Shining a light on agrivoltaics

Counties across the country are experiencing a surge in solar project proposals. Solar is among the fastest-growing form of all new energy projects in the United States and rural counties are on the front lines.

New solar developments prioritize flat land without many trees. This raises understandable land conversion concerns for some counties about the long-term future of farming communities. But some counties, landowners and developers are demonstrating with agrivoltaics that the presence of solar energy generation does not mean agriculture has to disappear.

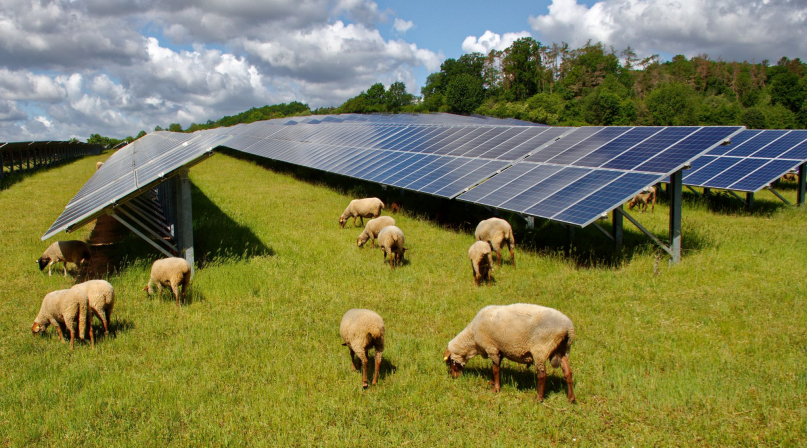

The field of agrivoltaics aims to maximize efficiencies between agriculture and photovoltaic cells otherwise known as solar cells, to use farmland as a multiple-use asset.

For counties, this conversation often surfaces during zoning and siting reviews, where local officials are asked to simultaneously weigh agricultural preservation, private landowner decisions, infrastructure needs and community impact. In some cases, a question remains whether farmland will be permanently lost or if it will simply remain agricultural after the lease. That question has pushed further emphasis on how to keep agriculture on-site during the solar project lifespan.

Solar grazing: Livestock land managers

Solar grazing is one of the more established and quickly expanding forms of agrivoltaics in the United States. Several livestock types are used to varying degrees across the country, but sheep grazing has expanded beyond pilot projects and is increasingly used. When integrating grazing, developers and operators contract with local ranchers to manage vegetation across solar arrays using grazing herds rather than teams of mowers and weed whips.

Gilliam County, Ore. is home to Pachwáywit Fields, a sprawling 1,189-acre solar farm that is now one of Oregon’s largest operating solar facilities. It also incorporates grazing. The project is located on land historically used for winter wheat in a community that is still heavily agricultural. During peak growing months, hundreds of sheep graze the site. This manages vegetation and adds nutrients to the soil while supporting local livestock producers. County review and approval of the weed control plan created a window for the county to weigh in on the use of agrivoltaics, even with a project that was largely under state permitting authority.

Sheep are well suited to solar sites. They are more nimble than cattle, allowing them to move easily among panel rows and reach vegetation under racking systems without damaging equipment. Grazing patterns of sheep target both grasses and broadleaf plants, keeping growth low enough to avoid shading panels while still maintaining ground cover.

For solar operators tasked with maintaining leased land, grazing can reduce vegetation management needs and support community goals on site. In parts of the country with ample rain and fast-growing vegetation, plant matter can obstruct portions of panels if not managed, spurring growth of grazing material.

In drier regions, such as Gilliam County, Ore., well-planned grazing schedules can help reduce fire risk by limiting excess vegetation between rows. For local ranchers, grazing contracts can provide additional pasture access that may have been closed off.

Some counties also directly address grazing in county ordinances. Washington County, Va., for example, includes language in its amended solar ordinance encouraging dual-use utility-scale solar projects, including grazing. This doesn’t require or limit land use, but it can aid in communicating the goals and priorities of the county to applicants regarding vegetation management and expectations during the life of the project.

Pollinator habitat and native vegetation

Pollinator habitats or a focus on native seed mixes is another common agrivoltaics practice that has gained notable traction. Instead of turf grass, noxious weeds or frequently mowing an unplanned mix of vegetation, some sites intentionally focus on native seed mixes or pollinator-friendly vegetation. Attention to these pollinator mixes between panels or buffering the project can attract insects associated with pollination while stabilizing soils and reducing erosion.

A Kenosha County, Wis. ordinance covering solar standards includes detailed ground cover and buffer provisions that call for perennial vegetation for the duration of operation. The ordinance ties expectations to the project plan and ongoing compliance responsibilities but leaves room for different approaches for meeting these standards. This emphasizes vegetation standards that support soil health and habitat while remaining compatible with agricultural land uses.

During operation periods, pollinator plantings can lead to maintenance efficiencies. Once established, deep-rooted native plants are often more resilient to local conditions, contributing to lower maintenance actions than conventional grass. For surrounding agricultural areas, healthy pollinator populations may lead to spillovers in supporting crop productivity beyond the immediate solar site.

Counties have played a role in encouraging these practices through zoning standards, site plan requirements or voluntary developer-driven approaches. Some counties like Stearns County, Minn., which requires solar projects to meet Minnesota’s voluntary beneficial habitat standard, take a prescriptive approach, while others take a more flexible approach working with counties on a case-by-case basis. Regardless of approach, many counties can act as conveners among developers and the community to ensure projects reflect community values.

What counties are sorting through

Some of the biggest questions on solar development in counties lie at the intersection of land use, agriculture and infrastructure development, yet this is also where agrivoltaics practices sit. Grazing, specifically with sheep, and pollinator plantings are among the most common forms of agrivoltaics, but agrivoltaics is not a single model and does not fit every location, so concepts are being applied to pilot cattle grazing, row crops and beekeeping projects across the country. Soil, climate, existing farming practices and community desires are all factors shaping possibilities and where it can be applied.

What is clear is that solar development does not always require that land be treated as permanent loss of agricultural value as counties gain further understanding of agrivoltaic practices.

Related News

NACo launches 2026 Rural Energy Academy Cohort to support county decision-making on new energy projects

NACo announces the launch of the 2026 Rural Energy Academy technical assistance cohort.

U.S. Department of the Interior issues new NEPA regulations recognizing local governments as cooperating agencies

On February 23, the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) announced a final rule updating the Department’s regulations for implementing the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA; P.L. 91-190). In a step forward for counties, the final rule reinstates provisions that name local government agencies as cooperating agencies during the NEPA environmental review process.

House Agriculture Committee advances 2026 Farm Bill

On March 5, the House Agriculture Committee voted to advance its version of the 2026 Farm Bill.