Promoting Health and Safety Through a Behavioral Health Continuum of Care

Upcoming Events

Related News

Key Takeaways

By forming strategic partnerships throughout health and justice systems, county leaders are better serving residents with behavioral health conditions such as mental illness and/or substance use disorders. Central to a behavioral health continuum of care, counties are creating practices and programs that help people:

- Before an emergency, by connecting them to treatment and services in the community that target unmet behavioral and physical health needs before they escalate to a crisis

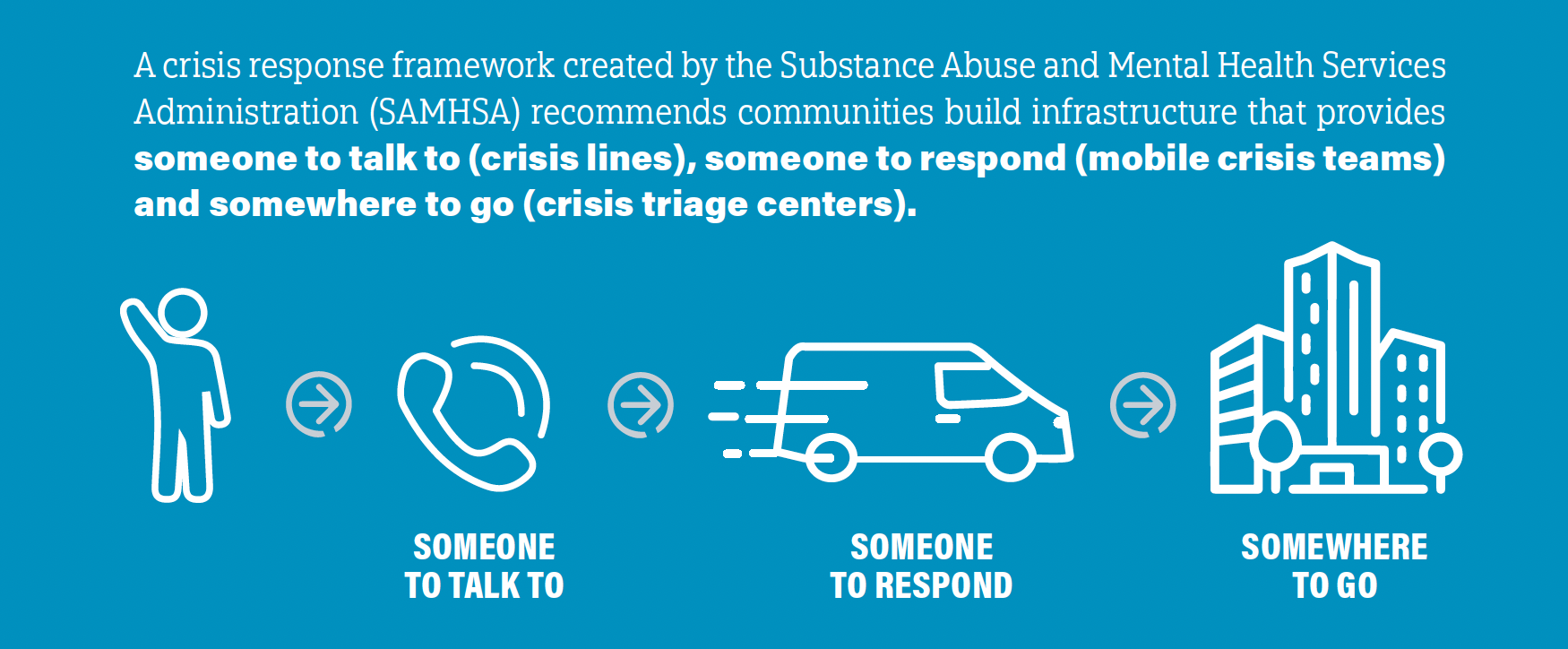

- During an emergency, through a coordinated crisis response system that provides community members with someone to call, someone to respond and somewhere to go, and

- After an emergency, via continuing system collaboration and linkages to social services, peer support and recovery care.

Introduction

Counties play an important role in providing services and support to the approximately 1 in 5 adults in the U.S. who have a behavioral health condition such as mental illness and/or substance use disorder. Annually, counties allocate $100 billion to community health systems – including behavioral health support – and provide services through 750 behavioral health authorities and community providers.1 Despite this investment, more than half of people with behavioral health conditions report not receiving treatment in the past 12 months.2

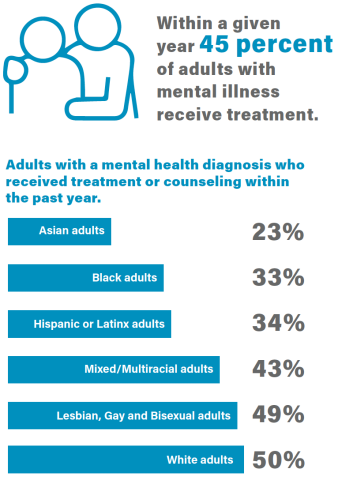

Communities of color have disproportionately low levels of access to behavioral health care; Asian, Black and Hispanic or Latinx adults with a mental health diagnosis are less likely to receive treatment or counseling than white, multiracial or LGBTQ+ adults.3 In addition, 134 million people live in a designated mental health professional shortage area and many community members, especially those living in rural or underserved areas, lack access to high-quality treatment.4

Counties are using a public health approach to support community members with behavioral health conditions. By directing resources to community-based treatment and services, counties can better serve residents with behavioral health conditions, reduce reliance on the criminal legal system and direct valuable resources towards improving stability and health. Establishing a robust continuum of care for people with behavioral health conditions will ensure local residents have equal opportunity to thrive. This brief outlines the elements of a behavioral health care continuum and strategies counties can implement to assist community members with a behavioral health condition.

Elements of the Behavioral Health Continuum of Care

People with behavioral health conditions often have needs across government systems and are better served when those systems work together. Essential to full continuums of care is organized integration to offer seamless transitions that connect community members to appropriate care 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. A recovery-oriented continuum can proactively address potential signs of an emergency, stabilize a person in distress and equip them with tools to mitigate future emergencies. Counties can effectively help residents by supporting them throughout the lifecycle of their behavioral health condition, offering services and support based on community need, while ensuring an expanded approach beyond emergency response to comprehensive care.

Continuums of care help people before, during and after a behavioral health emergency. This interconnected system deflects and diverts people away from justice-system involvement and emergency room visits through an array of services that assist community members, regardless of their condition’s severity level or their gender, age or cultural background.

Before a Behavioral Health Emergency

Counties play an important role in providing prevention and early intervention services that focus on the environmental and social conditions impacting community members’ health and wellness. Community members with unmet behavioral health treatment needs may face challenges such as housing and employment instability, untreated medical concerns, prior interpersonal trauma, unsafe living conditions and lack of access to basic necessities. By moving services “upstream,” counties can address the social determinants of health, which consist of core drivers of health and behavioral health.

To improve the environmental conditions where residents live, learn, work and play, counties can offer housing solutions such as crisis, transitional or long-term housing; deploy trauma-informed services like Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams; support students with school-based mental health programs; and increase access to care through the expansion of telepsychiatry, among other approaches.

*Stanislaus County, Calif. developed a mental health prevention and well-being program targeting the Latinx/Spanish-speaking community, Realizando Alianza & Inspirando Sabiduría (RAIZ) Promotores. The program deploys community health workers (promotores) from local neighborhoods to inform residents of the early signs of mental health conditions and strategies to proactively correct risk factors. Promotores advance prevention-focused and community-based education and activities by serving as a bridge between community members, health care institutions and social service providers. In 2020, more than 1,600 residents participated in the program.5

* The Department of Mental Health in Niagara County, N.Y. offers a Crisis Services Call Center for county residents to call for social and human service inquiries and referrals. Operating 24 hours a day, 365 days per year, the Call Center Phone Aides provide callers with information on housing, counseling, substance use treatment, food pantries and other community resources. They also provide immediate assistance and connection to care for individuals experiencing mental health emergencies. The service is confidential and free, offering a safe space to ask questions, share concerns and request assistance for themselves or others.

* Building on existing work and in partnership with the city of Houston and a local nonprofit, Harris County, Texas launched a $65 million initiative to support people experiencing housing instability during the COVID-19 pandemic by providing permanent supportive housing (PSH) and other housing options. The initiative uses federal funds such as resources from the CARES Act. This Housing First program provides people experiencing persistent homelessness and behavioral health conditions with permanent, affordable housing as well as a navigator and case manager. The case manager provides supportive services and connects participants to mental health support, income sources and more. Between October 2020 and January 2022, more than 1,000 people were permanently housed through PSH, and the time between intake and move-in decreased from 70 to 30 days because of the enhanced resources.6

“Everyone deserves access to a safe, stable and affordable place to call home. Access to housing and shelter is a fundamental human right, yet we often treat housing as a commodity. We have an opportunity to end chronic homelessness in our community.”

– Rodney Ellis, Precinct 1 Commissioner, Harris County, Texas7

By dedicating resources to help community members tackle the socioeconomic, physical and emotional drivers of a behavioral health condition, county programs and services can reduce the likelihood of an emergency. Despite counties’ best efforts, individuals do still experience behavioral health emergencies, and county leaders are finding innovative ways to address these incidents through a public health approach.

During a Behavioral Health Emergency

To support community members during a behavioral health emergency, counties play an important role in providing alternatives to emergency room visits or legal system involvement. National initiatives such as the Safety and Justice Challenge, Stepping Up and Familiar Faces Initiative work to reduce the disproportionately high rate of people with behavioral health conditions involved in the criminal legal system. To address this challenge, county leaders are partnering with state, regional and county behavioral health authorities and providers to create a crisis response system that prioritizes health-focused approaches to serve people during an emergency.

A critical component of any crisis response system is hiring and training clinicians and health professionals with the experience to de-escalate a situation without relying on law enforcement intervention. Leveraging clinicians, rather than first responders in appropriate situations, can allow law enforcement and EMS to focus on other public safety or medical priorities.

Someone to Talk to: Crisis Lines

Crisis lines are critical in providing immediate care and resources for individuals experiencing a behavioral health emergency. Innovative county crisis lines divert calls to health care clinicians who can triage the emergency, de-escalate situations, dispatch mobile crisis teams and/or connect individuals to community-based providers through a “warm handoff.”

* In Baltimore County, Md., the Department of Health and Human Services and 911 Communications Center launched a Call Center Clinician program. Mental health clinicians screen calls and divert those that meet specific criteria to behavioral health support, rather than law enforcement or emergency response. The county is dedicating $1.6 million in federal funding to the call center and expansion of its mobile crisis team.

“This expansion is an important step forward that will help Baltimore County better provide those in crisis with the help they need while continuing to help our first responders to strengthen communities and save lives.”

– Johnny Olszewski, County Executive, Baltimore County, Md.9

* The Taylor County (Texas) Sheriff’s Office partnered with the Abilene police and fire departments, Betty Hardwick Center and Avail Solutions to include a remote crisis line behavioral health clinician.10 The clinician is included on three-way 911 calls from community members experiencing a behavioral health emergency to triage the call and determine next steps.

* Trained clinicians staff a 24-hour, non-911 crisis line seven days a week in Multnomah County, Ore. Staff provide free behavioral health support, referrals to treatment and service providers and information on non-crisis community resources in any language. Staff can also dispatch mobile crisis response 24 hours a day, seven days a week as requested.

When crisis lines are staffed with trained clinicians, many emergencies can be resolved over the phone without the need for further engagement. However, some individuals need a different level of care. In these cases, the crisis line clinicians can also dispatch mobile crisis teams, where available.

Launching the 988 Crisis Line

The nationwide transition to 988 in July 2022 provides an easier way for people experiencing mental distress to access the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. With this shift, counties will have an opportunity to expand local mental health safety net and help community members access treatment. People experiencing a behavioral health or suicidal emergency can chat, call or text this number to speak to a trained counselor who can offer emotional support. Counties play an important role in providing a robust behavioral health care continuum so counselors can provide referrals and people have access to the critical support necessary for recovery and prevention. With nearly 2.4 million calls to the Lifeline in 2020, jurisdictions expect a demand increase with the 988 transition.11

Someone to Respond: Mobile Crisis Teams

Many counties have worked with local behavioral health providers or departments to create mobile crisis teams (MCTs). Sometimes called crisis response teams or units, MCTs are community-based, face-to-face interventions that provide the least restrictive services to a resident wherever they are physically located. MCTs provide stabilization and treatment as well as deflect individuals away from the criminal legal system. After on-site evaluation and intervention, MCTs can refer people to treatment and/or services as needed. MCTs are effective at diverting people from psychiatric hospitalization, connecting individuals to outpatient care and efficiently utilizing public dollars.12

Counties have launched civilian-only MCTs to reduce law enforcement interaction and offer access to trained health professionals. The civilian-only MCT teams often include only licensed health care clinicians, peer support workers and/or social workers. Many of the MCTs replicate the Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS) model, which originated in Oregon. This long-standing national model for civilian-only response provides an alternative to law enforcement dispatch for social service-related calls.

*Nassau County, N.Y. deploys an MCT of licensed social workers and specially trained nurses to intervene when people are in distress. The team travels to the resident’s location to assess the environment, evaluate their mental health condition and refer them to appropriate services.

* In Missoula County, Mont., an MCT, pairing a medic and mental health therapist, can respond to emergency mental health calls. Originally funded by the county, city of Missoula and Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, the county is using almost $370,000 in ARPA funding to increase the number of hours and teams available.13 During the pilot phase of November 2020 to June 2021, the team responded to 537 calls, leading to 169 emergency room and 13 jail diversions and saving about $250,000.14

Recognizing the importance of responding to emergency calls through a health perspective, many counties have developed multi-disciplinary MCTs. These units pair crisis intervention team (CIT) trained law enforcement officers with health professionals to respond to certain calls for service. Often, these MCTs are dispatched to calls that include a safety concern or active threats of violence.

* The System-wide Mental Assessment Response Team (SMART) in Summit County, Colo. pairs a law enforcement officer with a behavioral health specialist. This team works together to de-escalate the situation and stabilize an individual. A third team member, the case manager, provides follow-up support and connects the community member to resources that address mental health conditions, housing instability and food assistance. Since the program’s inception in January 2020, SMART has had no uses of force or made any arrests.15

*Fairfax County, Va. is dedicating $2.3 million of its ARPA funds to a co-responder model. The program pairs a CIT police officer and licensed clinician to respond to behavioral health-related 911 calls. Between March 2021 and January 2022, over 70 percent of the calls received were de-escalated and diverted into other services without resorting to a Temporary Detention or Emergency Custody Order.16 The co-responder program ensures agencies are using the least restrictive means possible and providing the right intervention, at the right time and by the right person.

Innovations During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Counties continue to play an important role in supporting community members’ behavioral health needs during the COVID-19 pandemic by deploying innovative programs and practices to increase access.

* The Linn County, Ore. Department of Health and Human Services received funding from the Federal Communications Commission to implement telehealth services for community members experiencing a behavioral health emergency. Expanding services through telehealth allowed more residents to access care, a third of whom live in remote or rural areas.

* Recognizing the Latinx community would be hit hard during the pandemic, the Crisis Hotline in Blaine County, Idaho supported a bilingual support line to answer pandemic-related questions and connect residents to behavioral health and social services.17 The organization also provided care packages to children and their families to keep them socially and emotionally active. The county dedicated $18,000 in ARPA funds to support the Neighbors Helping Neighbors program and add 20 bilingual team members to assist the hotline.

*Clackamas County, Ore. formed mobile “Go Teams” at the start of the pandemic to provide psychological first aid. The teams met residents in the community to help people with early signs of emotional and social problems and minimize potential long-term impacts. The county also launched Clackamas Safe+Strong, with funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), to provide ongoing behavioral health services during the pandemic. Acknowledging its success, the board of county commissioners approved the use of ARPA dollars to continue the Clackamas Safe+Strong program.

“With these programs, what we have really done during COVID is say ‘this is hard and we are here to meet you right where you are with whatever the challenge is and we are going to support you through it.’”

– Sonya Fischer, Commissioner, Clackamas County, Ore.18

Somewhere to Go: Stabilization and Triage Centers

Some community members may need a different level of treatment than the options available over the phone or through an MCT when experiencing a behavioral health emergency. Counties are increasingly building or partnering with crisis triage or stabilization centers to meet this need. While the design and details vary, these centers often provide community members with access to out- and in-patient services, peer support networks, withdrawal management, medication adjustment, counseling, therapy and/or longer-term residential care. Many centers offer a dedicated first responder drop-off area and accept referrals and walk-ins. Health Management Associates’ model facilities framework integrates health care, law enforcement, criminal justice and emergency agencies through coordinated, community approaches aligned with best practices. One such example is federally-funded Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs). These clinics are community-based care providers offering comprehensive, 24 hour behavioral health treatment through evidence-based approaches and care coordination with hospitals.19

“We are so proud of the collaborative effort of Justice Stakeholders and the Community in opening the Living Room Wellness Center. This center employs a “no wrong door” nationally recognized model of support for people with mental illness and provides its guests with a warm hand-off to resources. It aims to decrease repeat police service calls, unnecessary hospitalizations, reduce overuse of our jail and provide certified Peer Support Specialists to assist navigation, utilization and retention of services.”

– Sandy Hart, Board Chair, Lake County, Ill.

* The Deschutes County (Ore.) Stabilization Center, a CCBHC, provides short-term mental health treatment, assessment and stabilization. Community members can walk in or law enforcement and community providers can refer them to services 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The Center provides crisis intervention, peer support, case management, medication support and a respite unit with recliners as a space to decompress and reengage in their recovery. Between June 2020 and January 2022, the Center conducted over 5,000 visits, served more than 1,600 individuals and diverted approximately 30 percent of residents from the emergency room.20

* Through the federally funded Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program, Lake County, Ill. received $750,000 to staff and supply a 23-hour Crisis Triage Stabilization Center. The county also expanded its Living Room Wellness Center to include a police drop-off option. The Living Room pairs guests with a peer counselor and offers crisis intervention in addition to basic needs such as food, clothes, showers and transportation. The service provider, sheriff’s office and state’s attorney’s office provided funding for the expanded services. Between August 2020 and August 2021, the Living Room served over 300 people.21

County service provision plays an integral role in helping community members during a behavioral health emergency by providing them with someone to talk to, someone to respond and somewhere to go. As an individual’s immediate needs are met, providers and counties are continuing to support residents after an emergency.

After a Behavioral Health Emergency

Community members are more likely to succeed in recovery when they have support and connections to services that target their social determinants of health after an emergency. A behavioral health continuum that connects individuals to ongoing treatment can more effectively respond to their underlying needs and reduce recurrent crises by building their ability to navigate future challenges. To achieve this goal, counties can assist community members after an emergency by connecting residents to community-based services, following-up on progress, supporting peer engagement and providing case management.

* In Erie County, N.Y., a set of programs support community members with an opioid use disorder or after an overdose. Individuals with an opioid use disorder who visit an emergency room have access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) providers in the community. After an overdose, police officers submit a report of the incident, which triggers a peer navigator referral. The peer navigator visits the person at home and schedules appointments with treatment providers. A suburb in the county saw a 61 percent decrease in overdoses and 69 percent decrease in overdose deaths after implementing the referral program between 2016 and 2018.22

*Waukesha County, Wis. offers a Community Support Program (CSP) that provides treatment, rehabilitation and outreach services to adult residents with a long-term mental health condition. A case manager develops individualized treatment plans and coordinates all services. Additionally, the county’s Comprehensive Community Services (CCS) program is a community-based program for adults and youth offering psychosocial rehabilitation services. Both programs are funded by Medicaid. As of February 2022, 121 residents participate in CSP, and 148 community members are enrolled in CCS.23

* The C3356 Comprehensive Care Center in Buncombe County, N.C. offers outpatient services for community members to promote their recovery journey. In addition to therapy and counseling, the Center offers a Peer Living Room. In this program, peer specialists with lived experience can offer guidance to individuals in recovery and a connection to community resources. In 2020, between 300 and 1,250 individuals signed into the Peer Living Room monthly.24

“The C3356 offers services in a kind and compassionate environment, often times led by peers with lived experience, to meet people wherever they are on their recovery and wellness journey. Importantly, the center offers crisis and substance use detox services as well as mental health/substance, outpatient services, peer and family support and a pharmacy, all in one convenient location.”

– Jasmine Beach-Ferrara, Commissioner, Buncombe County, N.C.

Key Considerations for Implementation

Counties can save lives and conserve resources while improving community well-being by building an accessible, just, effective and interlinked behavioral health continuum. To accomplish this goal and go beyond the integral coordination required, counties can consider:

- Developing a working group or task force that involves key stakeholders and centers the voices of people with lived experience

- Finding opportunities to deflect and divert community members from the criminal legal system and emergency department to appropriate treatment

- Scaling up opportunities through pilot initiatives

- Leveraging data and technology to track outcomes and inform case management

- Directing resources to underserved communities and people with the highest need, and

- Adopting “no wrong door” policies and a whole person approach.

Conclusion

Counties are well-positioned to develop and build collaborative behavioral health continuums of care that increase access to effective, high-quality treatment and services for community members living with behavioral health conditions. Through complementary and strategic coordination throughout systems and agencies, counties can deploy resources to support residents with diverse needs. Addressing needs before, during and after an emergency leads to better health, safety and well-being for community members and the community alike.

Acknowledgements

Support for this report was provided by the MacArthur Foundation. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.

This report was researched and written by Chelsea Thomson, Justice Program Manager, with support and guidance from Blaire Bryant, Legislative Director, Health, and Nastassia Walsh, Director, Programs and Operations.

References

1. National Association of Counties, “Behavioral Health Matters to Counties,” (March 4, 2021) available at https://www.naco.org/sites/default/files/documents/Behavioral%20Health%20Matters_1.pdf (January 31, 2022)

2. National Alliance on Mental Illness, “Mental Health Care Matters,” (2020) available at https://nami.org/NAMI/media/NAMI-Media/Infographics/NAMI_MentalHealthCareMatters_2020_FINAL.pdf (February 1, 2022)

3. Latoya Hill, Samantha Artiga and Sweta Halder, “Key Facts on Health and Health Care by Race and Ethnicity,” (January 26, 2022) available at https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-facts-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ (February 1, 2022)

4. National Alliance on Mental Illness, “Mental Health By The Numbers,” (n.d.) available at https://nami.org/mhstats (February 1, 2022)

5. Ruben Imperial, “MHSA Three Year Program and Expenditure Plan for Fiscal Years 2020-2023 Annual Updates for Fiscal Years 2019-2020 and 2020-2021,” (June 24, 2021) available at http://www.stanislausmhsa.com/pdf/public/FINAL_AU_PEP.pdf (February 1, 2022)

6. Coalition for the Homeless, “Community COVID Housing Program,” (n.d.) available at https://www.homelesshouston.org/cchp (February 8, 2022); Aubry Vonck, “CCHP Explained: Bridge to Permanent Supportive Housing,” (April 28, 2021) available at https://www.homelesshouston.org/cchp-explained-bridge-to-permanent-supportive-housing (February 8, 2022)

7. Catherine Villarreal, “Press release: City of Houston and Harris County Announce Unprecedented Investment to House the Homeless.” (January 26, 2022) available at https://www.homelesshouston.org/press-release-city-of-houston-and-harris-county-announce-unprecedented-investment-to-house-the-homeless (February 2, 2022)

8. Pamela Owens, Ryan Mutter and Carol Stocks, “Mental Health and Substance Abuse-Related Emergency Department Visits among Adults, 2007,” (July 2010) available at https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb92.pdf (February 2, 2022); Treatment Advocacy Center, “Road Runners: The Role and Impact of Law Enforcement in Transporting Individuals with Severe Mental Illness,” (May 2019) available at https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/road-runners (February 2, 2022)

9. Baltimore County, “Olszewski Announces Expansion of County’s Behavioral Health Crisis Emergency Services,” (April 6, 2021) available at https://www.baltimorecountymd.gov/county-news/2021/04/06/olszewski-announces-expansion-of-countys-behavioral-health-crisis-emergency-services (February 8, 2022)

10. Laura Gutschke, “New Abilene 911 program helps callers in mental health crisis,” (February 1, 2019) available at https://www.reporternews.com/story/news/2019/02/01/new-abilene-program-addresses-911-mental-health-call/2747350002/ (February 9, 2022)

11. Vibrant Emotional Health, “988 and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline,” (2021) available at https://www.vibrant.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/988_two_pager_2021-2.pdf (January 31, 2022)

12. SAMHSA, “National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care Best Practice Toolkit,” (2020) available at https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/national-guidelines-for-behavioral-health-crisis-care-02242020.pdf (January 31, 2022)

13. Megan Mannering, “Missoula's mobile crisis unit coming together as more funding is secured,” (September 2, 2020) available at https://www.kpax.com/news/missoulas-mobile-crisis-unit-coming-together-as-more-funding-is-secured (February 10, 2022); Missoula County, “ARPA 2021 Funded Projects,” (n.d.) available at https://www.missoulacounty.us/home/showpublisheddocument/75507/637686052510000000 (February 2, 2022)

14. Gretchen Neal, “Missoula Mobile Support Team: Pilot Evaluation,” (2021) available at https://missoulacurrent.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/support-team.pdf (February 2, 2022)

15. Email correspondence with Jaime FitzSimons, Sheriff, Summit County, Colo. on February 5, 2022.

16. Email correspondence with Eric Ivancic, Lieutenant, Fairfax County, Va. on February 8, 2022.

17. Karen Bossick, “Neighbors Helping Neighbors Helps Community Get Through the Pandemic,” (June 6, 2020) available at http://www.eyeonsunvalley.com/story_reader/7302/Neighbors-Helping-Neighbors-Helps-Community-Get-Through-the-Pandemic/ (February 3, 2022)

18. “Commissioner Sonya Fischer talks mental health resources,” (August 21, 2021) available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ilmEHECRCWs (February 9, 2022)

19. National Council for Mental Wellbeing, “What is a CCBHC?,”(2020) available at https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/What_is_a_CCBHC_UPDATED_8-5-20.pdf (February 2, 2022)

20. Email correspondence with Holly McCown Harris, Crisis Services Program Manager, Deschutes County, Ore. on February 4, 2022.

21. Jami Kunzer, “Living Room Wellness Center provides jail alternative for those in mental health crisis,” (August 26, 2021) available at https://www.shawlocal.com/lake-county-journal/news/local/2021/08/26/living-room-wellness-center-provides-jail-alternative-for-those-in-mental-health-crisis/ (February 10, 2022)

22. National Association of Counties, “Erie County, N.Y. Law Enforcement and Public Health Collaboration,” available at https://www.naco.org/sites/default/files/documents/ErieCounty_LawEnforce_PubHealth_8.18_LL3.pdf (February 11, 2022)

23. Email correspondence with Bradley Haas, Health and Human Services Supervisor, Community Support Program, Waukesha County, Wis. on February 9, 2022.

24. Buncombe County, “Crisis Response and Behavioral Health Update,” (February 5, 2021) available at https://www.buncombecounty.org/common/jrac/committee/2021-02-05/presentation.pdf (February 3, 2022)