Legislative Analysis for Counties: Federal Permitting Provisions in the Fiscal Responsibility Act

Upcoming Events

Related News

Introduction

On June 3, President Biden signed the Fiscal Responsibility Act (P.L. 118-5/FRA), enacting into law a bipartisan agreement to raise the debt ceiling through 2025 and, with it, longstanding county priorities for streamlining the onerous federal permitting process. Specifically, the FRA amends the review process required under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA/P.L. 91-190) for federally supported infrastructure projects for the first time in over four decades.

As major owners, operators and users of the nation’s transportation and infrastructure assets, counties are pleased to see the inclusion of commonsense permitting reforms. Locally, these changes will mitigate the burden over overly confusing NEPA requirements and instead support project delivery, all the while providing excellent environmental protections for our local communities.

County Role in the Federal Permitting Process

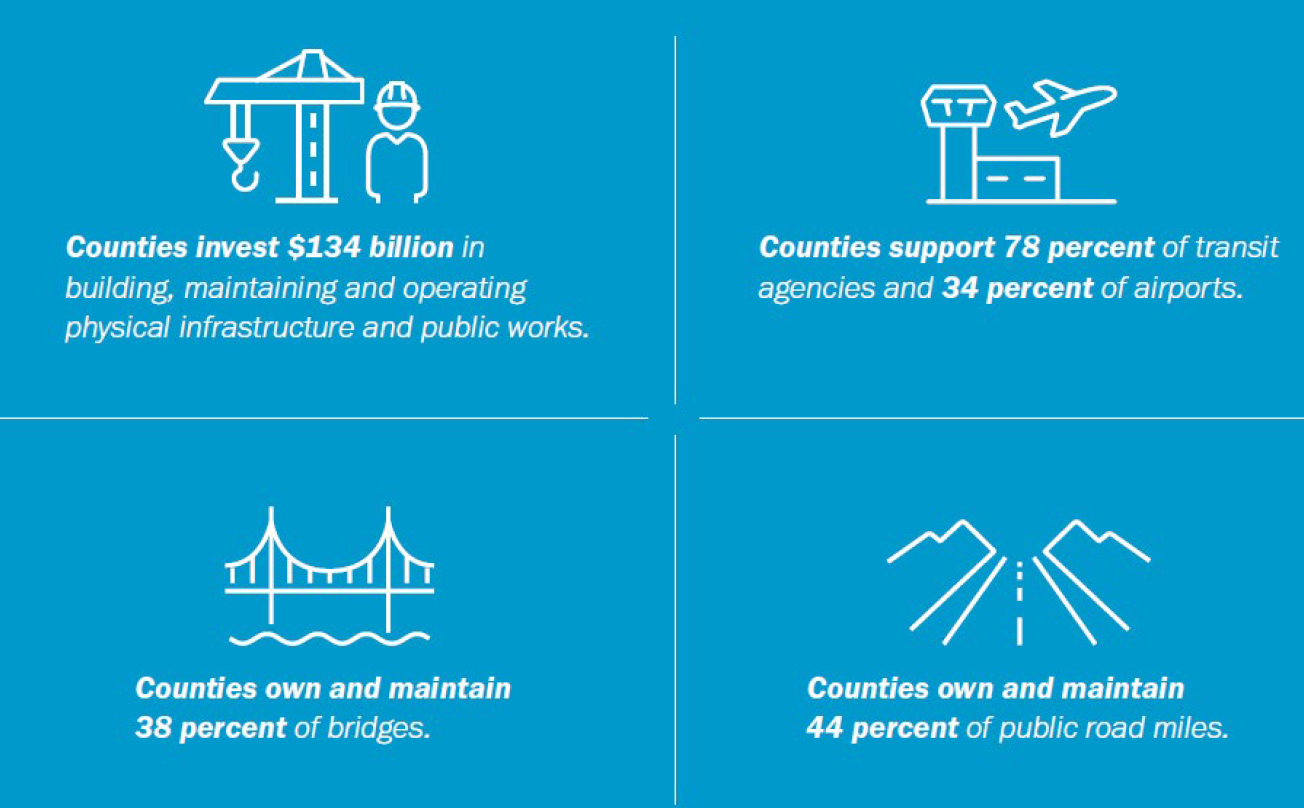

Annually, counties invest over $130 billion in the construction, operation and maintenance of public works, including nearly half (45 percent) of all public road miles and four out of every ten bridges (3 percent) in America owned, operated and maintained by county governments. Concurrently, we directly support over one-third of public airports and transit systems. As a result of our vast public infrastructure responsibilities, we are directly impacted by the environmental review process required under NEPA.

From 2000 to 2020, the National Association of County Engineers (NACE) estimated that the purchasing power for infrastructure by counties has been cut in half. This is largely due to environmental review delays for small projects, resulting in local leaders oftentimes forgoing important projects altogether due to costly NEPA delays exacerbated by the current inflationary environment. This includes requiring reviews for even the simplest of projects, like repairing an existing sidewalk.

Unfortunately, burdensome and duplicative NEPA reviews have unnecessarily delayed and disrupted county infrastructure projects for decades. This is especially true in rural and western jurisdictions where officials must prudently expend public funds limited due to low tax bases and state limits on raising local revenue, and where counties may be subject to complex environmental regulations triggered by federal lands.

NEPA Background

Enacted on January 1, 1970, by President Nixon, NEPA is intended to review the environmental impacts of federally aided infrastructure projects and requires agencies to issue one of three findings where applicable:

- Environmental Impact Statement (EIS): the most in-depth review of a project’s environmental impacts and required where a proposed project has a significant foreseeable impact on the environment

- Environmental Assessment (EA): when a project’s impacts are unclear, an EA takes a higher look at a project and can result in an EIS where impacts or present or a Finding of No Significant Impact where they are not

- Categorical Exclusion (CATEX): applied to projects when the action does not have a significant environmental effect

Since 1982, NEPA has gone untouched by federal legislators. Still, the law continues to be a subject of ongoing partisan battles that often play out in the Executive Branch, where changes to NEPA can be carried out in the form of executive action. This includes Executive Orders (EO) with directives that may vary dramatically between presidential administrations and are easily repealed by a successor.

This was true for the 2017 President Trump EO on “Establishing Discipline and Accountability in the Environmental Review and Permitting Process for Infrastructure” – better known as One Federal Decision (OFD). Among other directives, OFD established two-year time limits, page limits and required a single federal agency to issue a record of decision for covered projects. In 2021, President Biden repealed the OFD EO, reinstating previous policies requiring a broader application of NEPA.

Later in 2021, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL/P.L. 117-58) successfully codified OFD, though not by amending NEPA. Instead, it amended Title 23 of U.S. Code Section 139 by inserting OFD provisions in an existing section that applies only to federally supported transportation projects. The BIL language also fell short by providing agencies with unilateral pathways to extending review deadlines.

Ultimately, OFD and other streamlining provisions directly amending NEPA were enacted into law by the FRA.

NACo has strongly endorsed OFD and other commonsense measures to broadly improve the federal permitting process for infrastructure projects.

Legislative Analysis: Title III – Permitting Reform

The below table outlines key changes the FRA makes to NEPA.

| New Provision | Impact on Existing NEPA Statute |

|---|---|

Limits the scope of NEPA to considering only “reasonably foreseeable” impacts of an infrastructure project |

Adds "reasonably foreseeable" before impacts; Nullifies 2021 federal guidance from CEQ requiring agencies to study the “cumulative impacts” of a project – a practice that results in a broader application of NEPA |

Requires the analysis of negative impacts of taking no action should an agency determine that no action is more appropriate than the proposed project |

Prior language only explicitly required the formulation of reasonable alternatives to a project |

Ensure scientific integrity and the use of data in formulating agency decisions |

Adds explicit language where there was none |

Requires the head of the lead federal agency to consult with other agencies that also have jurisdiction over a project and make any related comments available to relevant federal officials |

Prior language required a “responsible federal official” to carry out this responsibility |

In addition to amending the existing NEPA statute, the FRA also added sections 106 – 111 to the end of NEPA Title I:

- Sec. 106: Procedure for determining the level of review

- Establishes criteria for when an agency does NOT need to review a project, including when a proposed agency action:

- Is excluded by another agency’s categorical exclusion

- Would clearly conflict with the requirements of another law

- Is “nondiscretionary,” meaning it is required by law to be taken immediately to prevent an emergency, where the agency does not have authority to consider environmental factors in making a determination

- Is a rulemaking

- Sets levels of review where environmental impact statements (EISs) are appropriate if an agency is evaluating a project with reasonably foreseeable impacts on the environment and where environmental assessments (EAs) are appropriate should an agency issue a finding of no significant impact or determine an EIS is needed

- Establishes criteria for when an agency does NOT need to review a project, including when a proposed agency action:

- Sec. 107: Timely and unified federal reviews

- Requires multiple federal agencies involved NEPA to designate a lead agency based on factors, including agency level and length of involvement in the project, authority to approve or disapprove, specific expertise on the action’s environmental effects Magnitude of agency’s involvement.

- Establishes that a participating federal agency may appoint state, tribal or local agencies as joint lead agencies

- Designates role of joint lead agencies to fulfill certain responsibilities, including:

- Supervising the preparation of environmental documents

- Requesting participation of each cooperating agency at the earliest opportunity

- Developing schedules, including review timelines and completion deadlines

- Meeting with cooperating agencies

- Empowers a lead agency to designate any federal, state, tribal or local agency involved in proposal to serve as a cooperating agency that may submit comments to the lead agency

- Creates a pathway for local agencies and others substantially affected by the lack of designation by a lead agency to elevate the request to a council

- Requires, to the extent practicable, a lead agency to issue a single record of decision

- Limits page numbers for EISs to 300 pages and EAs to 75 pages

- Requires lead agencies to develop procedures allowing a project sponsors to prepare an EIS or EA under the supervision the agency

- Sets two-year timeline for reviews requiring EISs

- Allows lead agency to work with project sponsor to establish new deadline should the agency be unable to meet the two-year review deadline

- Allows project sponsor to petition the court after a missed deadline and sets guidelines for judicial actions to get the project back on schedule

- Sec. 108: Programmatic environmental document

- Sets five-year “age limit” for environmental documents when new circumstances are not present

- Ex. Since a review was completed, a county has been designated as a nonattainment area by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency due to undesirable air quality where a new review would be in order because the impacts of the project could impact or worsen air quality

- Permits use of environmental documents over five years as long as an agency reevaluates the analysis

- Sets five-year “age limit” for environmental documents when new circumstances are not present

- Sec. 109: Adoption of categorical exclusions

- Allows agencies to adopt the categorical exclusions of other agencies

- Sec. 110: E-NEPA

- Authorizes $500,000 for the Council on Environmental Quality to study the use of digital technologies in addressing the NEPA backlog, including through a portal that would allow project sponsors to track application progress

- Sec. 111: Definitions

- Adds additional exemptions for when projects should NOT be considered a major federal action, which are subject to EISs under NEPA, including:

- Non-federal actions with no or minimal federal funding

- U.S. Small Business Administration business loan guarantees

- Adds additional exemptions for when projects should NOT be considered a major federal action, which are subject to EISs under NEPA, including:

Other permitting reforms in the title would add energy storage to the list of projects eligible for streamlining under a Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST Act/P.L. 114-94) program known as FAST-41 and expedite the completion of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, an under-construction natural gas pipeline running from West Virginia to Virginia.

Conclusion

Counties have long endorsed commonsense changes to the NEPA process that expedite project delivery while upholding excellent environmental stewardship. Still, further work remains, including around reforming the judicial review process, which is often misused by bad actors to delay or prevent important projects – especially in the western United States. As intergovernmental partners and major stewards of public infrastructure, counties will continue to work with our federal partners to streamline the federal permitting process.