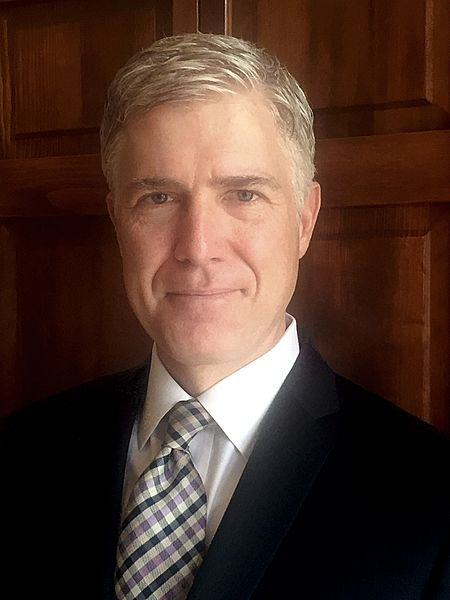

Confirmation by fire: How might the confirmation process affect Justice Gorsuch?

How will one of the most political Supreme Court nominations in recent history, affect Gorsuch?

Justice Neil Gorsuch is certainly aware of the fact that his confirmation was one of the most politically driven in recent memory.

Only time, and perhaps his idiosyncrasies on the bench, will tell us whether, like Chief Justice John Roberts, Gorsuch is concerned about the court’s being perceived as apolitical.

It is difficult for those of us who treasure our democracy and our legal system in particular to accept the notion that Supreme Court justices — and even regular old judges — are chosen for political reasons. We want to believe that our judges dole out the law evenly, intelligently, and objectively and are picked based on their perceived ability to do so — with justice as the end result.

It is difficult for those of us who treasure our democracy and our legal system in particular to accept the notion that Supreme Court justices — and even regular old judges — are chosen for political reasons. We want to believe that our judges dole out the law evenly, intelligently, and objectively and are picked based on their perceived ability to do so — with justice as the end result.

But beyond the thin veneer of choosing someone with stellar academic credentials who has had an impressive legal career, politics always looms large in the selection of Supreme Court justices. This is as much because a president doesn’t want to see measures he worked on overturned and wants his political party to succeed, as it is that Supreme Court justices are a key part of a president’s legacy. A 49-year-old justice like Gorsuch may sit on the court for 30 years.

It is impossible to deny that politics played a significant role in the selection of Justice Gorsuch. President Obama never would have nominated Merrick Garland, a 63-year-old moderate white man, had Republicans not said they would hold no confirmation hearings no matter who Obama nominated. While Republicans claimed they wanted “the people” to pick the next Supreme Court justice, they were very quick to congratulate themselves on the effectiveness rather than the correctness of not holding confirmation hearings for Garland when Donald Trump won the election.

Candidate Trump came up with two lists of 21 people from which he vowed to choose for Supreme Court nominations. To come up with these lists, he let voters know he sought input from two conservative organizations, the Federalist Society and the Heritage Foundation. It was no coincidence that all but one person on the lists were current judges with long track records to avoid “another Justice Souter.” It also may not be a coincidence that the person chosen — Justice Gorsuch — was one of the two judges on the lists the authors of Searching for Scalia considered to be the most Scalia-like.

And of course, Gorsuch was confirmed only after Senate Republicans deployed the “nuclear option,” meaning Supreme Court nominees may advance with the vote of a simple majority. The former 60-vote threshold made it more likely nominees would have to garner wide bipartisan support to be confirmed.

Will the fact that Gorsuch was confirmed in such a politically charged environment affect him and how he votes on the court, particularly in cases affecting states and local governments?

He soon will be tested in big cases. At some point the Supreme Court will rule on the legality of President Obama’s or President Trump’s Clean Power Plan and the “waters of the United States” definitional rule.

No matter how he votes or what he writes it will be impossible to know his true motivations. For example, in these particular cases his votes may have more to do with how he feels about federalism, agency deference and environmental regulation or protection than whether he is a liberal or a conservative, or whether he feels any loyalty to the president who nominated him.

Court observers have speculated Roberts voted to uphold the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate to protect the institutional integrity of the court. Roberts may have feared the court would have looked like a political body if the five conservative-leaning justices, all appointed by Republican presidents, struck down the Democratic president’s signature piece of legislation.

If one looks closer at Roberts’ record, they will find other more subtle idiosyncrasies, which possibly indicate that he is generally concerned about the court’s institutional integrity as a non-political branch of government.

Specifically, Roberts rarely joins the concurring and dissenting opinions of his more conservative colleagues, Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, perhaps simply because he is less conservative than they are. But more subtlety, I can’t help believe that when he assigns himself opinions in small cases involving racial bias, where the court rules in favor of the person who experienced that bias, as he has done this term, Buck v. Davis, and last term, Foster v. Chatman, that he isn’t saying something — conservatives care deeply about irradiating racial bias too.

I expect Justice Gorsuch, like Roberts, in general to be a reliable conservative. But as Justice Gorsuch’s idiosyncrasies become clearer over the years, they may reflect his concern for the court as an institution, just as the Chief Justice’s idiosyncrasies may reflect the same.

NACo is a founder, a funder and a board member of the State and Local Legal Center, headquartered in Washington, D.C. The center extends NACo’s advocacy on behalf of counties to the highest court in the land.

Attachments

Related News

U.S. House reintroduces legislation to address the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy with NACo support

Two bipartisan bills aimed at addressing the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy (MIEP) were recently reintroduced in the U.S. House of Representatives.

U.S. House of Representatives re-establishes Bipartisan Mental Health Caucus with NACo support

On May 7, members of the U.S. House of Representatives appointed new leadership to the Bipartisan Mental Health Caucus, reaffirming their commitment to addressing the nation’s mental health crisis through cross-party collaboration.

New disaster recovery grants now open to support county economic development

The U.S. Economic Development Administration has launched the Fiscal Year 2025 Disaster Supplemental Grant Program, making $1.45 billion available to help communities recover from natural disasters and build long-term economic resilience. Counties affected by major disaster declarations in 2023 or 2024 are eligible to apply for funding to rebuild infrastructure, strengthen local economies and prepare for future disruptions. This program goes beyond immediate recovery, aiming to transform local economies and foster sustainable, long-term economic growth.