Shelby County engages youth for better mental health services

Author

Upcoming Events

Related News

Key Takeaways

The mental health crisis among youth in the United States has reached alarming levels, with one in five adolescents experiencing a mental health disorder each year. Shelby County, Tenn. is no exception.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the county’s youth coalition became increasingly vocal about the worsening mental health situation and the lack of accessible supportive services.

The coalition proposed the Shelby County Commission use American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding to support youth mental health. They explained that mental health services were far less accessible than leaders thought.

Shelby County, where 25% of individuals live below the poverty line, faces significant challenges with many young people uninsured or struggling to navigate the health care system even when insured.

The commission allocated $1 million to support youth mental health. They invited the youth coalition members to the table to discuss the proposal and co-design the necessary resources to better connect youth with mental health services.

Dorcas Young Griffin, formerly the director of community services, underscored the importance of a collaborative approach. Griffin worked with the youth coalition to integrate the proposal with government systems to effectively use the funding to provide free youth mental health services. This process involved extensive planning and building an infrastructure to increase the number of therapists available to serve youth.

This effort involved reaching beyond the typical community safety net providers, building capacity and relationships with Medicaid and state funding sources to offer mental health services for free. The goal was to alleviate the burden on both therapists and youth navigating the complex Medicaid system.

The program, designed to be part of the Shelby County Youth & Family Resource Center (YFRC), acknowledged that merely establishing services would not ensure their use. Authentic youth engagement was crucial to determine the types of services needed to build the Youth Connect Program.

Kache Brooks, the youth mental health coordinator, spearheaded a multifaceted approach involving surveys and focus groups, gathering data from more than 150 Shelby County young people. This data identified barriers and stigmas preventing youth from seeking mental health care, their priorities in choosing a therapist, and their preferences for therapy modalities — whether group or individual.

Using QR codes, the survey was distributed in schools, youth-serving organizations and during youth gatherings in after-school programs, athletics and faith-based organizations. County staff also identified youth mental health deserts by analyzing the ZIP codes of current providers to pinpoint areas with limited or no access to services to ensure youth input was genuinely reflective of the most in-need youth. Identifying these ZIP codes was a pivotal research step as these locations were later used to determine the target locations to begin Youth Connect services.

Key themes emerged from these engagements: Agency, support, stigma and therapy format. Notably, 48% of youth emphasized the importance of choosing their therapist, prioritizing qualities like gender, ethnicity, lived experiences, age and communication accessibility. In response, the county established a public-private partnership with the Braid Foundation, which vets therapists and matches them with youth based on their specific needs. They also built a webpage with video introductions and bios to help youth choose their therapists.

“It’s not about token involvement,” Griffin noted. “You’re not just here because we need to check a box... there’s planning, and then there’s planning within the plans for young people. When they are coming in and deciding what they need. It’s done in coordination with the young person.”

Support from friends and family also emerged as a vital component of effective mental health services, requiring a nuanced approach that balanced autonomy with meaningful connections. Contrary to the assumptions of resource center staff, 72% of youth reported they would not be embarrassed if their family or friends knew they were in therapy. Additionally, 69% preferred individual therapy, and 73% favored in-office sessions over virtual or community center options.

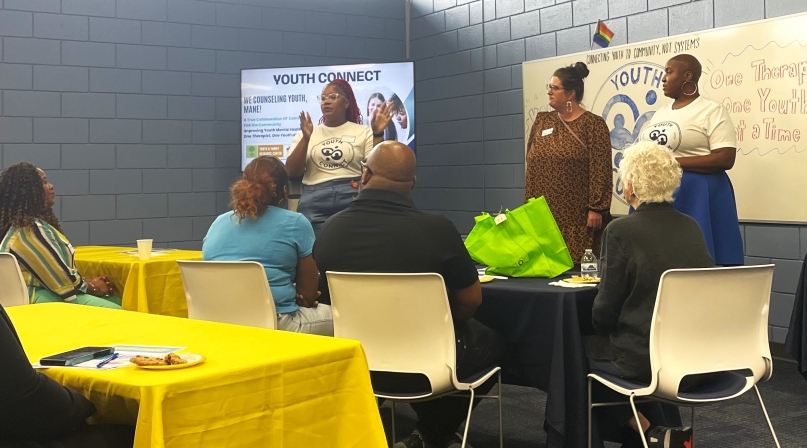

Launching Youth Connect on May 31, Amy Kalb, the Youth and Family Resource Center director, discussed how they will continue to prioritize youth engagement. “We will be [using] post-session surveys to ensure that services are accessible and meet the expectations of the youth,” she said. “These surveys will also track improvements in mental health, correlated with therapy sessions.”

Shelby County’s commitment to authentic youth engagement in mental health service design stands as a crucial example for counties. By involving young people directly, they ensure that services are not only relevant and effective but also sustainable in addressing the mental health needs of future generations.

County News

Tackling youth mental health: Local and national strategies for change

Douglas County, Neb.’s “Here For You, For Them” is an initiative focused on mental health awareness and suicide prevention among youth, providing resources, support and education to help young people and their families navigate mental health challenges.

Related News

House Agriculture Committee advances 2026 Farm Bill

On March 5, the House Agriculture Committee voted to advance its version of the 2026 Farm Bill.

National Association of Counties Launches Initiative to Strengthen County Human Services Systems

The National Association of Counties (NACo) announces the launch of the Transforming Human Services Initiative, a new effort to help counties modernize benefits administration, integrate service delivery systems and strengthen county capacity to fulfill our responsibility as America’s safety net for children and families.

Congress seeking ‘common-sense solutions’ to unmet mental health needs

Rep. Andrea Salinas (D-Ore.): “Right now, it is too difficult to access providers … and get mental health care in a facility that is the right size and also the appropriate acuity level to meet patients’ needs.”