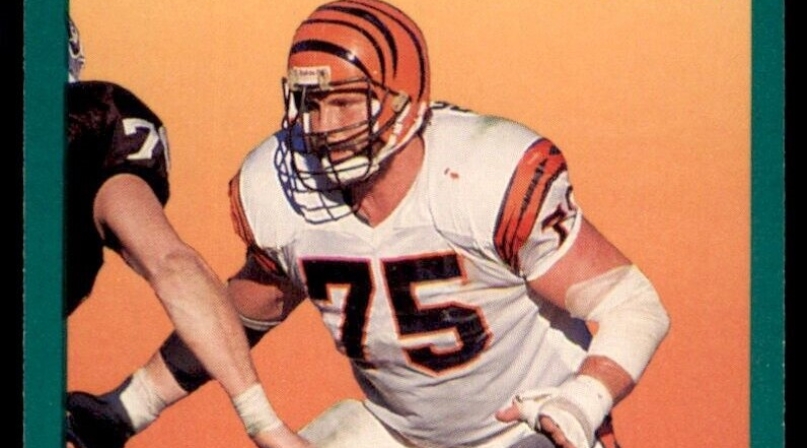

Iowa county supervisor reflects on NFL career, 1989 Super Bowl

Key Takeaways

What does one do after fulfilling a childhood dream of playing in the Super Bowl? For Bruce Reimers, the answer was to become a county supervisor.

Reimers, now serving his third term as a Humboldt County, Iowa supervisor, spent 10 years as an offensive lineman in the NFL, with the Cincinnati Bengals and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. He played on the Bengals team that went to the 1989 Super Bowl playing against the San Francisco 49ers.

“I was so blessed — it’s hard to put into words,” said Reimers, who grew up with six siblings. “That was all I wanted. As a little boy, when we came home from church, we only had one TV, so it was like whoever gets to the TV first. So I watched football all day long — I just loved the sport.”

It’s been more than 30 years since Reimers’ final season. He’s since become a farmer, started a grain trucking business, coached his high school alma mater’s football team to a state championship win and gotten involved in local government. However, if it were up to him, he would be playing football forever, he said.

“When I got cut, I tore all the ligaments in one ankle,” Reimers said. “I was always giving my wife a bad time. ‘When you come home, if the phone is hanging from the cord and it’s on the floor, I will try to call you and let you know where I’m at, because somebody called and they need an offensive lineman, and I’m going.’

“If I could play, even right now, if I could play one more series — a 63-year-old guy with two plastic knees — I mean, that’s my dream.”

‘I’m a small-town person’

After spending a decade traveling around the country playing with and against Hall of Famers, Reimers settled back in his hometown of Humboldt County. One of the smallest in Iowa, the county has a population of under 10,000.

“People laugh at me, ‘Why would you want to go back to a small town?’” Reimers said. “That’s just me, I’m a small-town person.”

It’s the sense of community that makes small Midwestern counties special, he said.

“At one time, I had three or four different neighbors’ keys, because some would go to Florida or Arizona or somewhere warm,” Reimers said. “Each house had their own instructions, ‘If you see Reggie’s light come on in the middle of the wintertime inside the house, that means that the temperature is too low, so call his son because he needs to come out and turn the thermometer up just a little bit.’

“That’s the way I grew up, everybody takes care of everybody.”

Reimers never envisioned himself in government, but it was a gas station stop to refill his morning coffee that planted the seed, he said. He was pouring a fresh cup, chatting to some people he ran into, when he heard that a county supervisor was resigning. Someone suggested that Reimers run for the open spot. Initially brushing it off, he became more convinced after he sat more with the idea of it, he said.

Joining a new team

“The more I thought about it, the more I thought, ‘You know, I’m always one of the people that would be the first to critique, and maybe instead of critiquing, I had the ability to be on the other side and help figure out plans or ways of solving problems.’”

While some days as an elected official can be “frustrating,” he said he enjoys the work and views himself and the county’s four other supervisors as a team.

“We’re not trying to reinvent the wheel here, we’re just trying to make the wheel work better,” Reimers said. “But you feel good when you feel like we’re doing stuff to help the community and the county … I figure if you’re reelected, then people must appreciate you, or at least feel like they have a voice.”

Once he decided to pursue the county supervisor role, Reimers stepped down from helping coach Humboldt High School’s football team, which he had done for 23 years, including the school’s first and only state championship win in 2006. While Reimers isn’t formally involved with the team anymore, he said he still consults with the head coach, who goes to his church and sends him videos of the team.

Coaching helped “heal the part of [his] heart that got ripped out when [he] was released” from the NFL, he said.

“That was one of the neatest things, other than my Super Bowl, that I got to say that I was a part of,” Reimers said. “It was so fun to watch kids develop. Sometimes they’d say, ‘I can't do that,’ and I’d say, ‘I know you can do it.’ Whether they’re young and you’re working in the weight room, or whether they’re a senior and you’re trying to get them to be a better leader, it was one of the ‘funnest’ times that I’ve had.”

Having had many teammates over the years who have suffered from the impact of numerous concussions, Reimers said more needs to be done about protecting players from CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy), particularly young children.

“Little kids should not be playing full contact tackle football, I don’t care,” Reimers said. “Their bodies are not developed enough for them to be taking hits the way some of the kids are taking, and I really believe that the NFL should make a stance to say, ‘There’s gonna be a time when kids are old enough to play, but we sure as hell don’t need those little kids taking a lick and ending up severely hurt.’”

Although Reimers’ Bengals team lost in the final seconds to the San Francisco 49ers in 1989 in one of the closest Super Bowls of all time, he said that doesn’t mean he’s rooting against them this go around with the Kansas City Chiefs. He’s a big fan of 49ers quarterback Brock Purdy, a fellow alum of Iowa State University, where Reimers was inducted into the Letterwinners Club Hall of Fame in 2009.

“I cringe at the thought that I’ve been kind of a closet 49ers fan, but this kid’s a player,” Reimers said. “I’m looking forward to a good game and I wish Brock the best.”

‘Keep reaching for your dream’

Reimers keeps in touch with some of the other offensive linemen from the Bengals and helped surprise Boomer Esiason, his former teammate and the 1988 NFL MVP quarterback, at an Ohio fundraiser he threw for his foundation, which works to raise awareness and funding for people living with cystic fibrosis.

When Reimers’ grandchildren see football cards and photos from his NFL days, he said they don’t recognize him. But for him, it’s something he’ll always feel a part of and hold close, he said.

“The crazy part is if there’s a good game on and I watch it and I go to bed, my brain starts going back to when we played,” Reimers said. “And then the next day I'll tell my wife, ‘God, I couldn't sleep, I couldn't find my shoes.’ ‘What do you mean?’ ‘Well, we were playing, and I couldn't find my shoes.’ She's like, ‘Oh my God, dear.’

“But that’s all I was thinking [about], was football. Even old guys have dreams, so I would tell every kid, that’s the only way that you’re going to keep moving forward is to keep reaching for your dream.”

Related News

Now I know I can adapt my communication style

San Juan County, N.M. Commissioner Terri Fortner spent her career working with people one-on-one, but she overcame hangups about online communication when the pandemic forced her onto video calls when she first took office.

County service meets a veteran’s need for purpose in Spotsylvania County, Virginia

After Drew Mullins transitioned from a high-performance lifestyle in the military, he found the environment and purpose he sought when he took office in his county.

Now I know that solid waste is complicated

Custer County, Idaho Commissioner Will Naillon says solid waste removal is "one of the things that people often take for granted until it’s their job to make sure it happens... that’s the story of being a county commissioner."

County News

NFL star talks trials, triumphs after football