NACo-NSA Joint Task Force Report: Addressing the Federal Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy

Upcoming Events

Related News

The Social Security Act, Sec. 1905(a)(A) prohibits the use of federal funds and services, such as Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Medicare and Medicaid, for medical care provided to “inmates of a public institution.” While this language was intended to prevent state governments from shifting the health care costs of convicted prison inmates to federal health and disability programs, it has an unintended impact on local jail detainees who are in a pre-trial status and have not been convicted of a crime.

|

https://www.youtube.com/embed/KrMiJ8XUsVA How the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion is Impacting Local Justice Systems |

|

“As a nation, we have abandoned the health care needs of our most vulnerable residents. By making 911 a hotline for those in need of mental health services, we send people experiencing a behavioral health crisis to jail at a time when we should instead be providing them with resources and care in the community. We are assured better health outcomes when the burden of care is not placed on local law enforcement.” Commissioner Mary Ann Borgeson |

The language makes no distinction between:

Jails vs. Prisons

Counties serve as the entry point to the criminal justice system. Jails were designed for short-term stays mainly for those pending disposition or sentencing, as well as for those convicted of lower level crimes such as misdemeanors. Nationally, local jails admit nearly 11 million individuals each year. Today, our local jails are being used increasingly to house those individuals with mental health, substance abuse and/or chronic health conditions.

Pre-trial Detainees vs. Convicted Inmates

- Pre-trial detainees: are being held while they await trial and have not been convicted of a crime; primarily housed in county jails.

- Convicted inmates: have been convicted of committing serious offenses; primarily housed in state and federal prisons.

The current federal policy denies federal health benefits to individuals who are pending disposition, and still presumed innocent under the U.S. Constitution:

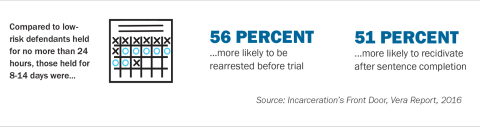

The current federal policy of terminating or suspending the federal health care coverage for these individuals results in poorer health outcomes, ultimately driving up recidivism (re-arrest) rates and overall taxpayer costs. At present, access to federal health benefits is based on the location where you are awaiting due process in the pre-trial phase.

Those Who Post Bail:

- Await process in the community and retain eligibility of federal benefits

Those Who Do Not Post Bail:

- Await trial in a local jail and lose access and coverage to health benefits

- Are often the most vulnerable and in need of treatment for behavioral, mental health and chronic illnesses

|

About the Task ForceCo-Chair: Hon. Nancy Sharpe, Commissioner Co-Chair: Hon. Greg Champagne, Sheriff

|

Letter from Task Force Co-Chairs

The U.S. Constitution is clear: individuals are presumed innocent until proven guilty. Despite this clear constitutional mandate, people who receive federal health benefits, such as Medicaid, Medicare or CHIP benefits for juveniles are stripped of those benefits when arrested and jailed for an alleged crime, before conviction. From that starting point comes this report by a joint task force of the National Association of Counties (NACo) and the National Sheriffs’ Association (NSA).

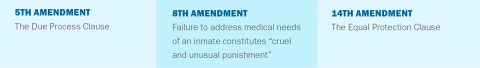

The Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy (MIEP), which denies or revokes federal health and other benefits, is a violation of the equal protection and due process clauses of the Fifth and 14th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution, respectively. This policy also places undue financial and administrative burdens on local jails and produces unfavorable health outcomes for individuals and communities. By contrast, the uninterrupted provision of health care helps our residents break the cycle of recidivism exacerbated by untreated physical and mental illnesses and substance use disorders.

To address the challenges posed by the MIEP, NACo and NSA formed a joint task force representing county leaders, law enforcement, judges, prosecutors, public defenders, behavioral health experts and veterans’ service providers. Over the past year, the joint task force explored the impacts of this federal policy and its contribution to the national behavioral and mental health crisis, and rates of recidivism in our nation’s jails.

As detailed in this report, data on local justice systems show counties nationwide face an increasing number of pre-trial detainees and inmates experiencing mental health complications, often with co-occurring substance use disorders. Local jails serve as one-stop treatment centers for individuals with these illnesses. Without adequate community resources, jails have become de facto behavioral health hospitals and treatment facilities.

Access to federal health benefits for non-convicted individuals would allow for improved coordination of care, while at the same time decreasing short-term costs to local taxpayers and long-term expenses to the federal government. Cost savings that could be invested to improve post-release care coordination would decrease crime, reduce recidivism and greatly contribute to the overall health and safety of our constituents. Through the recommendations in this report, the members of the joint task force hope to demonstrate that improving care coordination across federal, state and local governments can alleviate the strain that the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy has placed on our local criminal justice systems, our counties and most importantly, our residents.

|

Section 1: Recommendations for Government Entities

As we call on county governments and local criminal justice systems to lead efforts to provide better continuity of care and reduce recidivism for justice-involved individuals in our communities, we recognize that these local efforts will be far more effective when carried out in partnership with state and federal counterparts. The following recommendations call for state and federal actions that would complement local efforts.

Recommendations for Federal Policy Makers

Amend Section 1905(a)(A) of the Social Security Act to allow for the continuation of federal benefits such as Medicaid, Medicare and Children’s Health Insurance Plan for pre-trial detainees. The language in Section 1905(a)(A) of the Social Security Act should only apply to post- adjudicated individuals who have gone through due process. Federal policy makers should clarify that amending Section 1905(a)(A) of the Social Security Act allows the continuation of federal benefits, such as Medicaid, Medicare and Children’s Health Insurance Program, for those enrolled and eligible individuals who are pending disposition in local jails, especially those individuals suffering from mental health, substance abuse and/or other chronic health illnesses. The continuation of these benefits aligns with an individual’s U.S. Constitutional rights to due process and equal protection under the Fifth and 14th Amendments.

A Note on Bail ReformMembers of this Task Force acknowledge the role of bail on the prevalence of pre-trial detainees in our local jails and cannot overlook bail reform as a recommendation for improving local justice systems. While the parallels between bail reform and the rights of the pre-trial detainee to health care are evident, this report focuses exclusively on strategies and recommendations that are directly related to addressing the federal Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy and its unintended consequences on our local systems and residents. |

Provide national guidance and set best practices for data collection in the local criminal justice system. The lack of aggregate data on jail health care needs and costs has been a barrier to estimating total jail health care expenditures and has contributed to the persistent lack of fiscal resources for local jail systems. The U.S. Department of Justice should set national standards on data collection for local justice systems and jail health care services that will allow local, state and federal entities to adequately address the needs of these facilities.

Develop budget-neutral regulations that promote accessible behavioral health services and care continuity. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services should update and provide guidance on regulations that would assist in the coordination of behavioral health services that do not shift costs onto local governments and entities. Specifically, the agency should update rules that govern the confidentiality of substance use disorder patient records under 42 CFR Part 2 to enhance coordination between health care providers and behavioral health specialists.

Under current 42 CFR Part 2 rules, when a person is identified as having a substance abuse disorder, no information, even confirmation that the person is being treated, may be released without a written authorization by the client or guardian. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy rule, on the other hand, permits the disclosure of health information needed for patient care and other important purposes (i.e., coordination of care, consultation between providers and referrals). Lack of congruence between these two standards will lead to continued confusion over what can be shared and by whom. Moreover, patients are likely to face increased safety risks when providers are not able to access their complete records.

The Task Force encourages HHS to take steps to fully align Part 2 requirements with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) to further harmonize privacy provisions to protect individuals with substance abuse disorders so counties can continue to make advancements toward ending the substance use disorder crisis.

Case Study: Justice-Involved Veterans Initiative in Dakota County, Minn.In 2018, Dakota County, Minn. established the Justice-Involved Veterans (JIV) program to improve service delivery to veterans involved with the county’s criminal justice system. The program is an integrated service delivery model that was created to not only identify the unique issues faced by veterans in the criminal justice system, but existing systems they interact with and services needed that are not currently available. Through collaboration with the community corrections department, the sheriff’s office and the veterans services department, the program creates a network of care that addresses the underlying behavioral health and other issues that lead veterans into the criminal justice system |

Set best practices and incentivize the sharing of health records, especially as it pertains to behavioral health data. The federal government should support the integration of health information technologies into the local health care delivery system, including the behavioral health and substance use treatment systems and county jail health systems. The use of a range of information technologies will help facilitate appropriate access to health records and improve the standard of care available to patients, while protecting privacy. This includes deployment of broadband technologies to the widest possible geographic footprint. Other tools facilitate evidence-based decision-making and e-prescribing. Using broadband technologies, telemedicine applications enable real-time clinical care for geographically distant patients and providers.

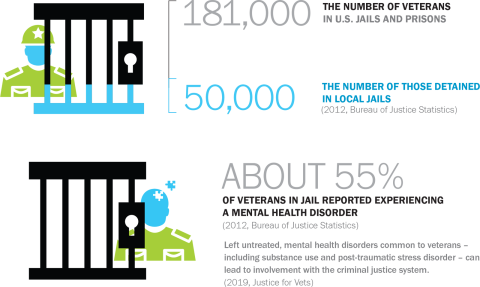

Create partnerships between the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and counties to enhance access to and continuity of care for veterans in local justice systems. The federal government should expand programs that help connect justice-involved veterans with benefits they have earned through the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The department’s Veterans Justice Outreach (VJO) program, for instance, funds 314 VJO specialists across the country, who have served more than 180,000 justice-involved veterans since the creation of the program in 2009. Programs such as the VJO help identify veterans when they are processed into local jails, thereby allowing jail health administrators to better meet the unique health needs of these individuals, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or a substance use disorder.

Expand veteran treatment courts to help justice-involved veterans rehabilitate and avoid recidivism. Veterans treatment courts allow communities to serve justice-involved veterans in a way that is specifically tailored to the needs and experiences of veterans. For example, veterans treatment courts are uniquely capable of dealing with issues such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and the judges overseeing these courts are more familiar with the VA, state Veterans Affairs departments, locally based veteran service organizations and other veteran-specific resources that may be outside of the justice system but can still help a veteran rehabilitate and avoid recidivism.

Snapshot: Health Care Access Issues for Veterans in Our Local Justice Systems

Veterans who are arrested do not forfeit their eligibility for medical care. However, under federal regulation 38 CFR § 17.38 (c)(5), the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs is prevented from providing hospital and outpatient care to a veteran while they are incarcerated in a local jail.

|

|

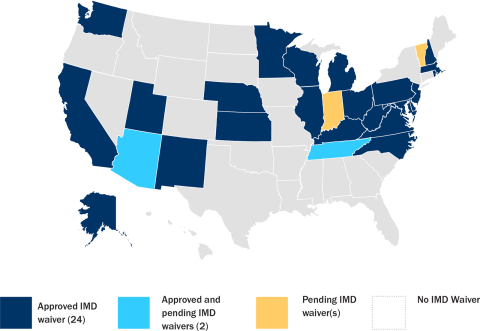

Recommendations for State Governments

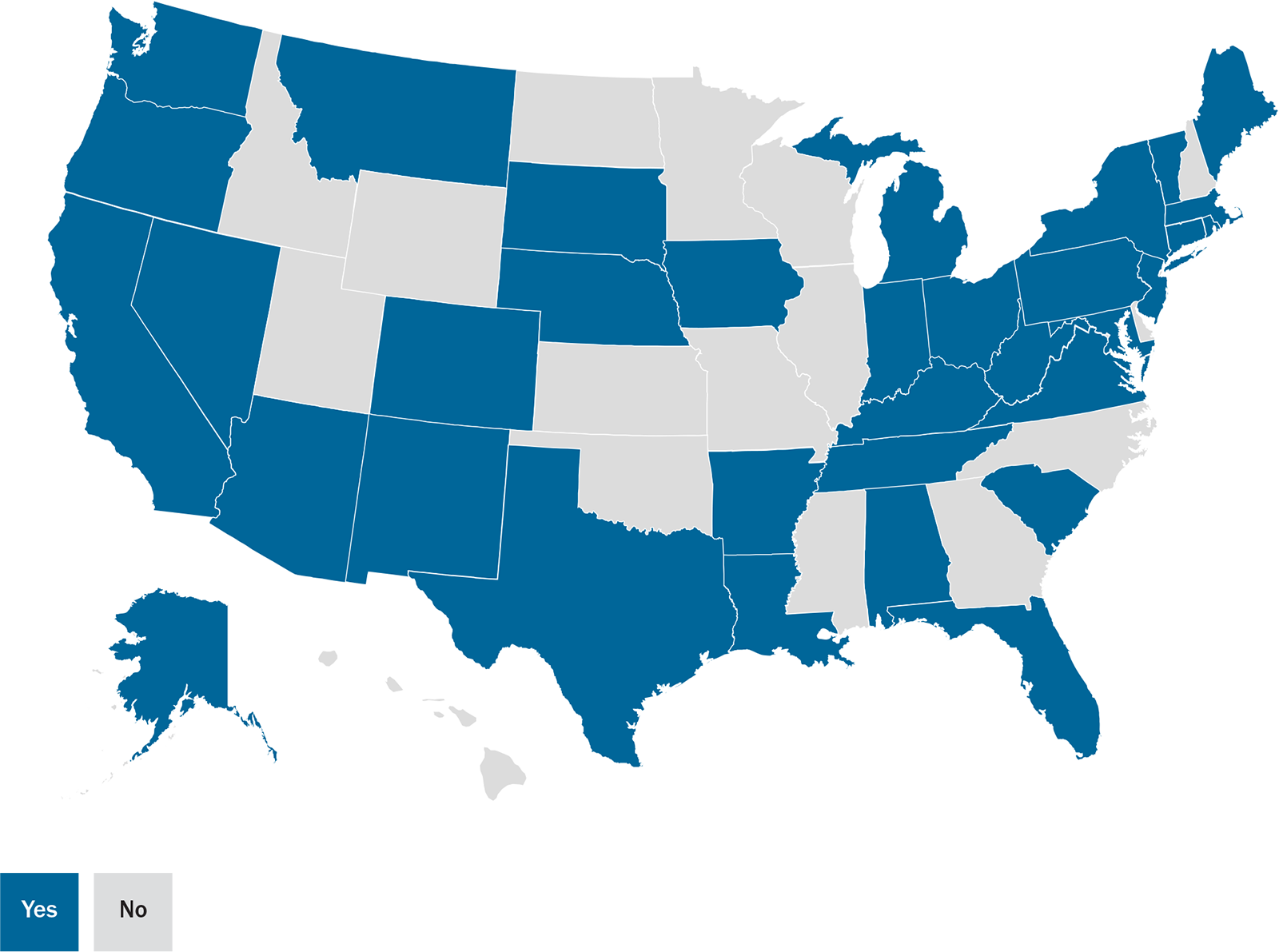

Apply for an IMD Exclusion waiver. In 2018, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) set a new waiver policy that would waive the institutions for mental diseases (IMD) exclusion, a section of the Medicaid law within the Social Security Act that prohibits the use of federal Medicaid funding for most inpatient psychiatric services. HHS now considers and approves Medicaid demonstration waivers covering short-term stays for acute care provided in psychiatric hospitals or residential treatment centers. As of July 2019, 24 states were approved for IMD exclusion waivers allowing them to receive federal Medicaid funds for Substance Use Disorder (SUD) services in IMDs, and one state had an approved waiver for mental health services. Increased flexibility around the IMD exclusion will increase capacity to provide adequate mental and behavioral health treatment services in the community.

Approved and pending section 1115 medicaid imd payment waivers, as of OCT. 30, 2019

Notes: IMD= Institution for Mental Diseases. “Approved and pending IMD waiver” refers to approved substance use disorder waiver and pending mental health IMD waiver. “Pending IMD waiver” refers to SUD and/or mental health IMD waiver. While this task force supports the amendment of federal policy that preserves pre-trial detainee rights to federal health benefits, in the interim we are supportive of suspending, rather than completely terminating these benefits.

Source: KFF, Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Waivers with Behavioral Health Provisions (Oct. 30, 2019).

“More than 95 percent of prisoners eventually return to the community, bringing their health conditions with them.”

Suspend – instead of terminating -- Medicaid benefits for pre-trial detainees. To avoid violating the MIEP, states have typically terminated Medicaid enrollment when a pre-trial detainee is brought to jail. When this occurs, it can take months for an individual’s Medicaid benefits to be reinstated after release. This interrupts access to needed medical, mental health and additional treatment when an individual reenters the community. The coverage gap caused by terminating Medicaid coverage can lead to increased recidivism. To address this, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has issued guidance strongly recommending that states suspend, not terminate, Medicaid while individuals are detained in jail.

States Reporting Corrections-Related Medicaid Enrollment Policies in Place for Prisons or Jails: Medicaid Eligibility Suspended

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation’s State Health Facts

Many States Mandate Counties Provide Some Level of Health Care for Low-Income, Uninsured or Underinsured Residents

Since being signed into law in 1965, the Medicaid program has helped counties provide a safety net for those who are unable to afford medical care. The program creates increased access to health care services for low-income residents, which improves their health, productivity and quality of life. Medicaid also reduces the frequency of uncompensated care provided by local hospitals and health centers to low-income and uninsured residents and lessens the strain on county budgets.

|

According to the Commonwealth Fund (2019), states that have expanded Medicaid have achieved major cost savings by moving eligible adults into Medicaid expansion coverage. Medicaid expansion also allows states to reduce spending on uncompensated health care costs as uninsured individuals gain coverage. For instance, in Montana, Medicaid expansion saved the state more than $25 million and offset the state’s expansion costs in FY 2017. Source: Hayes, S.L., Coleman, A., Collins, S. and Nuzum, R. (2019) The Fiscal Case for Medicaid Expansion |

3. Expand Medicaid. Covering over 70 million individuals, Medicaid is the country’s largest program providing health coverage and health care services to the nation’s low-income population. The Affordable Care Act of 2010 gives states the option to expand Medicaid coverage to low-income adults without children. This population disproportionately comprises the jail population, who without Medicaid are often uninsured or underinsured. This population is also disproportionately impacted by behavioral, mental and chronic illnesses that follow them back into their communities once they are released. Medicaid is the largest source of funding for behavioral health services in the United States and a vital source of health coverage for individuals with substance use disorders. The expansion of Medicaid will help counties provide better care for the justice-involved individuals in our communities by qualifying them for health care that will increase access to necessary treatment and reduce their risk of recidivism.

|

Section 2: Pre-Trial Detainees and Jail Health Care

Overview of Pre-Trial Populations

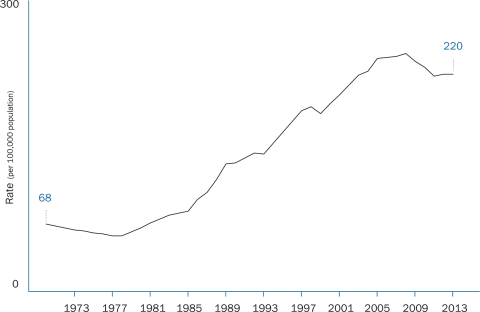

There are an alarming number of individuals in pre-trial status detained in our local jails. On any given day, nearly half a million people who have been charged, but not convicted of a crime, are detained in local jails– often for months at a time- while they await trial. Approximately 11 million people cycle in and out of local jails each year, according to the Pre-Trial Justice Institute, with six out of 10 of those individuals being pre-trial detainees; a number that has experienced tremendous growth in the past few decades.

The Vera Institute of Justice reports that from 1970 to 2015, the number of individuals detained before trial increased an astounding 433 percent (Vera, 2019). This population also accounts for 95 percent of all jail population growth since the start of the new millennium (Pre-trial Justice Institute, 2019).

National pre-trial incarcertaion rate

Data/chart from vera report: out of sight, June 2017

Source: Jacob Kang-Brown and Ram Subramanian. Out of Sight: The Growth of Jails in Rural America.

New York: Vera Institute of Justice, 2017.

An Intimate Look at Pre-Trial Detainees

Upon arrest, the decision to detain an individual is made by the court in a pre-trial release hearing. During that hearing, a judge rules on whether to release the individual and whether any conditions, such as bail, should be set for that release (The Hamilton Project, 2018). Pre-trial detainees are comprised of two distinct populations: those who have been remanded by a judge because they have been found to be a danger to the community or pose the risk of failing to appear at trial and those who are detained purely on the inability to afford bail.

Studies show that individuals who are detained pre-trial are more likely to be of lower socio-economic status. Pre-trial detention disproportionally impacts those of low-income status and homeless individuals, who, despite having committed a minor offense and permitted by a judge to await trial outside of jail, must remain confined because they lack the resources to post bail. Research finds that the median pre-arrest income of inmates held on bail is approximately $16,000 a year, in contrast to a median annual income of $33,000 for non-incarcerated individuals (The Hamilton Project, 2018). A report on Philadelphia and Miami area metropolitan counties reveals that the typical defendant earned less than $7,000 in the year prior to arrest, and over 50 percent of defendants were unable to post bail set at $5,000 or less. In a group of New York counties, nearly half of all defendants charged with misdemeanors who were held for longer than a week had bail set at $1,000 or less (The Hamilton Project, 2018). Even when bail was set at $500 or less, 40 percent of people remained in jail until their cases were adjudicated (Vera, 2019).

The majority of individuals unable to meet bail fall within the poorest third of society (Prison Policy, 2016) and are more likely to qualify for or be enrolled in social services and federal assistance programs like Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and housing assistance.

Pre-trial detainees are also disproportionately people of color. Blacks and Latinos represent 50 percent of the total pre-trial detainee jail population and are more likely to be held due to their inability to pay monetary bail. Data indicates that the average black man, black woman and hispanic woman in local jails who is unable to post a bail bond, lived below the poverty line before incarceration (Prison Policy, 2016).

While the number of juvenile offenders in jails has decreased nationwide, the percentage of those being held in local facilities has increased. All 50 states authorize pre-trial detention for youth under age 18, although practices for detaining juveniles vary within states and by county (National Juvenile Defender Center, 2019). From 1997 to 2017, the number of juvenile offenders decreased by 56 percent. During that same period, the percentage of juvenile offenders held in local facilities increased by 7.5 percent while the percentage of those held in state facilities decreased by 12.1 percent (BJS, 2017).

Rates of youth with mental disorders within the juvenile justice system are consistently higher than those within the general population of adolescents, with over 70 percent of the 2 million youth arrested in the U.S. every year having a mental health condition. There is growing reliance on local correctional facilities to provide necessary treatment for our youth, however continued and additional treatment services upon release are necessary as re-arrest rates are as high as 75 percent within three years after confinement (Mental Illness and Juvenile Offenders, 2016).

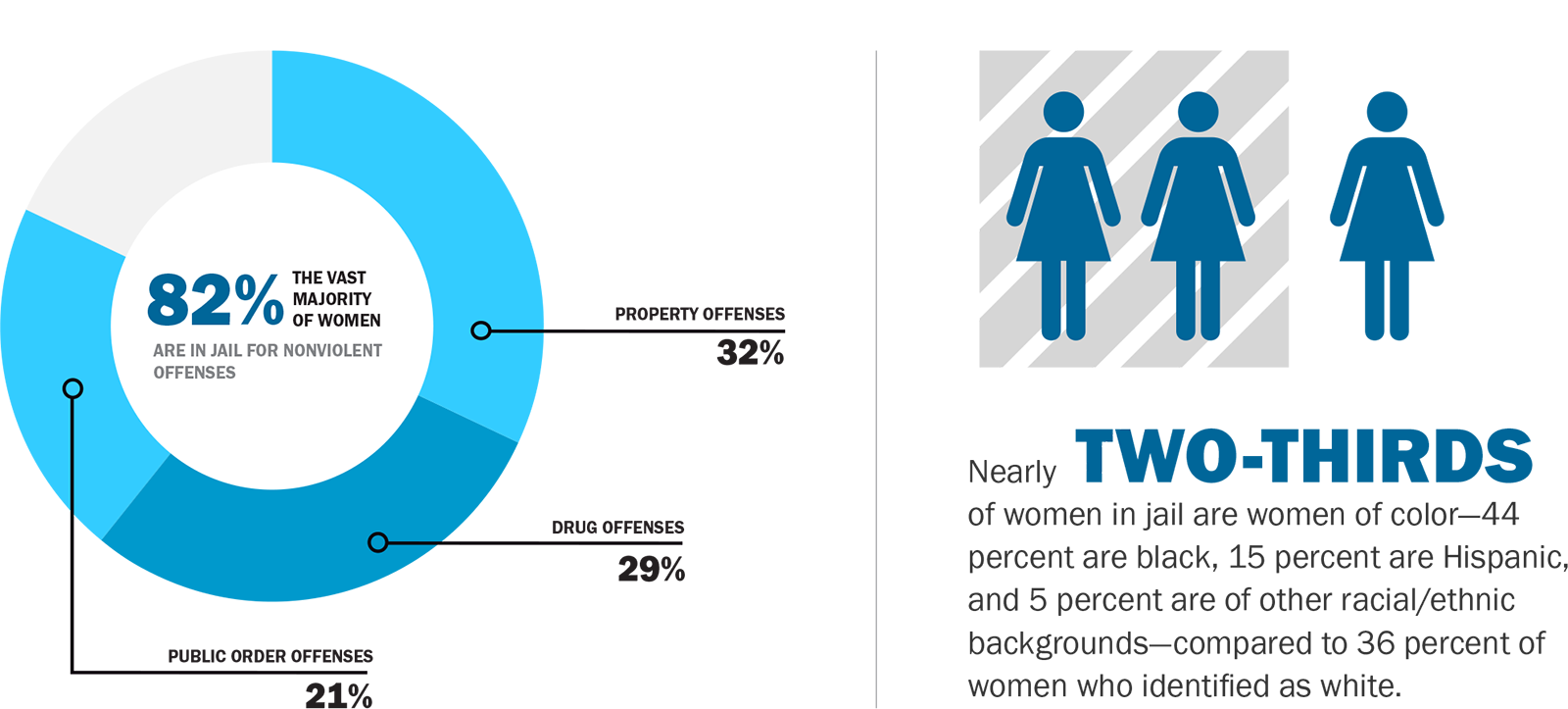

Source: Vera Institute, 2015. “Misuse of Jail In America”

Women are more likely to be detained because they cannot post bail and the number of women being held in jails is growing rapidly. The number of women in local jails nationwide now accounts for approximately half of all women incarcerated, increasing 14-fold in just under 50 years (Vera, 2016). In stark contrast from years past, today women are held in jails in every county across the U.S.

Despite being denied release less often than men and often having lower bail amounts set, women are less likely to be able to afford bail when it is set (Vera Institute, 2019). In 2012, over 75 percent of women in pre-trial detainee status in Massachusetts were held on bail amounts less than $2,000, with an average length of stay from 60 to 77 days.

Many pre-trial individuals are being detained for felony charges, however the length of stay can be substantial for those who cannot afford bail. In New York City between 2009 and 2013, 12 percent of defendants in misdemeanor cases and 43 percent of defendants in felony cases were detained (The Hamilton Project, 2018). Individuals who have been charged with misdemeanors are typically considered a low public safety risk and yet are often detained because they cannot afford bail. Seventy-five percent of both pre-trial and sentenced individuals are in jail for non-violent traffic, property, drug or public order offenses (NACo, 2019).

The amount of time that an individual is detained if they cannot afford bail can be substantial, often ranging from 50 to 200 days. The median duration of stay on felony crimes can be from 54 to 250 days for driving-related felonies (The Hamilton Project, 2018).

Percentage of population affected with serious mental illness

Source: Incarceration’s Front Door: The Misuse of Jail in America. New York, NY: Vera Institute of Justice, 2015

The pre-trial detainee population has unique health challenges. The Urban Institute found that pre-trial detainees entering Connecticut jails who were on Medicaid had greater health needs than those who were not. Their health needs ranged from medical, mental health, substance abuse and co-occurring mental health and substance abuse treatment needs (Urban Institute, 2016).

The elevated behavioral and mental health needs of this population make jail detainees more likely to be in some kind of crisis and has resulted in higher rates of suicides in jails, and increased vulnerability to harm (University of Pennsylvania Law School, 2013). Additionally, the transiency of the pre-trial detainee’s stay in local jails makes the continuity of health care services critical for the safety of the individual and the surrounding community.

|

Profile of Health Care Needs in Local Jails

Local correctional health systems vary widely across the country, with factors such as county size, budget and inmate demographics shaping counties’ delivery systems.

While some larger counties may opt to provide on-site care through employed medical staff and specialized treatment facilities, smaller counties may provide medical care or they may partner with local health departments or another county agency to deliver care. In other cases, counties may contract health services to private or non-profit vendors. For counties contracting with these vendors, payment models and type of health care services provided can vary. Counties must also assess other factors such as the type of medical personnel needed to ensure the health and well-being of detainees.

| 40 Percent |

of jail inmates have a chronic medical condition |

| 44 Percent |

of jail inmates have been diagnosed by a professional as having a mental health disorder |

| 63 Percent |

of jail inmates have a substance use disorder |

In assessing jail health needs, counties are responding to complex medical conditions among inmates. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics and the National Institutes of Health, compared to the general population, individuals in jails suffer from higher rates of mental illness, behavioral health conditions and higher rates of serious chronic conditions.

In addition to these complex medical conditions, local jail populations far exceed the populations of federal and state prisons. Together, these factors have created financial and administrative challenges for sheriffs, jail health administrators and local county budgets.

To address these challenges, federal and state action is needed to promote accessible behavioral health services and care continuity for pre-trial inmates. At the federal level, Congress and federal agencies should support the integration of health information technologies into the local health care delivery system, including the behavioral health and substance use treatment systems and county jail health systems. At the state level, state legislators and agencies should pursue waiver options to expand the reach of mental and behavioral health services to more individuals and consider Medicaid expansion to include low-income adults without children.

How Health Care is Administered in the Jails

While some larger counties can afford to provide on-site care through employed medical staff and specialized treatment facilities, smaller counties may partner with a local hospital, health department or other county agency to deliver care to detainees. In other cases, counties contract with private vendors to provide health services to inmates. Within these arrangements, payment models and the type of health care services provided can vary depending on a jail’s daily intake and medical care required by the detainees.

|

Employed medical staff Contractor model Partner county agency |

How Health Care is Administered in the Jails

While some larger counties can afford to provide on-site care through employed medical staff and specialized treatment facilities, smaller counties may partner with a local hospital, health department or other county agency to deliver care to detainees. In other cases, counties contract with private vendors to provide health services to inmates. Within these arrangements, payment models and the type of health care services provided can vary depending on a jail’s daily intake and medical care required by the detainees.

| Payment Model | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

No Risk Sharing |

||

|

Hourly |

The county pays a contractor an hourly rate for providing care in the facility. |

In its 2014 request, Midland County, Mich. (ADP*:250), asked bidders to propose hourly rates for nurses, an office assistant and a physician. |

|

Fee for service |

The contractor is paid for staffing and the services provided. |

St. Mary’s County, Md. (ADP: 239), specified that the bidders must submit pricing per service, per month including 24/7 nursing coverage and the cost of a physician or physician assistant conducting all necessary sick call visits. |

Risk sharing |

||

|

Flat fee |

The contractor receives a fixed annual fee, often paid in monthly installments, for providing care. The fee amount may be set to cover costs such as labs and hospitalization, or the county may be responsible for paying for these services directly. |

In Aiken County, S.C. (ADP: 345), bidders were asked to propose an annual fee for providing health care services. The proposed price was to include off-site and diagnostic services, among other necessary care. |

|

Capitated |

The contractor receives a set amount per person held in the jail per day. This fee may cover costs such as labs and medications, or the county may retain financial responsibility for such services. If the county is responsible for some services, financial risk to the vendor is reduced. |

In Volusia County, Fla. (ADP: 1,417), the winning vendor was to be paid based on the previous month’s ADP. The capitated price would include materials, supplies and off-site services, including specialist visits and labs. |

*Average daily population (ADP) is the average number of people incarcerated in a jail on a daily basis. All ADPs are drawn from the Request for Proposals (RFP) examined.

Source: Pew analysis of RFPs

“Although jails are constitutionally mandated under the Eighth Amendment to provide health care to detainees, counties fulfill these requirements in different ways and play a major role in shaping local correctional health systems (Pew Charitable Trusts, 2018).”

Paying for Health Care in Jails

HIV/Hepatitis C Treatment“In 2009, New York enacted a law that requires the New York Department of Health to conduct annual reviews of HIV and Hepatitis C care in state and local correctional facilities. Since this law was enacted, county jails in New York have been required to provide more extensive testing to inmates for HIV and Hepatitis C, and more instances of these diseases have been discovered, and subsequently required expensive treatment. The type of treatment inmates receive is up to the discretion of a medical professional. Within the last 10 years, new drugs for treating Hepatitis C have been approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) with an estimated cost of $90,000 for the 12-week treatment. For many counties, the cost of providing such treatment to inmates causes great financial strain to jail medical budgets. Furthermore, once an individual begins treatment on this medication, he or she must continue the full course of treatment for it to be effective, which requires jail officials to monitor and maintain an inmate’s treatment record and required doses over a period of time which may precede or follow their incarceration.” NYSAC News magazine, Spring/Sumer 2018 “Health Costs and Concerns for Local Jails” |

The Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy shifts the full cost of health care services for pre-trial, incarcerated individuals to local taxpayers — as opposed to the traditional federal, state and local government partnership in financing and delivering safety-net services.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, local communities spent $22.2 billion on jails in 2011. However, this figure underestimates the actual dollar amount communities invest in our local justice systems, since other local government agencies help finance jail costs not shown in jail budgets, including health care services (Vera Institute of Justice, 2015).

Case studies on the price of county jails indicate that local correctional health costs can vary widely between counties depending on the daily population and health needs of detainees. Prescription drug costs are a high cost-driver in local jails. According to a 2017 Texas Association of Counties report, between 2011 and 2017, the cost of providing prescription medications for jail inmates and detainees increased by more than 20 percent. HIV medications, for instance, can cost thousands of dollars each month. Providing this medication and other special treatments can be cost-prohibitive for county jails, where inmates and detainees are more likely than the general population to be infected with HIV. For detainees struggling with substance use disorders, providing specialty drugs such as naloxone can also pose cost challenges for county jails.

The state does not reimburse counties for housing inmates awaiting trial on felony charges. Pre-trial detention does directly affect the finances of local government and households. (The Sycamore Institute, 2018)

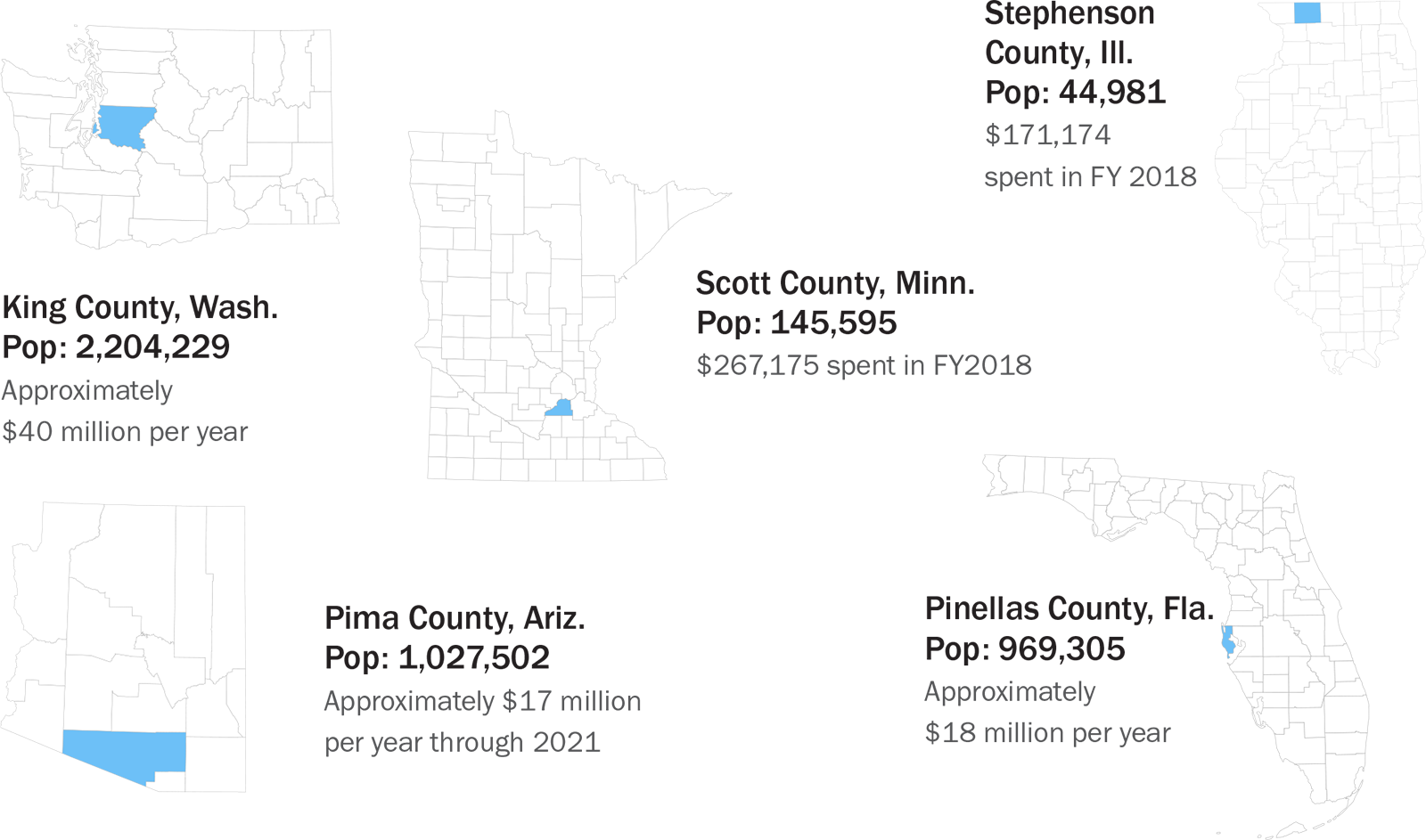

Jail Health Care Expenditures By County

|

Pima County, Ariz. |

Pinellas County, Fla. |

King County, Wash. |

Stephenson County, Ill. |

Scott County, Minn. |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total Jail Population |

1,896 |

2,923 |

2,854 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Average Daily Population |

1,912 |

2,788 |

2,084 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Estimated Average Time in Jail (Days) |

5.3 |

7.7 |

5.7 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Rated Jail Capacity (Percent) |

91% |

95% |

76% |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Total County Expenditures (2017) |

$943,198,000 |

$1,252,425,000 |

$3,464,948,000 |

$27,280,000 |

$147,151,000 |

|

Total Health Expenditures (2017) |

$70,588,000 |

$184,915,000 |

$612,823,000 |

$9,254,000 |

$3,414,000 |

Post-Release Outcomes

Monterey County, Calif.:“A study found that inmates from the county jail who received treatment for behavioral health disorders after release spent an average of 51.74 fewer days in jail per year than those who did not receive treatment” Providing Health Care Coverage for Former Inmates, National Conference of State Legislatures 2014 |

When an individual suffering from a behavioral, mental or substance abuse issue is released from jail back into the local community, providing health services immediately upon release is vital. However, because access to federal health benefits is rarely immediately restored upon release, individuals enter the community without access to much-needed health care. The process of reenrollment can be lengthy, often taking upwards of 90 days (“Applying for Medicaid,” 2017). With little to no continuity of care services being provided, these individuals will often fall into old habits and end up back in jail.

Further, family members who also rely on those benefits are also placed at risk due to the prolonged interruption of funding.

This cycle of recidivism presents a serious problem, which counties have the responsibility of addressing. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, only about four percent of the nearly 11 million individuals detained in jail each year are given a prison sentence, leaving 96 percent of jail detainees and inmates returning into the community at some point.

Individuals detained pre-trial who are released back into the community are 32 percent more likely to commit another crime upon release due to the disruption of care provided for mental, behavioral or substance abuse issues (Heaton, Mayson and Stevenson, 2017).

Ensuring that health care treatment continues post-release is an important strategy in reducing rates of local jail recidivism. Innovative approaches to ensure that an individual has access to the necessary care and treatment immediately upon release from jail can lead to better outcomes for justice-involved individuals.

Riverside County, Calif. has developed a “Whole Person Care” (WPC) program, which seeks to provide links to services for individuals coming out of incarceration. Riverside County is the fourth most populous county in California with more than 2 million people and operates five jails within its jurisdiction. The county recognized a need for increased care coordination between jails and the community in order to assist with such a high volume of individuals moving in and out of the jail system.

The county found that about half of all individuals released back into the community on probation returned to court within the first year as a result of substance or alcohol abuse. Without the access to proper care and treatment due to the loss of their federal health benefits, these individuals were unable to reintegrate completely into society. The county sought to address this issue by creating their WPC program, which has seen tremendous success in providing continuity of care services.

San Bernardino County, Calif. addresses recidivismThe Sheriff’s Transitional Assistance Reentry Team (START) program is designed to reduce recidivism among inmates who are prone to reoffend. START is available to inmates across the social spectrum including veterans, those who are homeless, medically frail subjects and those with mental or behavioral health issues. The program’s focus is to connect participants with resources and services while they are still in custody, so they have a support system in place once they are released. Since the program’s inception in 2019, START has connected 817 inmates with services and resources. |

The program, which received funding from the state of California, allowed the county to hire an expansive network of nurses, housing specialists, case managers and social services coordinators to assist in inmate reentry efforts. The county implemented a screening process that identifies the individual’s needs for continued mental health, medical, substance use, health insurance coverage and other supportive services. From this screening, a transition plan is developed to provide the individual with the best possible chance of integrating back into the community.

With the assistance of multiple regional partners from within the county and surrounding areas, the county has seen a drastic reduction in re-incarceration of this vulnerable population and increased numbers of individuals who are able to reenroll in their health benefits. This has been attributed to the prescreening process, which allows for individuals to find proper channels to begin the process of reenrollment. Additionally, Riverside County has seen an increase in information sharing and willingness to collaborate among regional partners because of this program (Nightingale, 2019).

While the Riverside County WPC program focused on probationers, tracking such an increase in the number of pre-trial detainees enrolled in active health care is extremely difficult due to a high number of individuals cycling through county jails each year. However, with better data tracking and data sharing techniques, WPC programs like the one implemented in Riverside County provide a viable model for pre-trial detainees to be linked with the proper health care services they may need.

Early reenrollment for federal health benefits is essential. Another component to decreasing the likelihood of recidivism is to have the individual reenrolled in their federal health benefits as soon as possible following release. States that have enacted policies to suspend rather than terminate federal health benefits upon arrest are able to reenroll individuals faster and more efficiently which leads to better health outcomes and lower rates of recidivism.

However, states like Wisconsin which terminates Medicaid, also known as BadgerCare, for people upon arrest, have seen increased recidivism rates for individuals unable to get proper treatment for substance abuse, mental and behavioral health issues post-release. In these circumstances, counties must step in to help minimize the time someone is without health coverage after leaving jail.

Dane County, Wis. through funding from the AmeriCorps program, hired a BadgerCare outreach specialist who meets with pre-trial and convicted inmates to evaluate their health insurance needs. Each evaluation allows for insight into particular needs an individual may have following release and can help to identify specific services and contacts for any substance abuse or mental health service needs.

Increasing awareness of behavioral, mental and substance abuse disorders upon arrest can lead to better care coordination upon release. Being able to properly identify signs and symptoms of a behavioral, mental health or substance abuse issue during the booking process can drastically improve the post release outcomes for justice-involved individuals.

Johnson County, Iowa implemented the Jail Alternatives Program which works to improve service delivery and access for individuals entering the justice system who suffer from any behavioral or mental health issues. This is implemented through a prescreening process upon booking into jail that includes a questionnaire about current or previous mental health or substance abuse disorders, medication and treatment. Jail Alternatives Coordinators use these questionnaires to identify potential “clients” and work to assess symptoms of the individual and determine treatment needs.

Upon release, these individuals are linked with a community network of hospitals, mental health and substance abuse treatment providers, advocacy groups, local veterans administrations, homeless services providers and peer groups. This allows for individuals to enter the community with access to the health services they desperately need and promotes public safety and community wellness (NACo, 2016).

Providing access to these federal health benefits for those awaiting trial would greatly assist communities in breaking this cycle of recidivism caused by continued lack of access to treatment for mental illnesses and/or substance abuse disorders.

While Riverside, Dane and Johnson Counties show the ability of county governments to step in and provide transitional service to individuals leaving jail, not all counties have the capacity or funding to provide these exceptional services. In these cases, stripping federal health benefits of non-convicted individuals is unconstitutional and leaves county jails to serve as de facto behavioral mental health facilities within the community. Without access to proper health benefits, individuals continue to cycle through the local criminal justice system at a short-term and long-term cost to both local taxpayers and the federal government.

By providing a direct path to reenroll in their health benefits, individuals returning to society would be able to maintain a continuum of care that will improve health outcomes, make them less likely to commit another crime landing them back in jail and improve public safety.

|

Section 3: Best Practices in Jail Health Care & Strengthening the Care Continuum

Jails across the nation are faced with many obstacles when providing health care to detainees, including funding constraints, workforce shortages and limited opportunities for training and development. This report identifies best practices for strengthening the provision of health care for justice-involved individuals by strengthening community partnerships, identifying individuals with health care needs, creating linkages to health service providers and leveraging public sector grant funding. In addition to providing counties with information on actionable best practices, this report also highlights innovative practices that counties across the country have implemented to improve justice and health care outcomes.

Best Practices for Local Governments

1. Use data collection and information sharing to identify those in need of health services

In each county, there is a population of justice-involved individuals with complex health and social needs that are difficult to meet without coordinating services and supports across systems and providers. Integrating health information with information from other systems is one way to improve treatment and services for this population. However, accessing, using and sharing health data is often a significant barrier to advancing streamlined solutions that deliver effective interventions and improve the outcomes of the targeted population.

Bexar County, Texas(2017 Population: 1.9 million) The Bexar County Sheriff’s Office, San Antonio Police Department and all other law enforcement agencies in Bexar County have implemented procedures to help divert individuals suffering from mental illness away from criminal justice involvement and into treatment and care. They accomplish this by instructing officers to administer and document the Law Enforcement Screening Questionnaire (known as LE4) prior to submitting the required booking slip. The booking slips are then provided to a pre-trial assessment officer for review as the detainee proceeds through the booking process. The LE4 consists of four questions that function as an initial screen administered by the arresting officer. Its purpose is to flag persons who may have a mental health issue. The LE4 tool is the initial step of the intake process at magistration. Based on the individual’s responses, they may be referred to more in-depth assessments, which are completed by a licensed mental health professional. The most direct benefit from the LE4 questionnaire for Bexar County is the ability to identify early signs of mental illness so that the person can be further evaluated and appropriately processed, avoiding unnecessary jail. Over the first five months in which the LE4 was used, 626 individuals were identified as needing further assessment, according to the Bexar County Mental Health Department. Of those, 505 were referred to a clinician based on the follow-up assessment results. |

Counties that utilize data to support diversion begin by developing and implementing plans to combine data across organizational silos to identify the highest utilizers of multiple services and their needs. Once data sharing agreements and plans are implemented, counties have implemented pre-arrest diversion strategies that offer alternatives to incarceration for individuals with mental health and substance use disorders. Pre-arrest strategies often include tools for first responders to determine whether an alternative to arrest and potential incarceration in the criminal justice system is appropriate and, if appropriate, to link individuals to treatment and services. The goal of a successful pre-arrest diversion strategy for a high-utilizer population is to reduce the rates of emergency health and public safety service usage, while increasing linkages across health, behavioral health, housing and other social supports so that an individual receives the services they need. Such a strategy aims to improve the health and wellbeing of individuals while promoting better public safety outcomes and a more efficient use of public resources (NACo, 2016).

2. Establish community support programs

Building County Justice and Health Partnerships

Building community support and collaboration is a critical first step in creating successful strategies and initiatives to serve justice-involved populations. Improving health care in the justice system requires strong relationships among a diverse set of people, including law enforcement, behavioral health providers, housing and homelessness services, faith-based organizations, advocates, people with lived experience and other community service providers.

The foundation of successful communication and engagement strategies begins with a leadership team that creates a clear mission statement outlining the county’s intentions and sharing this with the broader community.

A convening of major stakeholders or a community town hall-style event is a great starting place. A community leader such as a police chief, mayor, county commissioner, sheriff or judge can use convening power to bring all relevant parties together and help establish a shared vision. Counties have also focused on identifying individuals from each group that should be involved, such as law enforcement, homeless services, children services, behavioral health providers and hospitals.

County court systems are well positioned to facilitate collaboration between local leaders from the justice and health systems and state agencies with responsibility for correctional and public health. Through a planning process, partners can implement pilot projects that address continuity of care between the jail and community and on integrating Medicaid-managed care into services accessed through the courts.

Tulsa County, Okla. (2017 Population: 646,266)The City of Tulsa Municipal Special Services Docket connects individuals with mental illnesses, co-occurring substance use disorders and/or experiences of homelessness to behavioral health services, employment and housing providers over a period of six months. Upon completion of the docket, charges, fees and fines are dismissed. Peers play a critical role in the operation of the docket, as they are enlisted to conduct initial screenings, provide ongoing navigation and attend monthly court hearings with clients for emotional support. The court docket serves about 150 individuals annually. Tulsa County also provides Programs of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) as an evidence-based service delivery model providing intensive, outreach-oriented mental health services for people with the most severe mental illnesses. Using a 24/7 team approach, PACT delivers comprehensive community treatment, rehabilitation and support services to clients in their homes, at work and in community settings. Building community supports such as PACT and other non-traditional programs of care allows an individual, who otherwise may be subjected to multiple hospital visits or jail, the ability to address the demands of their illness while remaining in the community. The program is intended to assist clients with basic needs, increase compliance with medication regimens, address any co-occurring substance abuse treatment needs, help clients train for and find employment and improve their ability to live with independence and dignity. Peers assist with guidance to PACT staff on how to provide courteous, helpful and respectful services to clients during intake. Currently, there are three PACT teams in Tulsa. |

3. Leverage federal grant funding

Spending on correctional health care has increased significantly in the past two decades. Nationwide, jails spend two to three times more on detainees requiring mental health care than detainees without those needs. Research has shown that holding individuals who are experiencing mental illness inside jails is more expensive than treating them in the community. In Wayne County, Mich. housing a mentally ill individual in jail costs about $31,000 a year, but the same person could receive treatment in the community for $10,000 a year, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Substance Use Disorder Treatment Grants

The Department of Justice, Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the Department of Health and Human Services provide grant funding that can supplement local and state financial resources spent on local jail health care. In the past few years, the federal government has increased grant funding to help meet rising critical mental health and substance use disorder treatment needs in communities.

DOJ has a long history of providing technical and financial assistance to counties for substance use disorder and mental health treatment services for justice-involved individuals. The Residential Substance Use Disorder Treatment for State Prisoners (RSAT) Program (U.S. Department of Justice, 2019) provides funding for the development and implementation of treatment programs in state, local and tribal correctional and detention facilities. Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) is an allowable cost under this program. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) defines MAT as the use of medications in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies for the treatment of substance use disorders. SAMSHA recognizes MAT as an effective treatment for individuals working to overcome substance use disorders. All RSAT grants are awarded to state administering agencies that sub-grant these funds to correctional agencies across their respective states.

U.S. Departments of Justice and Heath and Human Services also provide grant opportunities including the Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Site-based Program (U.S. Department of Justice, 2018), the Opioid Affected Youth Initiative (U.S. Department of Justice, 2018) and the Rural Communities Opioid Response Program (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018), among others.

Many of these grant programs support MAT and residential and non-residential treatment.

Coffey County, Kan.(2017 Population: 8,266) With funding from a grant obtained by the Central Kansas Mental Health Center, counselors in Coffey County visit county jail inmates on a weekly basis, including inmates whose mental health issues may not have been evident at booking but who are struggling with being incarcerated. Kansas passed legislation in 2006 that allows jails to bill inmates’ private insurance and the Coffey County Jail does so whenever possible. The jail also contracts with an organization that provides health care to underserved populations across the country in many settings, including jails, to adjust medical bills down to the Medicaid rate. |

Mental Health Treatment Grants

Two grant programs that provide support for costs associated with providing treatment for those with mental health disorders in jail are the Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program (JMHCP) (U.S. Department of Justice, 2019) and the Improving Reentry for Adults with Co-occurring Substance Abuse and Mental Illness program (Department of Justice, 2018).

JMHCP supports cross-system collaboration to improve response and outcomes for individuals with mental illness or co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorder who come into contact with the criminal justice system. The program provides financial and technical assistance to local government efforts to leverage social services and other partnerships that will enhance and increase law enforcement responses to individuals with mental health and substance use disorder treatment needs.

The focus of the Improving Reentry for Adults with Co-occurring Substance Abuse and Mental Illness Program is to provide standardized screening and assessment, collaborative comprehensive case management, and pre- and post-release programming that address criminogenic risk and needs, including mental illness and substance use disorder.

Federal Grant Program |

Program Purpose |

Comprehensive Opioid, Stimulant and Substance Abuse Sitebased Program (COAP) |

Program PurposeProvide financial and technical assistance to states, units of local government and Indian tribal governments to plan, develop and implement comprehensive efforts to identify, respond to, treat and support those impacted by the substance abuse epidemic Eligible Funding Activities

Funding AdministrationBureau of Justice Assistance, U.S. Department of Justice |

Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program (JMHCP) |

Program PurposeProvides financial and technical assistance to facilitate collaborations among criminal justice, mental health and substance abuse treatment systems Eligible Funding ActivitiesActivities to increase access to mental health and other treatment services for individuals with mental illness or co-occurring mental illness and substance abuse issues. Funding Administration Bureau of Justice Assistance, U.S. Department of Justice

|

Opioid Affected Youth Initiative |

Program PurposeProvides funding and technical assistance for states, local governments and tribal jurisdictions to develop cross sector collaboration, data collection and analysis and implementation of services for youth impacted by opioid abuse Eligible Funding Activities

Funding AdministrationOffice of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, U.S. Department of Justice |

Rural Communities Opioid Response Program (RCORP) |

Program PurposeProvides funding for multi-sector consortia to enhance their ability to implement and sustain substance use disorder prevention, treatment and recovery services in underserved rural areas Eligible Funding Activities

Funding AdministrationHealth Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

Telehealth Grants

State, local and tribal correctional agencies are increasingly utilizing telemedicine to reduce inmate health care costs and provide specialized services to those incarcerated in remote areas of the country.

Implementing a telehealth program can involve significant costs due to the equipment, network management and broadband expansion required. Federal grants that provide support for local correctional telemedicine and telehealth programs include the USDA’s Community Connect (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2019) grants and the Distance Learning & Telemedicine (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2019) grants.

Community Connect Grants help fund broadband deployment in rural communities where it is not yet economically viable for private sector providers to deliver service. Funding can be used for construction, acquisition or leasing of facilities, spectrum, land or buildings used to deploy broadband service.

Distancing Learning and Telemedicine grants help rural communities use the unique capabilities of telecommunications to address the opioid epidemic through prevention, treatment and recovery.

Correctional Facility Modification Grants

Addressing the medical needs of jail populations may require facility modifications for constructing medical units, specialized testing and treatment or mental health housing. The USDA offers the Community Facilities Direct Loan & Grant Program (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2019), which funds both medical facilities and public safety facilities including prisons and jails. This program provides financial assistance to meet the financial needs associated with renovation or construction.

Best Practices for Local Justice Systems

1. Maximize Opportunities for Diversion

As a part of a holistic approach to building community safety nets, developing a strong community health system could have a positive impact on the number of people in jail. For example, one study found that on average, a 10 percent increase in public mental health inpatient spending led to a 1.5 percent decline in jail populations (Yoon and Luck, 2016).

Counties that focus on communication and engagement with agencies such as health, social services, law enforcement and the courts have experienced an effect that motivates and nurtures holistic community actions to improve overall provision of mental health and substance use disorder treatment services, as well as general health services to populations in need.

It is beneficial to understand and integrate the perspectives of individuals with mental illnesses and substance use disorders and those who have experienced homelessness into the community health care planning and improvement process.

A robust and coordinated community health network can provide the foundation for law enforcement and first responders to divert individuals in crisis, who in different circumstances would become incarcerated, or otherwise justice-involved. Law enforcement and other first responders need a place and trained staff for warm handoffs of individuals in crisis. A warm handoff approach involves the primary care provider, in this case county jails, facilitating a face-to-face introduction of the patient, or inmate, to behavioral health specialists who will provide care upon the individual’s release from jail. These are key elements of successful diversion programs and ensure that individuals are directly and immediately connected to treatment services. While some communities already have facilities that can accommodate drop-off treatment, stabilization and referral, others may have to build new capacity to facilitate warm handoffs (NACo, 2016).

Cook County, Ill.(2017 Population: 5.21 million) Through the support of The Chicago Community Trust, Treatment Alternatives for Safe Communities (TASC) facilitated a health reform strategy and implementation process on behalf of Cook County Criminal Courts, to bring together leaders from the justice and health systems and state agencies with responsibility for health reform implementation. TASC managed a planning process that created a platform for health and justice partners to identify problems, solutions and new ideas regarding healthcare reform. Through the process, partners implemented pilot projects, including the process for pre-trial detainees to receive application assistance to CountyCare, a Cook County Medicaid Health Plan. Additional strategies focus on addressing continuity of care between jail and community and on integrating Medicaid managed care into services accessed through the courts. Fulfilling this constitutional responsibility is expensive. In Cook County, the Health and Hospitals System spent nearly $100 million providing jail health care in fiscal year 2016 for 6,072 inmates ($16,500 per inmate)—more than seven times what the county spent on traditional public health services. Cook County Health & Hospitals System, “FY 2017 Proposed Budget and Financial Plan” (2016), http://www.cookcountyhhs.org/wpcontent/uploads/2016/08/CCHHS-FY2017-Preliminary-Budget-08-19-16.pdf. |

2. Leverage Peer Support for Mental and Behavioral Health Treatment Inside and Outside of Jail

According to SAMHSA, “a peer provider (e.g. a certified peer specialist, peer support specialist or recovery coach) is a person who uses his or her lived experience of recovery from mental illness and/or addiction, and skills learned in formal training, to deliver services in behavioral health settings to promote mind-body recovery and resiliency.” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019).

Peers have been recipients of substance use disorder, mental health and co-occurring services and are willing to use and share their personal and practical experience to benefit both treatment teams and clients. Once trained and certified, a peer can specialize in a particular population.

3. Use Telemedicine to Improve Access and Decrease Costs

The application of telehealth services allows patients, physicians and nursing staff to communicate through secure audio and video technology for real time clinical consultations. Corrections systems are using telehealth to improve access to specialty care, in areas such as mental health, substance use disorder, behavioral health and chronic care management. This option has been proven to save time and money spent on arranging transport, staffing and providing security at hospitals and clinics. Jails can also access care more quickly. This often leads to better care management and medication adherence resulting in improved outcomes (Wicklund, 2017).

Some correctional systems used telehealth as early as the 1980s and its use has dramatically increased with the arrival of improved technology and electronic medical records, as well as pressure to control rising medical costs. According to the Pew Charitable Trusts, telehealth has cut inmate health care costs by nearly half in the Texas, which now spends just $3,805 per prisoner annually compared to the national average of $6,047 (Ollove, 2016).

In addition to the cost savings, telehealth services help ensure that inmates and detainees can access the medical care that they need. Inmate advocates caution that telehealth should not be used excessively and in-person medical consultations should be used when appropriate.

|

Section 4: Legal Implications and Recommendations at a Glance

Jails Have a Duty to Provide Medical Care to Their Justice-Involved Populations

In the 1976 landmark decision, Estelle v. Gamble 429 U.S. 97 (1976), the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that access to health care is a constitutional right for incarcerated individuals. In essence, the Court held that jails and prisons are constitutionally mandated to provide medical care for all inmates. The ruling added that an inmate must rely on authorities to treat their medical needs and if the authorities fail to do so, those needs will not be met. The ruling added that an inmate must rely on authorities to treat their medical needs; if the authorities fail to do so, those needs will not be met.

“…deliberate indifference to serious medical needs of prisoners constitutes the ’unnecessary and wanton infliction of pain,’ proscribed by the Eighth Amendment. This is true whether the indifference is manifested by …doctors in their response to the prisoner's needs or by {officers} intentionally denying or delaying access to medical care or intentionally interfering with the treatment once prescribed.

Under the ruling, jail professionals cannot be deliberately indifferent to an inmate’s medical needs. The case established the principle that the deliberate indifference to address the medical needs of an inmate by authorities constitutes “cruel and unusual punishment,” as prohibited by the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Implications

While federal cases such as Estelle v. Gamble, Wilson v. Seiter 501 U.S. (1991), Helling v. McKinney 509 U.S. 25 (1993), and Farmer v. Brennan 511 U.S. 825 (1996) address access to medical care, conditions of confinement, the potential for liability for future harm and the overall duty to protect, there are other core constitutional clauses that raise questions about current interpretation and practice of federal policy. For example, 42 U.S.C. 1396d §1905(a)(A) of the Social Security Act prohibits federal payments for the cost of any services provided to an “inmate of a public institution,” except when the individual is a “patient in a medical institution.” This single provision results in counties covering the full cost of health care services for pre-trial detainees who would otherwise be eligible for coverage under the MIEP.

Congress and the federal government must address the legal implications of the federal Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy on a pre-trial detainees’ ability to gain access to their eligible federal benefits while incarcerated.

County officials recognize the obligation to provide medical care for jail inmates: “where” the individual is receiving the medical care (i.e. community, jail, hospital) should be irrelevant as to the availability of the federal benefits. As currently written, the availability of the benefits is premised on location and status, lacking a legitimate governmental purpose and arguably, disparate in application. Congress and the federal government must address the legal implications of the federal Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy on a pre-trial detainees’ ability to gain access to their eligible federal benefits while incarcerated. One way this can be accomplished is by amending the administrative interpretation of the Social Security Act, so that the language only applies to those who are post-adjudication.

Denying Federal Benefits to Pre-Trial Detainees, as Prohibited by the MIEP, Violates the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and 14th Amendments.

The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution holds that “No person shall…be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law…” The 14th Amendment guarantees that no state shall “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The federal Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy creates a complete failure to distinguish individuals in pre-trial status awaiting disposition of their criminal charges from individuals who have been adjudicated and convicted of a crime. Pre-trial detainees are presumed innocent – they have not been convicted of a crime, are awaiting their due process and all protections under the Fifth and 14th Amendments remain in place.

However, the MIEP policy makes no distinctions between those presumed innocent and those convicted. To deny a presumed innocent individual their eligible federal Medicaid, Medicare, CHIP or VA benefits, without due process of law, is a violation of their constitutional rights. As such, the MIEP should be amended to address this issue.

“The Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution holds that “No person shall... be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law”

The Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy creates a double standard as it treats similarly situated pre-trial detainees differently, in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, which provides “nor shall any State [...] deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. The Equal Protection Clause guarantees that distinctions cannot be drawn between individuals solely on decisions that are arbitrary and that lack any legitimate governmental objective. And yet, the MIEP, by its very language, treats similarly situated pre-trial detainees differently. A pre-trial detainee, pending disposition, who is released back into the community either by posting bail and/or is given community supervision remains eligible for federal benefits. The pre-trial detainee, pending disposition, who is unable to post bail and/or is denied community supervision, is ineligible for their federal benefits. This disparate treatment of similarly situated pre-trial detainees is exactly what the Fifth and 14th Amendments protect against.

The MIEP must be amended to allow pre-trial detainees access to their eligible federal benefits and to prevent any potential constitutional infringements.

|

|

References

“Justice Denied: The Harmful and Lasting Effects of Pre-trial Detention.” 2019, Vera Institute of Justice, https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/Justice-Denied-Evidence-Brief.pdf. Accessed Dec. 2019.

“Why We Need Pre-trial Reform.” 2019, Pre-trial Justice Institute, https://www.pre-trial.org/get-involved/learn-more/why-we-need-pre-trial-reform/. Accessed Nov. 2019.

“The Economics of Bail and Pre-trial Detention.” 2018, The Hamilton Project, https://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/BailFineReform_EA_121818_6PM.pdf. Accessed Nov. 2019.

“Detaining the Poor: How Money Bail Perpetuates an Endless Cycle of Poverty and Jail Time.” 2016, Prison Policy Initiative, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/incomejails.html. Accessed Nov. 2019.

“Overlooked: Women and Jails in an Era of Reform.” 2016, Vera Institute of Justice, www.safetyandjusticechallenge.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/overlooked-women-in-jails-report-web.pdf. Accessed Dec. 2019

“Detention.” 2019, National Juvenile Defender Center, https://njdc.info/practice-policy-resources/topical-issues/detention/. Accessed Dec. 2019.

“Annual Survey of Jails: Jail-Level Data.” 2017, U.S. Dept. of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=dcdetail&iid=261. Accessed Nov. 2019.

“Federal Policy Impacts on County Jail Inmate Health Care & Recidivism: How Flawed Federal Policy is Driving Higher Recidivism Rates.” 2019, National Association of Counties, https://www.naco.org/sites/default/files/documents/Medicaid%20and%20County%20Jails%20Presentation.pdf. Accessed Nov. 2019.

“Using Jail to Enroll Low-Income Men in Medicaid.” 2016, The Urban Institute, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/86666/using_jail_to_enroll_low_income_men_in_medicaid.pdf. Accessed Dec. 2019.

“The Conditions of Pre-trial Detention.” 2013, University of Pennsylvania Law School, https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2182&context=faculty_scholarship. Accessed Dec. 2019.

“Pre-Trial Detention in Tennessee.” 2019, The Sycamore Institute, https://www.sycamoreinstitutetn.org/pre-trial-detention/. Accessed Dec. 2019.

“Jails: Inadvertent Health Care Providers.” 2018, Pew Charitable Trusts, https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2018/01/sfh_jails_inadvertent_health_care_providers.pdf. Accessed Nov. 2019.

“The Price of Jails: Measuring the Taxpayer Cost of Local Incarceration.” 2015, Vera Institute of Justice, https://www.vera.org/publications/the-price-of-jails-measuring-the-taxpayer-cost-of-local-incarceration. Accessed Nov. 2019.

“Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Site-based Program: FY 2018 Competitive Grant Announcement Notice of Funding.” Bureau of Justice Assistance. 2018. https://www.bja.gov/funding/COAP18.pdf. Accessed Nov. 12, 2019.

Office of Justice Programs: Residential Substance Abuse Treatment for State Prisoners Program. —. n.d. https://www.bja.gov/ProgramDetails.aspx?Program_ID=79. Accessed Nov. 12, 2019.

“Data-Driven Justice: Using and Sharing Data.” National Association of Counties. 2019. https://www.naco.org/resources/index/using-and-sharing-data. Accessed Nov. 17, 2019.

“Jails: Inadvertent Health Care Providers.” Pew Chartitable Trusts. 2018.

“Data Driven Justice Playbook: How to Develop a System of Diversion.” National Association of Counties. 2016.

SAMSHA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions. 2019. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/workforce/team-members/peer-providers. Accessed Nov. 15, 2019.

“Applying for Medicaid – Long Term Care Information.” 2017, Long Term Care.gov, https://longtermcare.acl.gov/medicare-medicaid-more/medicaid/applying-for-medicaid.html. Accessed Dec. 2019.

“Increase Funding for the Second Chance Act.” 2019, National Association of Counties, https://www.naco.org/resources/increase-funding-second-chance-act-sca. Accessed Dec. 2019.

“The Downstream Consequences of Misdemeanor Pre-trial Detention.” 2017, Stanford Law Review, https://www.stanfordlawreview.org/print/article/the-downstream-consequences-of-misdemeanor-pre-trial-detention/. Accessed Dec. 2019.

“Coordination of Care in the Justice Involved Population.” 2019, Riverside University Health System, https://naco.sharefile.com/d-s329652e0a2d46308. Accessed Dec. 2019.

“Dane County serves as model for recidivism task force.” 2019, Associated Press, http://www.startribune.com/dane-county-serves-as-model-for-recidivism-task-force/510151502/. Accessed Dec. 2019.

“Health Coverage and Care for the Adult Criminal Justice-Involved Population. Kaiser Family Foundation” 2014. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/health-coverage-and-care-for-the-adult-criminal-justice-involved-population/. Accessed Dec. 2019.

U.S. Department of Justice (2017). “Indicators of Mental Health Problems Reported by Prisoners and Jail Inmates.” Retrieved from: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/imhprpji1112.pdf. Accessed Dec. 2019.

The Cost of County Government: 2016 Unfunded Mandates Survey. Texas Association of Counties (2017). Retrieved from: https://www.county.org/TAC/media/TACMedia/Legislative/Unfunded_Mandates_Complete_Book.pdf. Accessed Dec. 2019.

National Association of Counties, Data-Driven Justice Playbook: How to Develop a System of Diversion, Version 1.0, Dec. 2016

Underwood, L. A., & Washington, A. (2016). Mental Illness and Juvenile Offenders. International journal of environmental research and public health, 13(2), 228. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4772248/. Accessed Jan. 2020.