Bernie Hilldenbrand's legacy, in and out of county government

Author

Upcoming Events

Related News

I've spent the last couple of weeks researching the life of my father intensely and penning his obituary. I knew him from the point of view of a daughter; his larger life, one whirling with adventure, unimaginable hardship, and wondrous, world-changing accomplishment, was only vaguely known to me before I burrowed into archives and unearthed the man in full. (Simply for length, I left out the Squeaky Fromme story, but will share it here one day soon.) His rise from a childhood of profound poverty and malnourishment to severely wounded soldier to the role of Washington power player and intimate of presidents is awe-inspiring. His wildly audacious one-man fight to save the Antietam Battlefield is almost movie-worthy. Many of you knew him from his comments on my threads here; even at 93, he was quickminded and absolutely hilarious. Please take a moment and read about him. The likes of my father will not be seen again.

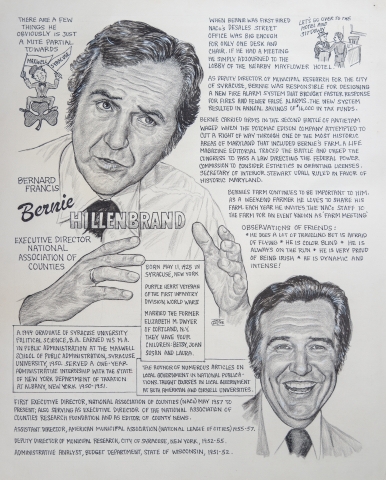

Bernard Hillenbrand, a decorated WWII veteran, Methodist minister, and longtime Executive Director of the National Association of Counties whose remarkable one-man campaign helped save the Antietam Battlefield area from power company development, died October 5 in Washington, DC. He was 93.

Learn More

Born in Syracuse in 1925, he was the son of Leonard Hillenbrand, a salesman for the Pittsburgh Paint and Glass Company, and his wife, Anne. With the advent of the Depression, Leonard lost his job and Model T, and was unable to find work for eight years. The family lived, Hillenbrand recalled, as “urban nomads” beside hobo jungles, at one point making ends meet by running a speakeasy from a basement, passing off pure alcohol mixed with sugar as “gin” and employing Bernard to make beer. Bernard, seriously malnourished, slept in a room so cold in winter that his fishbowl froze.

While in junior high, he learned that Manlius, an elite private high school, offered music scholarships. Believing that education could lead him out of poverty, he bought a French horn on credit. He couldn’t afford lessons, so he joined the orchestra and marching band and faked playing for the entire year. His teacher caught on; before the final concert, he took Hillenbrand aside and said, “Bernie, for God’s sake, don't blow in that horn tonight.” The scholarship was not to be, and Hillenbrand attended Syracuse’s public North High School.

He was sixteen, setting pins at a bowling alley, when he learned of Pearl Harbor. Eager to join up but too young for the Army, he attempted to enlist in the Merchant Marine, but failed the vision test. He tried the Royal Canadian Air Force, which admitted sixteen-year-olds, but his mother intercepted and destroyed their reply. He decided to stay in school and join the Army when he reached eighteen.

A superlative student, he graduated a semester early in January, 1943 with straight-As, the celebrated Rensselaer Medal for Excellence in Math and Science, and no money for college. Soon after, while watching a building fire at Syracuse University, he chatted with a bystander. The man happened to be Dean of Admissions Eric Faigle, and offered Hillenbrand a full scholarship. Hillenbrand enrolled the next morning.

On his eighteenth birthday, Hillenbrand joined the Army, winding up in the European Theater’s First Infantry Division. In November, 1944, during a ferocious artillery barrage at the Battle of Hürtgen Forest, he was blown from his foxhole and knocked unconscious. He woke in a huge pool of blood-drenched snow, his hand mangled. While stumbling toward an aid station, he heard a shell coming. He and another soldier dove for a depression in the snow simultaneously, and the soldier landed on top just as the shell exploded. The soldier was blown up, but his body partially shielded Hillenbrand, saving his life. Seriously wounded in the head, back, shoulder, and hand, Hillenbrand was hospitalized for a year and a half. Once released, he visited the family of the man whose death had saved him.

In 1946, Hillenbrand rejoined Syracuse University, and in 1949, graduated cum laude with a degree in political science. He then hitchhiked to California to work as a deckhand on a Swedish ship. Traversing the Panama Canal, he learned he’d won a full scholarship to Syracuse’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. He returned home, and in 1951, completed a master’s degree in public administration.

After working for the governments of Wisconsin and New York State, he became Syracuse’s Deputy Director of Municipal Research. In 1955, he married the former Elizabeth Dwyer, a journalist at the Syracuse Herald-Journal. They moved to Washington, DC, where Hillenbrand became Assistant Director of the American Municipal Association, now the League of Cities.

In 1957, he became the first executive director, and the only full-time employee, of the fledgling National Association of Counties (NACo). With only a telephone, chair, and desk, he opened shop in an abandoned laundry room across from the Mayflower Hotel. The room was barely larger than his desk, so when he arranged meetings, he crossed the street to impress his guests in the hotel’s opulent lobby.

Over twenty-five years, Hillenbrand built NACo from an obscure laundry room operation to one of America’s largest and most powerful public interest groups. Described by one newspaper as “one of the shrewdest, toughest operatives that Congress and the White House have to deal with,” he worked with six presidents and was so respected that during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, he was summoned to the Pentagon and asked to coordinate contact between federal and local governments in the event of nuclear war.

In 1967, his tenacity proved decisive in a landmark, headline-making conflict. That spring, without notifying local officials or the public, Potomac Edison power company laid plans to run 500,000-volt power lines, strung from 110-foot towers built on a 200-foot right of way, across the C&O Canal and alongside Maryland’s perfectly preserved, bucolically beautiful Antietam Battlefield. An ardent student of Civil War history, Hillenbrand owned a 150-year-old farm adjacent to Antietam, with a farmhouse that served as a hospital during the battle. Walking his farm with his son, Hillenbrand found flagged stakes, the calling cards of PE surveyors. He was, his son wrote, “quietly furious.”

PE had the right of eminent domain, and neither the local nor the federal governments could halt the plan. But Hillenbrand found a loophole. The Department of the Interior, under Secretary Stewart Udall, had jurisdiction over the C&O Canal. If he could rally support and encourage Udall to block PE from crossing the canal, Hillenbrand might be able to protect the battlefield.

He began by publishing an open letter to the head of PE. For the public and local officials, it was the first news of PE’s plans. He made impassioned presentations before county and state legislatures, decrying what he saw as the disastrous impact of PE’s plan and urging legislators to contact Udall. He recruited historians and public officials and mailed out information kits for the public, politicians, media, and historical organizations. He bought one share of PE stock, then showed up at a stockholder’s meeting to lobby for his cause. He even bought a giant red balloon to demonstrate how high the towers would be. He’d set off what was called “the Second Battle of Antietam.”

PE fought for its plan and sued Hillenbrand for the right to build across his farm. But Hillenbrand had stirred up what one paper called a “national storm of protest.” His lobbying of the National Trust for Historic Preservation led the organization to publicly oppose PE. Prominent publications backed his cause, and LIFE ran an editorial on the urgent need to save Antietam. Udall was swayed, and blocked PE from running lines across the C&O Canal. PE ultimately found an alternate route, and Antietam remained pristine. Hillenbrand’s souvenir of victory was a surveyor stake, which he kept in a shadow box in his farmhouse.

Divorced in the 1970s, Hillenbrand married Aliceann Wohlbruck, the Executive Director of the National Association of Development Organizations, in 1979. They remained married until her death in March, 2018.

In 1982, Hillenbrand retired from NACo and in 1986, earned his masters of divinity from Wesley Theological Seminary. He worked as chaplain-intern at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, associate pastor at Washington’s Mt. Vernon Place United Methodist Church, pastor at Maryland’s Cedar Lane United Methodist Church, director of Chevy Chase Community Ministries, and outreach coordinator for the Interfaith Conference of Metropolitan Washington. From 1995-1997, he was the county and faith outreach advisor to Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Henry Cisneros. Until his death, he worked with Wednesday Clergy Fellowship, a minister’s group that addresses social concerns in the African-American community.

“There are a lot of people in Washington who get paid as lobbyists, and there are some people who are lobbyists, but there are very few whose representation rises genuinely to the level of public service,” Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan said in 1982. “Bernie Hillenbrand is one of those men.”

Hillenbrand is survived by his children – Lisa, John, Susan, and Laura – two stepchildren, six grandchildren, and a sister. He will be interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

Attachments

Related News

Now I know I can adapt my communication style

San Juan County, N.M. Commissioner Terri Fortner spent her career working with people one-on-one, but she overcame hangups about online communication when the pandemic forced her onto video calls when she first took office.

County service meets a veteran’s need for purpose in Spotsylvania County, Virginia

After Drew Mullins transitioned from a high-performance lifestyle in the military, he found the environment and purpose he sought when he took office in his county.

Now I know that solid waste is complicated

Custer County, Idaho Commissioner Will Naillon says solid waste removal is "one of the things that people often take for granted until it’s their job to make sure it happens... that’s the story of being a county commissioner."