The Big Shift: An Analysis of the Local Cost of Federal Cuts

Author

Teryn Zmuda

Isabella Reed

Abby Davidson

Upcoming Events

Related News

Jump to Section

Introduction

The recently enacted legislation, H.R. 1, also known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, and President Trump's Fiscal Year (FY) 2026 budget request signal significant changes to the federal, state and local government partnership. While counties collaborate with federal and state partners to deliver essential services, several changes — aimed at reducing federal costs — will shift financial and administrative costs onto subnational levels of government. In a complex intergovernmental structure, these subnational governments, including counties, could see a downstream effect approaching $1 trillion over ten years.[1] This removal of longstanding federal funding sources and federal cost shift represents a fundamental swing in the intergovernmental partnership, potentially pushing counties to choose between cutting services or raising local taxes.

To comply with expanded federal mandates and maintain essential services, counties may need to generate additional revenue, potentially shifting billions of dollars in federal costs to local taxpayers.

Counties understand the urgency of restoring long-term fiscal stability. With the federal budget representing roughly one-sixth of the national economy and federal debt exceeding $36 trillion, the current trajectory is unsustainable. County leaders work in lockstep with federal partners and the fiscal commitments in Washington, and we aim to be active partners in advancing both national fiscal responsibility and the immediate needs of our communities—particularly populations that seek support, like older Americans, veterans, families and the youngest members of our communities.

Importantly, counties are economically diverse—one-third are growing, one-third stable and one-third confronting decline. As creations of state governments, all counties must also navigate state mandates, preemptions and revenue constraints. When counties experience cuts to intergovernmental transfers, they are still required to deliver essential services. However, many face state-imposed limits on raising taxes, and overall, counties are operating in a stagnant fiscal environment. A balanced approach to intergovernmental reform must account for this variability and preserve local discretion.

This report outlines how the federal cost shift and spending cuts pose a significant challenge to counties nationwide. It aims to clarify the scope of the potential impact, highlight key areas of concern and provide county leaders with the information needed to prepare for and respond to these intergovernmental changes.

As counties lose forms of federal support and shoulder additional costs, they will need to weigh various tradeoffs and options, including:

- Cut or scale back critical services, including public health, nutrition, emergency response and rural development

- Continue to deliver services at a new cost, given the elimination of funding and statutory requirement to uphold certain services

- Raise local taxes or fees to cover new costs

- Delay or cancel infrastructure and resilience investments

- Absorb long-term economic and social consequences of underfunded programs

Key Takeaways

These federal changes present three distinct challenges for counties: increased costs, diminished federal support and reduced local autonomy. This triad could strain local budgets beyond their capacity, potentially leading to delayed services, workforce reductions or increased local taxes to sustain essential and required operations.[7]

The changes not only place significant fiscal burdens on counties but also reflect reduced authority of local governments as the delivery of federal programs is mandated with stricter requirements but without sufficient financial or technical support.

Increased Costs for Counties

- Counties that are required to contribute to the non-federal share of administration costs for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) may face up to an $850 million increase in annual obligations due to federal cost-sharing reductions from 50% to 25% starting in FY27.[8][2]

- The removal of the 5% Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) incentive for late Medicaid expansion states[11] will cause the cost of future expansion to fall more heavily on the state and local governments, increasing their share of expenses for resident care.

- New federal limits on provider taxes—a critical mechanism states use to finance their Medicaid programs—will increase financial pressure on state budgets, particularly in states that have expanded Medicaid coverage.

- New SNAP and Medicaid work requirements, along with SNAP benefit cost-sharing tied to payment error rates, will increase enrollment verification demands—raising the administrative burden in states where counties administer these programs.

- The uninsured population is estimated to increase by 10 million in 2034 due to changes to Medicaid and ACA policies enacted in OBBBA.[54]

- This reduction in health insurance coverage will strain county-supported health systems, which are required to provide care regardless of insurance status and are already facing budgetary uncertainty as uncompensated care costs rise. This impact will be felt strongest in rural counties, which are projected to lose $155 million in Medicaid spending.

Decreased Intergovernmental Support

- The proposed elimination of programs such as the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG), the Home Investment Partnerships Program (HOME) and the Economic Development Administration (EDA).

- Over $5 billion in proposed cuts to funding would reduce support for rural counties and residents, including significant cuts to the USDA Rural Development program, the elimination of the Economic Development Administration and reduced funding for regional commissions.[5]

- The cancellation of FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program, which if not restored, will leave counties more vulnerable to disasters, removing a key source of federal disaster mitigation funding.

- Following a surge in spending growth during the post-pandemic era—driven by one-time expenditures and surplus funds—state budgets for FY25 experienced an aggregate 6.2% decline in spending levels.[50] General fund spending for FY26 was already projected to level off, with many states prioritizing budget cuts or increasing contributions to rainy-day funds.[51]

- With federal funding cuts, state budgets will be constricted further; to continue funding federal programs and maintain a balanced budget (a requirement in most states), states could limit intergovernmental transfers, the second-largest funding source for counties.

- Medicaid cuts could deeply impact the county workforce and economy on its own: for each $1B annual reduction in Medicaid spending, states could lose anywhere from 8,000 to 18,000 hospital jobs, reducing tax revenue by millions and statewide economic activity by billions over 10 years.[52] On the other hand, tax provisions could lead to a 1.2 percent expansion in the size of the long-run economy.[53]

- Severe budget shortfalls in over 700 rural counties due to a lapse in the reauthorization of the Secure Rural Schools (SRS) program have already resulted in an average funding cut of 80% for counties with federal forests.

- Unpredictable funding for the Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) program, which continues to rely on annual appropriations and risks reverting to pre-2008 levels, strains the ability to provide essential services in counties with large federal landholdings.

Reduced Local Autonomy

- As counties face additional funding constraints, they are less able to prioritize services such as hospitals, parks, libraries, public transit and 911 call centers, all highly valued by residents.

- In many cases, county services are mandated by the state or the federal government — counties cannot simply cut these services if the budget is tight, meaning raising local taxes may be necessary to make up for the increased costs placed on counties.

- New eligibility requirements and more frequent verifications for Medicaid will reduce flexibility for states to determine eligibility and coordinate with counties.

- Counties that administer SNAP and Medicaid will need to expand staffing and invest in new technology to meet the requirements—despite receiving no additional funding to support these efforts.

Section 1

The County Role in the Intergovernmental System

Counties are an essential part of the intergovernmental system in which federal, state and local governments work together to serve residents. As the level of government closest to the people, counties bridge the gap between national policies and local implementation. Counties are responsible for delivering a broad array of services — from infrastructure, public health and emergency response to criminal justice and human services — while simultaneously managing regulatory compliance and balancing diverse local needs.

Counties serve as both administrators of state and federal programs and as autonomous units of local governance, making them indispensable to the efficient functioning of the broader intergovernmental framework.

Counties as Providers of Essential Services

Counties play a vital role in our communities, investing nearly $743 billion in essential services each year.6

Across the nation, counties:

Help veterans access benefits in 29 states and the District of Columbia through County Veteran Service Officers (CVSOs)

Collaborate with federal agencies to deliver service on over 600 million acres of public lands

Support more than 900 hospitals and more than 700 long-term care facilities

Operate 91% of local jails, which processed 7.6 million admissions in 2023 and are major providers of health services, especially behavioral health

Own and maintain 44% of public road miles, 38% of bridges, 40% of transit agencies and 34% of airports

Administer elections through the funding and management of over 100,000 polling places staffed with over 630,000 certified poll workers each election cycle

Manage, fund and operate 7,050 Public Safety Answering Points (PSAPs), call centers that handle emergency calls and coordinate emergency responses

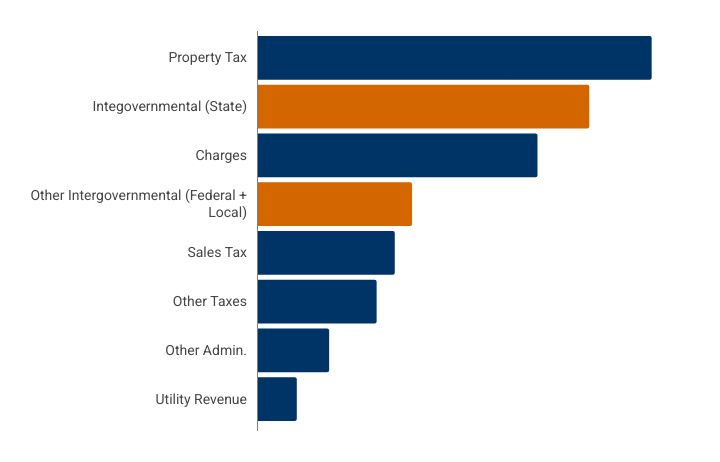

How Counties Are Funded

To provide these essential services, counties rely on revenue generated from taxation, primarily property taxes. Because counties serve as service providers for both state and federal programs while also addressing local priorities, our financial structure often depends on a combination of locally generated revenue and funds allocated from the state and federal governments.

Counties — particularly those in rural areas or with smaller populations — work under tight budget constraints. Therefore, if additional costs are transferred, counties will either pass the costs along through increased taxes for local taxpayers, an action limited by legislation in many states, or reduce essential services. In many states, counties encounter tax caps or cannot levy certain types of taxes, restricting our ability to raise funds.[55]

Furthermore, counties have been operating in a flat fiscal environment over the past five years. When adjusted for inflation, total county revenues decreased from $794 billion in 2017 to $776 billion in 2022—a drop of $18 billion. Despite this decline, counties continue to face rising service demands, inflationary cost pressures and new federal and state mandates. This stagnant revenue trend underscores the need for stable and predictable federal support to help counties fulfill their responsibilities to residents.

Property Taxes Provide Top Source of County Revenue

Source: NACo Analysis of U.S. Census Bureau - 2022 Census of Individual Governments: Finance.

Counties as Administrators of Federal Programs

Counties serve as frontline administrators of many of the nation’s most important federally funded programs, translating national policy into tangible services for residents. As critical partners in implementation, counties bridge the gap between federal mandates and local needs, often as required by frameworks established by state legislatures.

While federal and state governments often design public programs, counties are the primary delivery agents, ensuring that services reach communities effectively.

Through managing major federal programs like Medicaid, SNAP, PILT and SRS, counties deliver vital support to our residents and businesses at the local level. Counties’ significant role in this dynamic partnership ensures that federal initiatives are effectively tailored to the diverse needs of communities nationwide. This essential role highlights the critical function of counties in implementing national priorities while also exposing them to increased risk when federal cost-sharing structures change.

Section 2

Fundamental Changes in Direct Federal Funds to Counties

Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) and Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Funding

Does your county receive PILT or SRS? The funding may be reduced.

Sixty-two percent of counties have federally owned land within our boundaries. Local governments cannot tax property values or products derived from federal lands. The Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) program currently compensates counties with federal lands for lost property tax revenue. Public lands counties rely on PILT to provide critical services like infrastructure maintenance, clean water delivery and law enforcement to residents and visitors alike; however, PILT payments have not kept pace with local expenditures for community service delivery.[13] Without mandatory funding, PILT remains subject to the annual appropriations process and may return to pre-2008 funding levels, potentially compromising essential local services in counties with large federal landholdings.

Without predictable mandatory funding, PILT will remain a discretionary program subject to the annual appropriations process and could fall back to pre-2008 funding levels.

Furthermore, the Secure Rural Schools (SRS) program has not been formally reauthorized as of July 7, 2025 for FY24. SRS was enacted in 2000 to stabilize payments to rural counties and school districts affected by the decline in revenue from timber harvests on federal lands. Barring a long-term solution, SRS will continue to be subject to the annual appropriations cycle, and its lapse has already created dramatic budgetary shortfalls for over 700 rural counties. The uncertainty of these funding streams is a significant challenge for counties that rely on these programs to fund essential education services, roads, conservation projects, search-and-rescue missions and fire prevention programs on a limited tax base.

Program Administration Funding

Counties play a key role in financing and administering programs in partnership with federal and state governments. Prime examples of this intergovernmental partnership include health care and nutrition assistance programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid, for which many counties contribute to the non-federal share of costs.

H.R. 1 (One Big Beautiful Bill Act) introduces shifts of administration costs toward states, and thus counties in several states where counties administer programs and/or are responsible for some or all of the non-federal share. Furthermore, counties are not able to opt into federal programs such as SNAP and Medicaid and thus must continue to deliver administrative services as determined by state law; in some states, counties have a mandate to cover the administrative and care costs of Medicaid. Counties may be forced to weigh raising taxes against reducing services while adapting to evolving state and federal mandates to continue effectively serving our communities.

In at least 9 states, counties are responsible for Medicaid and/or SNAP delivery, including eligibility requirements, enrollment and renewals.

In addition, H.R. 1 (One Big Beautiful Bill Act) increases eligibility verification requirements for SNAP and Medicaid – a cost that will ultimately fall onto counties that administer the program. For Medicaid, increasing eligibility verification from once to twice per year is essentially doubling the workload for counties and will require additional staff or resources. For example, St. Louis County, Minn. estimated that the county will incur an additional cost of over $10 million for SNAP and $6.4 million for Medicaid. If the county were to afford these additional costs through property tax increases, that would be the equivalent of a 9.5% increase in property tax levy.[60]

Does your county administer or contribute to a federal program, like SNAP or Medicaid?

In 10 states, counties administer SNAP

Medicaid Contribution Mandates for Counties

Identifies if counties within a state contribute to Medicaid and associated state mandates. Source: NACo Research, 2023.

Medicaid

County Role

Counties contribute significantly to the current non-federal share of Medicaid — up to $7.6 billion annually in states like New York.[15] They also play a role in administering the program in at least nine states.

Cost Shift

Late expansion states (states that expand Medicaid after January 1, 2026) will no longer receive the additional 5% federal funding incentive, so the cost of the expansion will fall more heavily on the state and local governments. Furthermore, states will face new limits on provider taxes—a critical mechanism states use to finance their Medicaid programs.

Administrative Burden

Other mandates, such as more frequent eligibility verification, place a further financial burden on counties, which already must adhere to complex and varying requirements set by each state. These administrative changes can also risk delays or loss of care for residents, 92% of whom are working full-time, part-time or have a qualifying exemption such as caregiving responsibilities, disability or school attendance.[59]

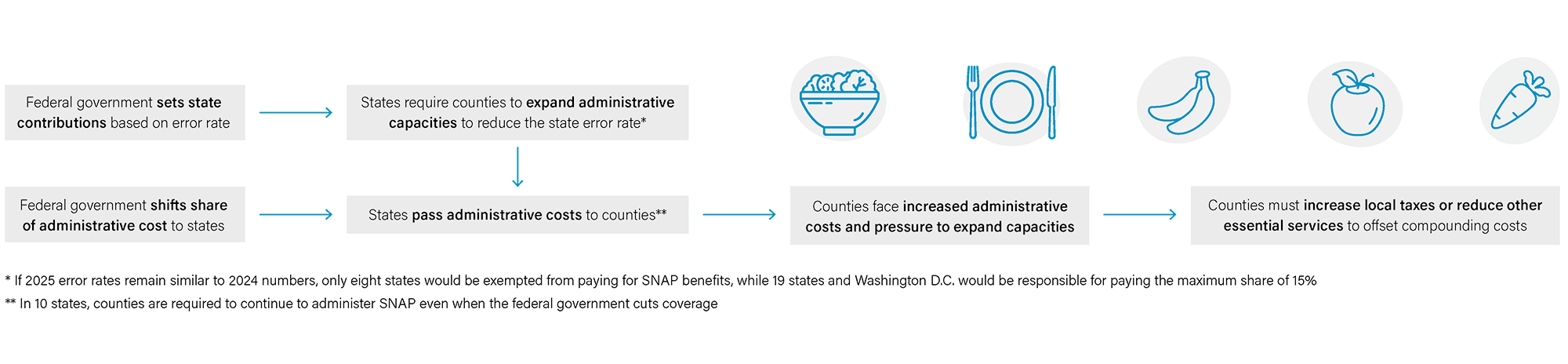

SNAP

County Role

Counties administer the program in 10 states, representing 34.3% of the total participants, or 14.6 million people.[16]

Cost Shift

The state and county administrative cost share will increase from 50 to 75% beginning in FY 2027. Counties may face up to $850 million in added administrative costs, ranging from $19 million in Virginia and $96 million in North Carolina to $247 million in California and $266 million in New York.[17] [18] [61]

Administrative Burden

Other mandates, such as expanded work requirements and benefit cost-shares being contingent on error rates, increase the workload in counties, which already have strained human resource staffing.[56]

Changes to SNAP at the federal level will flow to county governments

Local Program Support

Many counties rely on federal grants to fund and administer critical operations and public services such as safety net programs, like Medicaid, SNAP and TANF, as well as community development programs, climate resilience and other specialized needs. Counties also receive direct federal transfers through the Infrastructure and Investment Jobs Act (IIJA) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to upgrade critical infrastructure, including roads, transit and airports. Together, these federal grants support counties as we administer programs, provide services and coordinate action among local stakeholders. The loss of this funding could squeeze counties financially and force local governments to find new revenue sources to fund these important programs, severely downsize them or eliminate them entirely.

Does your county receive funding from federal programs? See the status of program funding here.

Some of the proposed cuts in the President’s FY 2026 budget include:

(see NACo’s Analysis of FY 2026 President’s Budget to view the full breakdown)

- Eliminates funding for essential housing programs such as the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG), the HOME Investment Partnerships Program (HOME) and the Pathways to Removing Obstacles (PRO) Housing program

- Ends $291 million in discretionary awards for the Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund, limiting communities’ ability to expand access to capital, support small businesses and drive local economic growth

- Reduces the Clean and Drinking Water State Revolving Loan Funds and Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) program, which would impact counties’ ability to maintain and improve water infrastructure without raising rates for residents. West Virginia, for example, is facing a proposal that would cut federal funding for these programs by 89%[19]

- Reduces funding of the Army Corps of Engineers by 20% from FY 2025, which would limit the assistance provided by the Army Corps to protect, maintain and develop water infrastructure systems while advancing county interests related to ports, inland waterways, levees, dams, wetlands, watersheds and coastal restoration

- Reduces the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) budget by 40% from $28 million to $17 million, affecting election administration in counties

- Decreases Forest Service funding from $16.8 billion to $4 billion, affecting programs related to wildfire mitigation, forest health, recreation access and watershed protection

- Eliminates the Economic Development Administration, which helps counties invest in infrastructure, workforce development and small business support to help bolster local economic prosperity and resilience

- Cuts to the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Brownfields program, which helps counties clean up and redevelop contaminated parcels of land to create new economic development opportunities for residents

- Cuts $491 million from the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, or about 17% of operational funds, which impacts technical services provided to state and local governments through programs like the Multi-State/ Elections Infrastructure Information Sharing and Analysis Center (MS/ EI-ISAC)

Billions in funding for rural counties and residents at risk

Over $5 billion in funding that supports rural counties and residents is also at risk if Congress adheres to the President's FY 2026 budget request, which advises significant cuts to the USDA Rural Development program, the elimination of the Economic Development Administration and reduced funding for regional commissions.[20] Farmers and foresters will also face funding challenges related to natural disasters, natural resources and economic support if the $15 billion in proposed cuts to the Forest Service and the Farm Service Agency take place.

These cuts will undoubtedly affect county government services and operations. Concurrently, counties will experience some budget increases, primarily for transportation and infrastructure programs, such as $824 million for Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) upgrades at airports — including county-owned airports — across the country.

County Spotlights

Pitkin County, Colorado

Home to the White River National Forest, Pitkin County is hiring additional backcountry community response officers to support the Forest Service after staff shortages left the forest without enforcement.

White River is one of the most visited national forests in the nation, but staffing shortages at the Forest Service resulted in only one enforcement officer being assigned to cover 2.3 million acres.[23] The county is now providing staff to serve locals and visitors to the forest, including recreation management, public safety, resource protection and visitor experience. Public safety is a critical component of county operations, including search-and-rescue missions in the backcountry. The county is assuming this additional responsibility to provide essential services for the community as federal support wanes.

“Since January I have lost 38% of my permanent staff across nearly every department on the Aspen-Sopris Ranger District, and I am not able to hire our normal summer seasonal staff. The services provided to the public by Forest Service employees will not be the same, and reductions in services will be felt in fire prevention, visitor information, trail maintenance, remote restroom cleaning, and many other facets of forest management.”

— District Ranger, Aspen Sopris Ranger District

Washoe County, Nevada

Like many jurisdictions throughout the U.S., Washoe County is facing high housing costs and a homelessness crisis. Across the state of Nevada, more than 10,000 people experienced homelessness in 2024, a 17% increase from the year before.[24]

Proposed cuts to the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) could have serious consequences for counties in Nevada and the populations experiencing homelessness. Washoe County received $3.2 million through the Continuum of Care program, which is subject to budget cuts.[25] This funding is used by county agencies to provide rental assistance and supportive services for people experiencing homelessness. In addition, reducing housing assistance, such as Housing Choice Vouchers, can undermine the ability of county residents to pay rent.

“All the people in that program were previously experiencing homelessness. The vast majority of those folks would return to homelessness if it were not for these voucher resources.”

— Homeless Services Coordinator, Washoe County[26]

Lane County, Oregon

In this western Oregon county, officials have become increasingly concerned in recent years about wildfires breaking out in its vast swaths of rural, forested land. The county had planned to use a $19.6 million federal grant from the Inflation Reduction Act, awarded last July, to create a network of six hubs to support residents during natural disasters.[21] The cancellation of this grant represents a setback for its efforts to manage wildfire risk.

“We’re profoundly disappointed with this outcome, and this is a really important grant for Lane County. We’ve lost over 700 square miles of Lane County to wildfire in the last five years. We have a deep need for sheltered space that can be air conditioned, air filtered and even during winter storms — heated, and that’s what this grant would have provided for us in six distinct locations.”[22]

— Policy Director, Lane County

Miami-Dade County, Florida

Miami-Dade County, home to over 2.7 million residents, predicts that it may need to find alternative funding sources to replace up to $350 million in federal grant funding that is proposed to be cut in the President's FY26 budget. The impact would be especially severe in county programs that derive a majority of their funding from federal agency grants, including ones in housing, community development and the county’s Homeless Trust. Potential cuts also challenge the county’s investments in climate adaptation and infrastructure improvement, increasing its vulnerability to extreme weather and natural disasters. These risks come on the heels of existing federal funding freezes that have adversely affected local initiatives such as HIV/AIDS prevention, disaster recovery and community food banks. The county faces significant reduction or elimination of critical public services, including:

- The Reconnecting Communities Program under HUD: up to $17 million

- Head Start: up to $88.8 million serving over 7,500 children and families

- Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers: $64.7 million serving over 5,400 low-income households

- LIHEAP: up to $11 million

- Homeless Trust: up to $54.3 million

Section 3

Response in Crisis: Federal Reforms and the Rising Disaster Cost Burdens on Counties

Is your county eligible for disaster response funding through an emergency declaration? That funding may be at risk.

Rising Disaster Costs for Counties

Every county nationwide has experienced at least one federally declared major disaster in the last 25 years.[49] Whether it’s a flood, wildfire, hurricane, or winter storm, the data suggests that many counties will face a disaster at some point, highlighting the importance of sustained investments and reliable intergovernmental partnerships in preparedness, resilience and recovery.

In 2024, 1,207 counties experienced at least one federally declared disaster.[27]

Every County has Experienced a Federally Declared Disaster

Number of Federally Declared Disasters: 2000 to 2024

Counties are vital in the national emergency management system, participating in every phase — from planning and preparation to response and recovery. Nationwide, counties allocate billions to developing emergency plans, ensuring coordinated communication, providing emergency health services, implementing mitigation strategies and leading both short-term and long-term recovery efforts. In times of unexpected and life-threatening disasters, counties are often first to respond and last to remain, continuing recovery efforts long after federal and state partners have left.

Over the past two decades, natural disasters have increased in frequency, severity and cost. In 2024, there were 27 separate billion-dollar disasters, totaling $182.7 billion in damages, almost double the $95.3 billion in damages in 2023.[29] Each year, nearly 900 counties — almost one-third of the nation’s total — experience at least one federally declared disaster.[30] Counties make critical disaster recovery investments well before federal assistance becomes available and are left to navigate the complex and lengthy federal disaster funding process on top of continuing to provide support for their community.

Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Number and Combined Cost of Disasters

Source: NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters, (June 2025).

Policy Shifts and Executive Orders That Reduce Local Support

Recent executive orders, federal funding terminations and discussions about disaster management reforms are likely to change FEMA’s interaction with local governments in ways that increase local fiscal pressure and elevate financial risk.

Recent developments in disaster response that will impact counties include:

- Growing trend in policy proposals toward shifting disaster preparedness and response responsibilities to local governments, often without providing adequate resources or support.[31]

- Cancellation of FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC). Established under the 2018 Disaster Recovery Reform Act, BRIC provided $750 million to $1 billion annually for projects like stormwater systems, wildfire prevention and flood protection. With BRIC’s termination:

- Counties lose a primary, dedicated source of pre-disaster mitigation funding.

- All applications from FY 2020–FY 2023 were canceled, and FY 2024 funding was withdrawn, halting ongoing and planned mitigation efforts.

- Counties must now depend more on limited state or local resources, which may not be sufficient to meet growing hazard mitigation needs.

The potential impacts of proposed funding cuts are especially acute in rural and fiscally constrained counties, which often lack the reserves or borrowing capabilities to respond to large-scale emergencies effectively.[32] [33] This creates a compounding cycle: insufficient pre-disaster investment leads to delayed post-disaster recovery and limited long-term resilience.

Proposed Reforms Aim to Alleviate County Financial Strain

FEMA’s Public Assistance program is a vital post-disaster funding tool, reimbursing eligible governments and nonprofits for response and recovery. The program requires counties to front disaster costs — often using reserves, borrowing or diverting funds from other services — which can strain local budgets and delay recovery.[36] A recent NACo survey found that 24% of counties reported significant cash flow issues due to delayed FEMA reimbursements.[37]

To address these challenges, the draft bipartisan FEMA Act of 2025 proposes key reforms, such as shifting reimbursements to funding through direct grants and streamlining permitting and review processes. These changes aim to improve funding timeliness and strengthen counties’ financial capacity to effectively manage disaster response and recovery.

Reforms like these exemplify the strength of intergovernmental partnership in action. Counties are also continuing to advocate for a meaningful role in pre-disaster preparedness efforts. By doing so, counties aim to help shape disaster policies that are both informed and comprehensive — reforms that not only function within but also enhance the broader intergovernmental framework.

County Spotlights

Jefferson County, Kentucky

The loss of BRIC funding will directly impact the metropolitan government of Louisville-Jefferson County. Following a historic flood event, the county planned to upgrade its 70-year-old flood infrastructure. This improvement would focus on the West Woods Creek Basin and the Western Flood Pump Station, which help protect over 200,000 people, nearly 80,000 structures and billions of dollars’ worth of property from flooding.[38] Without federal funding, the city-county government is forced to shift the cost of this critical infrastructure into its budget and hopes to find a creative solution in state or federal funding to finance the infrastructure project without increasing the burden on taxpayers.

Charlotte County, Florida

Charlotte County, where Hurricanes Milton and Helene made landfall in the fall of 2024, is still reeling from the financial devastation caused by Hurricane Ian in 2022. The estimated cost of Hurricane Ian exceeds $362 million. After receiving reimbursements from FEMA, state and granting agencies, insurance and the Florida disaster program, the county will have a nearly $27 million shortfall.[39] As of August 2024, the county had only received about 20% of the FEMA reimbursements for Hurricane Ian.[40] The pace of the remainder of the reimbursement for Hurricane Ian and the estimated amounts for Hurricanes Milton and Helene will impact how the county funds repairs to essential infrastructure such as roads, bridges and water control facilities.

Section 4

Strains on the County-Delivered Safety Net System

Indigent and Uncompensated Care

Medicaid operates and is jointly financed and administered as a partnership between federal, state and local governments. Counties nationwide often deliver Medicaid-eligible services and in many cases help states finance the non-federal match and administrative costs. Many county residents maintain their health through public health care programs, utilizing approximately $1.59 trillion in medical care benefits, including Medicare, public assistance medical care and military medical insurance, and $721 billion in Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) benefits.

As frontline health care providers, counties fund and operate hundreds of hospitals, nursing homes, behavioral health authorities, and local health departments. Without access to adequate health care coverage through Medicaid or other options, individuals still seek care — often in county-funded emergency rooms or clinics — resulting in higher levels of uncompensated (when no payment is received) and indigent care (offered free or at reduced rates). Counties also shoulder the full cost of healthcare for individuals in local jails awaiting trial who would otherwise be eligible for federal benefits. Regardless of an individual’s insured status, counties serve as the resource of last resort and must be equipped to provide care.

When individuals require care but lack health insurance, counties often absorb the cost of services, from hospitals and emergency rooms to long-term care facilities.

The changes to Medicaid coverage enacted in H.R. 1 (One Big Beautiful Bill Act) will directly impact county budgets through uncompensated care. It introduces new work requirements, requires more frequent eligibility verification, and introduces out-of-pocket costs for some low-income enrollees. It also reduces federal matching dollars for emergency services provided to certain non-lawful immigrants in the expansion population. These changes are projected to increase the number of uninsured people by over 10 million people by 2034[57], which would increase uncompensated care costs for counties by shifting the financial burden to local hospitals and health care systems.[58]

These impacts have a ripple effect - as more residents forgo routine or preventive care, demand for uncompensated emergency services is likely to grow, straining local providers, increasing county fiscal burdens and potentially impacting taxpayers[42] For example, Florida counties use indigent care and trauma surtaxes to support healthcare for uninsured residents.[44]

Counties Play an Essential Role in Protecting, Promoting and Improving the Health of Communities Across the Nation

533K

hospital and health care workers

Counties employ over 533,000 hospital and health care workers

900

hospitals

Counties support more than 900 hospitals that provide inpatient medical care and specialized care

700

long-term care facilities

Counties also own and support more than 700 long-term care facilities

Rural Hospitals and Emergency Services

Increases in health care costs often impact rural counties the most. Over 46 million people, or 15% of the U.S. population, live in rural areas, where they face higher disparities in chronic diseases and increased mortality from preventable causes. Rural communities experience provider shortages, health care facility closures and long travel times for care, making local health services increasingly critical. Residents depend significantly on Medicaid, which covers about 20% of inpatient discharges and nearly 50% of all births in these rural areas.[48]

Counties play a vital role in strengthening rural health services, with 61% of local health departments serving rural areas. Despite this, many rural hospitals struggle with persistent financial challenges. Since 2005, 146 rural hospitals have either closed or ceased offering inpatient services. Between 2017 and 2021, 71% of hospitals experiencing financial decline were located in rural areas, and 612 of those were operated by state and local governments.[45]

To reduce the risk to rural hospital closures resulting from Medicaid cuts, H.R. 1 (One Big Beautiful Bill Act) includes a new Rural Health Transformation Program funded with $50 billion from FY 2028 to FY 2032 to support state efforts to strengthen rural hospitals and health providers. Funds must not be used for Medicaid cost-sharing; rather, states are required to submit transformation plans outlining strategies to improve outcomes, expand access and stabilize hospital finances. Although this program will provide assistance to rural healthcare, it will not cover the full $155 billion reduction in federal Medicaid spending in rural areas.[46] This lack in federal support will strain county hospitals and the ability of rural counties to serve their residents.

Increased strains on county budgets could also limit the ability to provide emergency medical services (EMS). Rural counties are more likely than urban counties to have ambulance deserts, where the nearest ambulance station is sometimes more than 25 minutes away.[47]

Conclusion

H.R. 1, also known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, and the President’s FY 2026 budget request contain changes that could significantly shift costs to counties, imposing new financial burdens, reducing local autonomy and straining essential services. As an integral partner in the intergovernmental system, we aim to work across all levels of government to find fiscally responsible solutions while ensuring our communities remain safe and healthy. Substantial cost shifts will require conversation and coordination.

Reductions in direct federal funding have already led to an 80% decrease in payments to federally forested counties and will shift millions in administrative SNAP costs to counties that contribute to the non-federal share. Medicaid changes are particularly significant, potentially increasing uncompensated care costs and compounding the burden on county hospitals by leaving millions without coverage.

Further cuts requested include reductions in rural development funding, the elimination of the Economic Development Administration and the cancellation of FEMA’s BRIC program, all of which diminish counties’ capacity to support local economies and prepare for disasters. These reductions shift federal responsibilities without providing counties with the authority or resources to manage them, leading to stark choices: reduce or delay services, raise local taxes or both. In many cases, counties are mandated to provide services without the flexibility to opt out.

Counties serve as frontline implementers of federal and state programs — from health and human services to infrastructure, disaster response and economic development. Additional risks to counties’ fiscal stability could undercut the ability to serve residents and uphold mandates. Protecting counties from unfunded federal cost shifts is not only about preserving local budgets but also safeguarding the essential services that millions of Americans rely on daily.

Appendix

Data Tables

Table I: Service Categories by State

Table II: SNAP Error Rate Table

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture

Authors

Teryn Zmuda

Isabella Reed

Abby Davidson

Stacy Nakintu

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Ricardo Aguilar and Chris Campbell for their significant contributions and to the counties that shared their insights for this report.

Endnotes

[1] The exact downstream fiscal impacts of the federal cost reductions will not be known for years. Initial calculations estimate cuts of $1 trillion to Medicaid and $186 billion to SNAP, an additional $283 billion in uncompensated care sought by the newly uninsured, and billions in cuts to grants, programs, and departments that serve local government and residents as proposed in the President's FY26 budget request. The compounding effects of these reductions will largely fall on county governments, given the nature of services provided at the subnational and county level.

[2] Cortina, Julia, “Federal Reforms to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): What Counties Should Know” (Washington, D.C.: National Association of Counties (NACo), 2025).

[3] Congressional Budget Office. ”Estimated Effects on the Number of Uninsured People in 2034 Resulting From Policies Incorporated Within CBO’s Baseline Projections and H.R. 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.” (Washington, D.C.: CBO, 2025)

[4] Ibid.

[5] NACo, “Analysis of FY 2026 President’s Budget" (2025).

[6] NACo, “The County Landscape Project: Maps and Stats" (2025).

[7] Many county services are mandated by the states or the federal government — from activities in criminal justice and public safety, health and human services, transportation and infrastructure, to administration of elections and property assessments — counties cannot simply cut these services if the budget is tight.

[8] For example, in Scioto County, Ohio, the county is solely responsible for administering SNAP to nearly 24% of the county population.

[9] For example, for FY 2023, the federal share of Medicaid was 69%. The other 31% is paid for by a variety of other sources, including local governments. Through the Secure Rural Schools program, the federal government provides critical support for counties affected by the decline in revenue from timber harvests on federal lands to fund schools and roads, among other services.

[10] For example, the Illinois Governor’s office is projecting state revenues to come in about a half-billion dollars below the baseline projections previously assumed; in Alabama, SNAP funding changes could cost the state $115 million to $120 million in General Fund money to maintain the program, risking other areas of the budget.

[11] To see which states have already expanded, see “Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions” by KFF (May 9, 2025)

[12] Blavin, Fredric, Matthew Buettgens and Michael Simpson, “Health Care Providers Would Experience Significant Revenue Losses and Uncompensated Care Increases in the Face of Reduced Federal Support for Medicaid Expansion” (Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute, 2025).

[13] Reed, Isabella, Teryn Zmuda and Gregory Nelson, “A Split Story: Economic Trends in Public Lands Counties” (Washington, D.C.: NACo, 2025).

[14] States in which counties are mandated to contribute to Medicaid: California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, New Hampshire, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida

[15] Nineteen states mandate counties to contribute to the non-federal share of Medicaid costs and/or administrative, program, physical health and behavioral health costs, and six counties do so without such a mandate.

[16] Cortina, Julia, “Federal Reforms to Social Safety Net Programs: What Counties Should Know” (Washington, D.C.: NACo, 2025).

[17] Ibid.

[18] See table 1

[19] Elbeshbishi, Sarah, “Trump administration proposal would cut nearly 90% of federal funding to West Virginia water and sewer programs” Mountain State Spotlight, June 6, 2025, available at https://mountainstatespotlight.org/2025/06/06/donald-trump-water-funding-cuts/ (June 30, 2025).

[20] NACo, “Analysis of FY 2026 President’s Budget” (2025).

[21] Samoya, Monica, “Trump administration guts federal funds that would have helped Lane County weather major disasters” OPB, May 6, 2025, available at https://www.opb.org/article/2025/05/06/trump-administration-guts-federal-funds-to-help-lane-county-weather-major-disasters/ (June 30, 2025).

[22] Ibid.

[23] Stingray, River, “Pitkin County’s U.S. Forest Service funding ‘just isn’t going to cut it’” The Aspen Times, May 7, 2025, available at https://www.aspentimes.com/news/pitkin-countys-u-s-forest-service-funding-just-isnt-going-to-cut-it/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CIt%27s%20possible%20adding%20two%20people,to%20this%20and%20play%20ball.%E2%80%9D (June 30, 2025).

[24] Lyle, Michael, “Nevada homelessness, housing crisis will only get worse under Trump budget plans, providers warn” Nevada Current, May 19, 2025, available at https://nevadacurrent.com/2025/05/19/nevada-homelessness-housing-crisis-will-only-get-worse-under-trump-budget-plans-providers-warn/ (June 30, 2025).

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] These figures reflect the number of major and emergency disaster declarations issued for incidents affecting counties nationwide. A major disaster declaration is issued by the President for events that exceed the capacity of state and local governments to respond, typically due to the severity of a natural or man-made incident. This designation unlocks a broad range of federal assistance for individuals and public infrastructure. In contrast, an emergency declaration is issued when federal assistance is needed to support state, local or tribal efforts, usually for more limited events. Assistance provided under an emergency declaration is typically capped at $5 million.

[28] Chen, Gang, “Natural Disasters and the Fiscal Sustainability of Local Governments,” Public Budgeting & Finance, 39 (1) (2019): 24–46.

[29] NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, “Billion-dollar weather and climate disasters: Overview” (2025).

[30] NACo Analysis of the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Disaster Incident data, 2024.

[31] Executive Office of the President, Executive Order 14239: Achieving Efficiency Through State and Local Preparedness (The White House, 2025).

[32] Chen’s 2019 study on the fiscal impacts of natural disasters finds that disaster-affected counties significantly increased their long-term debt burdens, particularly when disaster costs were high and federal reimbursements were delayed. The analysis highlights how such debt accumulation reduces future budget flexibility and imposes lasting constraints on local governments' fiscal health.

[33] Chen, Gang, “Natural Disasters and the Fiscal Sustainability of Local Governments,” Public Budgeting & Finance, 39 (1) (2019): 24–46.

[34] Yuan, Jiqiu and Christine Cube, “Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves: 2019 Report” (Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Building Sciences, 2019).

[35] Ibid.

[36] Shrawder, Kevin and Brett Mattson, “Counting the Costs of Post-Disaster Reimbursement: County Fiscal Impacts of Federal Disaster Response” (Washington, D.C.: NACo, 2023).

[37] Ibid.

[38] Moran, Meredith, “Counties scramble after FEMA scraps disaster mitigation funds” County News, April 28, 2025, available at https://www.naco.org/news/counties-scramble-after-fema-scraps-disaster-mitigation-funds#:~:text=Following%20the%20cancellation%20of%20a,projects%20on%20a%20smaller%20scal (June 30, 2025).

[39] Semon, Nancy, “Charlotte County projects $362M cost from Hurricane Ian” Gulfshore Business, January 6, 2025, available at https://www.gulfshorebusiness.com/charlotte-county-projects-362m-cost-from-hurricane-ian/ (June 30, 2025).

[40] Semon, Nancy, “Hurricane Ian’s financial impact on Charlotte County still being tallied” Gulfshore Business, January 6, 2025, available at https://www.gulfshorebusiness.com/charlotte-county-projects-362m-cost-from-hurricane-ian/ (June 30, 2025).

[41] Congressional Budget Office. ”Estimated Effects on the Number of Uninsured People in 2034 Resulting From Policies Incorporated Within CBO’s Baseline Projections and H.R. 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.” (Washington, D.C.: CBO, 2025)

[42] Tharpe, Wesley, “Tracking Senate Action on Tax and Budget Reconciliation Plan” (Washington, D.C.: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2025).

[44] Florida Economic and Demographic Research, “2023 Local Discretionary Sales Surtax Rates in Florida's Counties” (2023).

[45] Bryant, Blaire, “Enhance Funding for Local Rural Health Programs” (Washington, D.C.: NACo, 2025).

[46] Saunders, Heather, Alice Burns and Zachary Levinson, “How Might Federal Medicaid Cuts in the Senate-Passed Reconciliation Bill Affect Rural Areas?” (Washington, D.C.: KFF, 2025).

[47] Hart, Owen, “Support Rural Emergency Medical Services” (Washington, D.C.: NACo, 2025).

[48] Euhus, Rhiannon and others, “5 Key Facts About Medicaid Coverage for People Living in Rural Areas” (Washington, D.C.: KFF, 2025).

[49] This excludes COVID-19 related disasters.

[50] National Association of State Budget Officers. "The Fiscal Survey of States" (Washington, D.C.: NASBO, 2024).

[51] National Association of State Budget Officers. "The Fiscal Survey of States" (Washington, D.C.: NASBO, 2025).

[52] American Hospital Association. "Medicaid Spending Reductions Would Lead to Losses in Jobs, Economic Activity and Tax Revenue for States" (Washington, D.C.: AHA, 2025).

[53] Watson, Garrett. "FAQ: The One Big Beautiful Bill Act Tax Changes" (Washington, D.C.: Tax Foundation, 2025).

[54] Congressional Budget Office. "Estimated Budgetary Effects of Public Law 119-21, to Provide for Reconciliation Pursuant to Title II of H. Con. Res. 14, Relative to CBO’s January 2025 Baseline" (Washington, D.C." CBO, 2025).

[55] In forty-two states, counties are somewhat, very, or completely restricted in authority over county finances.

[56] The One Big Beautiful Bill Act changes to the SNAP benefit cost shares for states beginning in FY28 based on error rate: below 6 percent error rate, 0 percent match; 6 percent–8 percent, 5 percent match; 8 percent–10 percent, 10 percent match; Over 10 percent: 15 percent match.

[57] Congressional Budget Office. "Estimated Budgetary Effects of Public Law 119-21, to Provide for Reconciliation Pursuant to Title II of H. Con. Res. 14, Relative to CBO’s January 2025 Baseline" (Washington, D.C.: CBO, 2025).

[58] Other provisions directly tied to the OBBBA, such as the expiration of the expanded premium tax credit and implementing the proposed rule for marketplaces, would increase the uninsured rate by another 5.1 million according to CBO.

[59] Tolbert, Jennifer and others. "Understanding the Intersection of Medicaid and Work: An Update" (Washington, D.C.: KFF, 2025)

[60] Gray, Callan. "Minnesota counties expect Medicaid, SNAP changes could result in tax increase" KSTP, July 3, 2025, available at https://kstp.com/kstp-news/top-news/minnesota-counties-expect-medicaid-snap-changes-could-result-in-tax-increase/ (August 14, 2025).

[61] Of note, H.R. 1 eliminates the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-Ed), a federally funded grant program that served as a mechanism for helping Americans achieve nutrition security, by the end of September 2025, . The end of this program will likely cause the SNAP administrative cost shifts to be lower than originally estimated.