among candidates. During the three-ballot, four-way race for second vice president in 2018, the candidates bonded and became friends during and after the campaign. En route to the Western Interstate Region Conference in Blaine County, Idaho, Boone County, Ky. Judge-Executive Gary Moore and DeKalb County, Ga. Commissioner Larry Johnson found themselves sitting next to each other on the flight from Salt Lake City.

“We had both been through primaries the day before, so we had a lot to talk about there,” Moore said. “He was elected the next year, and we worked so closely together and became great friends.”

In the late 1980s, the election for the executive committee featured a matchup between Kaye Braaten, from 18,000-person Richland County, N.D. and John Stroger, of then-5 million-person Cook County, Ill. Braaten prevailed, and Stroger succeeded her.

“We got along very well even though we ran against each other,” Braaten said. “It was important for NACo to have that diversity. I was just a nurse from a farming community who ran to fix our roads and bridges, and he was from a county that did anything you could think of.”

In addition to biweekly calls, members of the executive committee committed to ambitious travel schedules to attend conferences by state associations of counties.

NACo’s leadership has featured noted diversity. Honolulu County, Hawaii’s Clesson Chikasuye was NACo’s first Japanese American president in 1970. Gladys Spellman, of Prince George’s County, Md. was NACo’s first woman president in 1972. Charlotte Williams, a Genessee County, Mich. Commissioner, was NACo’s first African American president in 1978, and Santa Fe, N.M County Commissioner Javier Gonzales was NACo’s first Hispanic president in 2001.

2000 election

The level of scrutiny over county-run elections reached a peak in November 2000, when the balance of the presidential election hung on the “butterfly” ballots distributed in Palm Beach County, Fla.

NACo and the National Association of County Recorders, Election Officials and Clerks formed the National Commission on Election Standards and Reform to develop policy recommendations for Congress, states and counties. The commission’s report, delivered in May 2001, addressed a variety of areas of concern and recommended best practices for dissemination throughout county election offices.

“One good thing that has come out of this year’s election is that people have started talking about the role of counties in the electoral process,” said King County, Wash. Councilmember Jane Hague, then NACo’s president and a county elections official earlier in her career.

September 11, 2001

While the entire country, and even the world, was transfixed by the enormity of the day, counties were at work, cooperating with state and federal officials.

Flight 93 crashed less than 10 miles from the home of Somerset County, Pa. Commissioner Pamela Tokar-Ickes.

“On that day, we sort of divided all of the responsibilities that fell upon the county of Somerset,” Tokar-Ickes said in 2022. “And we did what needed to be done. One of my fellow commissioners worked very closely with the coroner’s office. Another one of the commissioners really assisted with all of the central purchasing requirements and the things that were needed. And I was tasked, really, immediately, with working on memorialization.”

Three days later, the Somerset County courthouse was home to a massive memorial service, drawing thousands for one of the biggest gatherings in the county’s history, including family members of Flight 93 passengers.

Knowing the site would soon become a national memorial, the county coordinated with the local historical society.

The response to the crash of United Airlines Flight 93 fell to county government. The county was responsible for coordinating with the coroner’s office the recovery of the remains and the purchase of everything that was needed at that site for recovery.

“Everything from lip balm and sunscreen to the individuals who needed to be mobilized to actually search the site for human remains, everything,” Tokar-Ickes said. “The Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency team told us: “This is your responsibility from start to finish. We just want you to know that. Nobody’s going to come in here and do this for you. This is the county’s responsibility.

“The county coroner held the crash site for more than a year and the county hired sheriff’s deputies to patrol it day and night for more than a year until we could transition it over to the National Park Service. We could not release that site because you had people who were always wanting to come onto the site for various reasons, to pay their respects. We didn’t feel that anyone should be on that site.”

Across the river from New York City, Hudson County, N.J. assembled three staging areas where EMS personnel treated injured people and transported them to hospitals. The county’s fire department responded on the day of the attacks, and several EMS personnel remained on the scene during recovery operations.

Arlington County, Va. EMS crews were first on site at the Pentagon, and by mid-morning more than 270 personnel were at work. Nearby counties contributed personnel and resources to the affected areas.

Counties bridged the gap staffing security at their airports between September 11 and when the Aviation Security Act established the Transportation Security Agency and put federal employees in charge of security and baggage screening at some county airports, which account for one-third of the nation’s airports, and a user fee funded security measures at all U.S. airports.

Santa Fe County, N.M. Commissioner Javier Gonzales came into the NACo presidency focusing on rural county development. In an instant, his leadership pivoted.

“We got him a place to speak in front of the National Press Club that December, and he did a great job presenting where counties were in terms of protecting the country,” said former NACo Legislative Director Ed Rosado.

Gonzales served as chairman of NACo’s Homeland Security Task Force and testified before the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee, Dec. 11, 2001, demanding better coordination from federal agencies and increased assistance to counties for preparedness and security. He called for a $3 billion local anti-terrorism block grant to help finance emergency preparedness investments and for adequate funding of local public health infrastructure under the Public Health Threats and Emergencies Act.

“Counties have a significant role to play in our new national strategy for homeland security,” Gonzales told the committee. “We are the public’s first defense, but we do have limited resources and will need additional support and cooperation from the federal government in order to succeed.”

NACo’s Homeland Security Task Force adopted a 16-point policy platform addressing top issues for county governments in the areas of public health, local law enforcement and intelligence sharing, infrastructure security and emergency planning and public safety.

County leader education and training

“I always saw NACo as a higher education for elected officials,” said C. Vernon Gray, a Howard County, Md. Councilmember who served as NACo president in 1999-2000. “It’s a place where you go and learn more. A lot of people become local officials because they’re popular at home. They get elected, and they’ve not done much in terms of educating themselves with all the issues.”

Gray himself was chair of the political science department at Morgan State University, so had a unique perspective on the issue.

NACo has always incorporated educational workshops into its programming. More and more, steering committee meetings include presentations by subject matter experts to help communicate complex issues to county officials who are otherwise trying to manage their counties, usually while working a full-time job at home.

Former President Bryan Desloge, a Leon County, Fla. commissioner, said NACo’s educational resources are important for smaller counties, where newly elected officials are more likely new to local government and need training that may not be available at home. Making county-focused education opportunities available to them, he said, can cut years off their learning curves and help prepare elected officials to govern effectively much faster than with experience alone.

In 2004, NACo introduced the County Leadership Institute (CLI) at New York University, later moved to Washington, D.C. The intensive leadership education course has served as an investment in county leaders, many of whom are in leadership roles in their state associations. Others would go on to NACo leadership and the presidency. Santa Barbara County, Calif. Supervisor Salud Carbajal later served in Congress.

Linn County, Iowa Supervisor Linda Langston, later a NACo president, was part of the inaugural CLI class. Participants to address the governing challenges one of their classmates was facing at home.

But Langston noted that a lot of the growth happened outside of class as the officials navigated New York City together.

“There were some people who had never been on the subway system and bonding over some of the experiences we had and things we saw along the way, built relationships that last to this day,” she said. “When we face challenges in our counties, a lot of times we’re consulting people who we got to know in that course.” NACo added training for rank-and-file county staff in 2019 with the development of the High Performance Leadership Academy. The 12-week online program was designed by former Secretary of State Colin Powell, who celebrated the partnership at the 20202 Legislative Conference.

The NACo Board invested $2.5 million in scholarships for county staff to participate in the academy, covering the cost for 2,000 graduates. An additional 8,000 county officials followed suit in the next few years.

Civic education

In 2011, NACo partnered with iCivics, a nonpartisan nonprofit founded by Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, to develop an interactive computer game that placed users in the shoes of a county official. Faced with a budget, a suite of county departments and a procession of constituents armed with requests for service, players learned the variety of responsibilities and powers county governments wield.

By matching their request to the appropriate department, players earned the confidence, and approval, of the voters to aid them in their quest for reelection. iCivics also offered a civic education curriculum focused on county government aimed at students from grades 6-12.

The online game Counties Work helped counties reach a complex target audience thanks to the wide variation in county authorities, and names, in different states.

“Your major textbook publishers aren’t going to put a chapter in a national civics or social studies textbook about county government because they’d have to change for every state,” said NACo President Glen Whitley, Tarrant County, Texas judge.

In 2022, NACo published “Governing on the Ground,” the story of county government seen through the eyes of 31 elected and appointed officials. These county leaders not only explained how their responsibilities and expertise in subjects like county roads, information technology, climate preparedness, mental health and homelessness interact with the public, they also offered a window into their motivations for pursuing a career in county government.

Related News

NACo Hosts County Leaders in Washington, D.C. and Launches We Are Counties National Public Affairs Advocacy Campaign

NACo is hosting nearly 2,000 county leaders from across the country for our annual Legislative Conference February 21-24.

NACo leaders urge new attendees to connect, engage at Legislative Conference

Nearly 300 first-time NACo Legislative Conference attendees heard from a slate of speakers welcoming them to the event and providing some guidance.

County News

Tumultuous ’80s test NACo’s fundamentals

NACo took two entrepreneurial risks in the 1980s — one nearly bankrupted the organization and the other has gone on to pay dividends for more than 40 years.