‘Stepping Up’ stakeholders step back to review progress

Key Takeaways

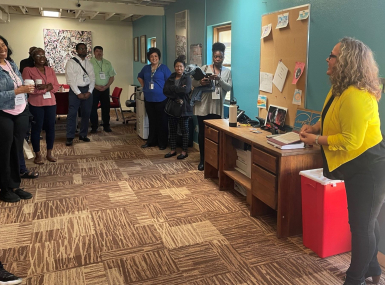

County officials and other stakeholders gathered May 31 in Washington to look back at the successes and continued challenges of the two-year-old Stepping Up program, a collaborative effort to keep the mentally ill out of county jails.

The initiative is a partnership between NACo, the Council of State Governments Justice Center and the American Psychiatric Association Foundation. Some 365 urban, suburban and rural counties have signed onto the program since it began, passing resolutions in areas that represent about 40 percent of the U.S. population.

Learn More

July 6 webinar: “Stepping Up: Conducting a Comprehensive Process Analysis and Inventory of Services for People with Mental Illnesses in Jails.”

“An estimated 2 million people with serious mental illnesses, almost three-quarters of whom have substance-abuse disorders, are booked into local jails each year,” NACo Executive Director Matt Chase told an audience gathered to hear a panel discussion.

Federal and state funding barriers, limited opportunities for local law enforcement training and no alternatives for arrests have created the epidemic across the country, Chase said. The result: County jails end up as de facto mental health hospitals. A bottom-up approach was launched two years ago to come up with solutions to the problem.

Stepping Up “is a young initiative that is really in service to a long-standing and old problem, as we know the crisis of people with mental illness in jails,” said Richard Cho, director, Behavioral Health Program, Council of State Governments Justice Center. “We don’t want to be here 20 years from now talking about this issue.”

“Collaboration is critical and shared expertise is what helped us start this initiative and is even more important as we continue and look at the critical work that is being done in this space,” said Dan Gillison, executive director, American Psychiatric Association Foundation.

USA Today reporter Kevin Johnson kicked off a panel discussion on the problem by looking back at a tragic story: Police came in contact with a computer contractor found to be mentally ill a month before he fatally shot nine people Sept. 16, 2013, at the Navy Yard in Washington, D.C. A month earlier, when police in Newport, R.I. were called to a hotel where he was staying, he complained that unidentified people were sending vibrations into his body, Johnson said. Since he had not committed a crime, police did what they could at the scene and later notified Naval authorities since he was in the Navy Reserve, but the warning was never forwarded to higher authorities, missing a possible opportunity to provide help for his mental illness, Johnson noted.

“What happened in Newport should be a wakeup call for all of us, because cases like this wash into the systems that you manage and confront you every day,” he said.

Several participants in Stepping Up from counties across the country talked about their experiences in a panel discussion.

Sheriff adds space for the mentally ill

Starting July 1, it will be illegal to lock up the mentally ill in jails in Colorado. San Miguel County, Colo. Sheriff Bill Masters, a Stepping Up panelist, said his jail in Telluride is adding a new wing for those suffering from substance abuse problems, which can often go hand in hand with mental illness.

The area is too remote, about 70 miles over “bad roads” to get to the nearest hospital, so in San Miguel County, anyone who is suffering from some sort of mental illness episode might be taken to the jail’s administrative areas, he said.

“We house our mentally ill even if they don’t commit a crime,” Masters said. “In winter time, it’s difficult to get people to the hospital and once you get there, there are no mental health beds. I’m the only 24-hour service in town with a warm bed for these people to stay in.”

Funding for a 24-hour triage center

A behavioral health leadership team in McLennan County, Texas, which includes the county seat of Waco, is looking at how to repurpose funding in order to get the best bang for their buck, said Tom Thomas, division director, Adult Mental Health Services, Heart of Texas Region Mental Health Mental Retardation Center.

The county created the Behavioral Health Leadership Team with community stakeholders including the mayor, county judge, county administrator, as well as the heads of local hospitals and a psychiatric facility and local foundations, he said. They were tasked with looking at short-term and long-term solutions for the community and trying to identify funding.

They started counting the number of people who had behavioral health histories that were being booked into the jail or taken to the ER each month; they found it averaged over 400 a month. The county sought out state funding and opened a 16-bed, 24-hour triage center for the mentally ill, instead of taking them to jail or the ER, where they faced an average wait time of 3.5 hours.

The number now being taken to jail or to the hospital is down to just over 100 per month. “We’re now not just talking about a return on investment, we’re talking about people here,” Thomas said.

Creating consistent plans in Maryland

“The Stepping Up initiative is extremely exciting to us,” said Kate Farinholt, executive director, National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), Maryland, who helped bring mental health courts and CIT (Crisis Intervention Team) to Baltimore City.

“In Maryland we are suburban, urban and rural,” she said. “Treating the mentally ill in Maryland is a patchwork…it’s not consistent. So, the Stepping Up initiative was extremely exciting to us. It will help create a consistent plan both for local and state level.”

“The value of Stepping Up is it brings all of the key roles together,” she said. “While telling our stories is transformational, having a judge or police chief come and explain why this is important is absolutely huge. It’s transformational. It changes the culture because it’s coming from within the culture.”

Also appearing on the panel May 31 were Councilman Michael Brown of Spartanburg County, S.C. and Altha Stewart, M.D., associate professor of psychiatry and director, Center for Health in Justice Involved Youth at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis.

She is also president-elect of the American Psychiatric Association. Stewart was featured in County News’ May 1 special issue of Hot Topics, “Breaking the Cycle,” about the move to divert the mentally ill from jail.

Featured Initiative

The Stepping Up Initiative

Stepping Up is a data-driven framework that assists counties through training, resources, and support that are tailored to local needs

Related News

Commission co-chairs discuss how counties can better treat mental health

Kathryn Barger and Dow Constantine have reflected on challenges and successes in Los Angeles County, Calif. and King County, Wash. to help guide the work of NACo’s Commission on Mental Health and Well-Being.

Bernalillo County empowers youth through community-based services

Bernalillo County, N.M.'s funding has allowed a drop-in center to cater to young people's needs while giving them an added sense of security.