Advancing Cross-System Partnerships: Leadership Lab Case Studies

Upcoming Events

Related News

Overview

To best address the challenges of individuals that interact with various county services, counties are increasingly looking at the way health, human services and justice entities connect. A critical step towards integration is investing in how data is shared. Cross-sector data that looks beyond one system tells a more complete story of the challenges and opportunities to coordinate care and better direct county resources.

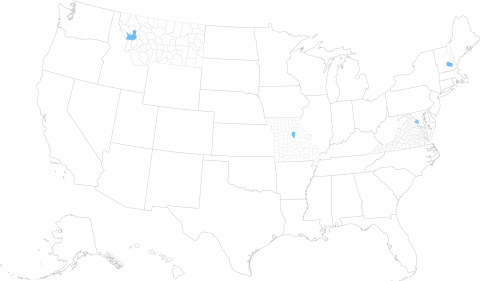

From January 2018 to November 2019, the National Association of Counties (NACo), with support from The Kresge Foundation, brought four counties together through the Advancing Cross-System Partnerships Leadership Lab (Leadership Lab). During the project period, NACo convened and facilitated information exchanges to examine how Leadership Lab counties are working across systems through formalized partnerships and data sharing practices to meet the urgent and complex needs of individuals cycling through health, human services and justice systems. As part of the Leadership Lab, multidisciplinary teams from Boone County, Mo.; Fairfax County, Va.; Merrimack County, N.H.; and Missoula County, Mont., met quarterly to discuss best practices, innovative solutions and continuing challenges. These convenings created an environment for teams to share views on structural frameworks, service models, data management tools and funding streams.

Key Findings

A small cohort allowed for deep engagement, and the locations and size of the communities offered the ability to consider the impact of interventions in diverse settings. Through the work, certain recurrent themes arose, including:

- Cross-systems collaboration requires a deep commitment from every stakeholder.

- Limited access to patient health records (due to HIPAA privacy laws and 42 CFR Part 2 confidentiality agreements) often prevents the full integration of criminal justice, homelessness and health care data.

- County-university partnerships accelerate programming efforts and provide access to more robust resources (i.e. expertise).

Background

In any community, a small number of people frequently cycle through emergency departments, jails and social service systems, which poses a disproportionate burden on these systems. Often, these “frequent utilizers” suffer from serious mental illness, substance use disorders or both — problems that systems are not equipped to appropriately treat independently.

For that reason, looking at the intersection where health, human services and justice systems connect can provide an enduring approach to serving these individuals as well as provide an energetic foundation for corralling diverse stakeholder interests, building strong partnerships and allocating shared or limited resources.

At the intersection of these systems is the data collected from the many agencies serving these vulnerable individuals. With each system capturing information differently, a critical step toward integration is the ability to share data. Systems that work collaboratively to share overlapping client/inmate/patient data offer a better chance of breaking down information silos, preventing the fragmentation of services and promoting a continuity of care — and ultimately, offer a better chance for individuals and communities to thrive.

The following case studies describe how the four Leadership Lab counties leveraged cross-sector partnerships and data-driven processes to meet the complex needs of people who frequently utilize these various systems.

Fairfax County, Virginia

|

Target Population: Adults with mental illness, co-occurring substance use disorders, and those experiencing homeless and/or who have been previously incarcerated Vision: Provide robust wrap-around services, including stable and supportive housing Successes:

Challenges:

|

Fairfax County is a large suburban county located in Northern Virginia, just outside the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. With more than one million residents, Fairfax is Virginia’s most populous jurisdiction. In 2016, leaders from public safety, behavioral health and the Board of Supervisors announced a county-wide initiative, Diversion First, to offer incarceration alternatives for people with mental illness and/or developmental disabilities who are charged with minor offenses.

Diversion First Initiative

The Diversion First initiative is designed to divert people with mental illness, developmental disabilities and/or co-occurring substance use disorders from being jailed for low-level offenses. The initiative requires systems-level coordination between behavioral health treatment providers and criminal justice agencies to adequately understand, identify and meet the needs of these vulnerable county residents. More than 200 stakeholder groups are involved in the initiative, including representatives from the county’s executive board, law enforcement, courts, hospitals, fire and rescue, homelessness organizations, advocacy groups and elected officials.

In 2016, Fairfax County opened the Merrifield Crisis Response Center (MCRC), a location where law enforcement officers have the option to bring people needing behavioral health services rather than arresting them. The MCRC accepts walk-ins as well as law enforcement referrals, and all individuals who come to the center receive a mental health evaluation and a safe place to recover from a behavioral health crisis. Patients can also be connected to treatment providers and other services while at the center.

Following the opening of the MCRC, the county updated its Sequential Intercept Model (SIM) map as part of the Diversion First strategy. SIM is a conceptual framework used to inform community-based responses to people with mental illnesses and substance use disorders involved in the justice system. By focusing on where these individuals were encountering entities such as law enforcement, first responders, jails and courts, the county better understood service gaps and opportunities to support the right people and programs. SIM also offered an insightful way to assess what partners were and/or were not at the table to move this work forward.

The SIM map revealed an opportunity for Fairfax to expand Diversion First to include the development of a Co-Responder Model pilot. Noticing patterns of repeat 911 calls concurrent with repeat encounters with public safety, health and criminal justice systems, the county formed its Community Response Team (CRT) of case managers and law enforcement officers to respond to calls for police service involving a person experiencing a behavioral health crisis and connect them to the MCRC or other treatment providers. Co-responder programs have become a national best practice for communities serving individuals with mental illness, substance use disorders and developmental disabilities.

With a dedicated Data and Evaluation team, data plays a lead role in the Diversion First effort. Client and justice systems data are used to track progress, monitor outcomes, identify individual needs and coordinate care. Fairfax has been successful in establishing memorandums of understanding and data sharing agreements with partner agencies; however, these agreements have not led to a fully integrated data-sharing system. The county is seeking solutions to include health systems data and cost avoidance data, as well as develop ways to aggregate and safely store this information.

Boone County, Missouri

|

Target Population: People experiencing homelessness and frequent utilizers of the criminal justice system Vision: Decriminalize mental illness and homelessness Successes:

Challenges:

|

Boone County is a rural county located in central Missouri. Much of the population lives in the county seat of Columbia, Missouri's fourth largest city. In 2015, the Boone County Commission passed a resolution in support of the national Stepping Up initiative to reduce the number of people with mental illness in jails. This initiative formed the basis for other work in the community, including a focus on homelessness. The county established a collaborative working group, the Functional Zero Task Force (FZTF), which coordinates efforts across multiple organizations to reduce homelessness.

Integrated Data Framework and Matching Tool

Within Boone County, multiple systems capture information about their homeless and criminal justice populations including, but not limited to: FZTF By Name List, HMIS (Homeless Management Information System), VI-SPDAT (Vulnerability Index - Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool), JMS/RMS (Jail Records Management System/Records Management System), 911 calls and Emergency Department admissions.

Independently, these data repositories provide a snapshot of an individual’s situation rather than a comprehensive understanding of other influencing social factors. Recognizing the need for a more holistic view, the county sought to integrate systems-level data to better identify the urgent, complex needs of individuals with mental illnesses and/or substance use disorders. Doing so would promote the coordination of services, improve programs and prevent the high utilization of public systems.

Multiple partners supported this effort including the Boone County Commission, City of Columbia, law enforcement agencies, courts, Department of Public Health and Human Services, community development groups, housing authorities, Veterans’ Hospital and the University of Missouri.

In 2017, Boone County received a grant from the Corporation for Supportive Housing (CSH) to combat repeated imprisonment or jail time among the county's homeless residents. Since then, CSH, in collaboration with the University of Chicago, has developed a web-based data integration tool, which matches lists from county jail administrative data to local homelessness data. Merging these data sets allowed service providers to more accurately focus resources on the highest utilizers of those systems. For example, identifying chronically homeless individuals and providing housing interventions prevents them from entering or returning to the criminal justice system.

While the county has made significant progress through its partnership with CSH, it is looking beyond the criminal justice and homeless sectors to include social services and health care data. Integrating additional mental health treatment, hospital and dispatch data has the potential to reveal earlier intervention points, improve community conditions, produce cost savings across systems and reduce recidivism.

Merrimack County, New Hampshire

|

Target Population: Adults in the county's re-entry program Vision: Provide targeted services for people inside the jail to prevent them from cycling through the justice system Successes:

Challenges

|

Merrimack County is home to the state capital of Concord. With nearly 150,000 residents, Merrimack is New Hampshire’s third most populous county. In 2018, the Merrimack County Department of Corrections announced the opening of the Edna McKenna Community Corrections Center, which is home to the Successful Offender Adjustment and Re-entry Program (SOAR). SOAR relies heavily on community partnerships to deliver programming, counseling and case management.

Community-Based Partnerships and the Continuum of Care

Service providers from Riverbend Community Mental Health (RCH) work inside the Community Corrections Center (CCC) to provide intensive supervision, comprehensive case management and cognitive behavioral programming for people assigned to the SOAR program. With the goal of preparing people to make successful transitions back into the community, RCH provides one year of mandatory post-release aftercare while they are on probation. Because many clients in the program struggle with co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders, RCH ensures that trusting and supportive community-based relationships are in place prior to their release.

SOAR is a systems integrated approach to reducing recidivism in Merrimack County. Broad involvement in the project has led to having multiple champions from county offices and community organizations including law enforcement, courts, corrections, treatment providers and homeless organizations.

Even though all participating systems and agencies shared a similar goal, implementing SOAR introduced communication barriers among partners who struggled with cultural shifts and language differences. For example, clinical staff from RCH simply used different terminology than the corrections officers. However, with time, partners overcame these communication challenges, and champions eventually emerged when it became hard to tell the difference between an RCH staff member and a Community Corrections Center officer — the collaboration had become seamless.

The SOAR program upholds and supports the goal of Merrimack County’s Capital Area Public Health Network (PHN) to improve access to a comprehensive, coordinated continuum of behavioral health care services. The PHN is a network of 13 agencies from across the state that aligns multiple public health priorities into a single integrated system. In addition to using the same clinicians and mental health treatment providers for a year after the client’s release, RCH staff also develop resources, programming opportunities, and community-based relationships for safe integration back into the community. This approach positively affects people who have been incarcerated as well as the community by expanding the individuals’ support network. Through the provision of these services during incarceration and creating better integration within the community, people have a better chance of becoming productive members of their community.

Missoula County, Montana

|

Target Population: Families involved in dependent neglect cases Vision: Move upstream to prevent dependent neglect cases from happening Successes:

Challenges:

|

Missoula County is a geographically large, rural county located in western Montana. With a population of more than 100,000 residents, it is the second most populous county in the state. Since 2015, Missoula County has initiated several collaborative efforts to improve outcomes for people involved in the criminal justice system. In 2018, the county teamed up with Partnership Health Center (PHC) — Missoula County’s Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) — on the Kindness, Elegance, and Love Project (KELP). This project engaged new allies to serve justice-involved families dealing with parental termination proceedings.

Support Team for Dependent Neglect Cases

In 2017, the Montana State Office of Public Defender (OPD) contacted the Missoula County PHC about emerging non-criminal dependent neglect (DN) cases in the county. DN cases occur when a child is removed from the home and a 15-month plan is put in place for the parent by the court. After further investigation, the county and PHC learned that families involved in parental termination proceedings were not getting access to the evaluations or services needed to complete their court-ordered plan.

Also in 2017, the Montana State Legislature passed dramatic cuts to mental health and substance abuse treatment services. Missoula County’s public safety net, especially for those with mental illness and substance use disorders had weakened. Many of the families involved in DN cases were experiencing significant barriers such as mental illness and/or substance use disorders, developmental disabilities, generational poverty, poor health, unemployment, unstable housing and lack of transportation and/or childcare. As a result of the state-issued cuts, parents were losing their children due to their inability to access court-mandated services. After 15 months of being out of the home, it was presumed that it is in the best interest of the child to be permanently removed from the family.

Core stakeholders agreed that these families were not adequately being served. This led to cross-sector collaborations between the county, OPD, PHC, the University of Montana (UM) and several community service providers to enact change through the KELP program. Growing pains were anticipated because Missoula is a small, rural community where resources are limited and “turf wars” exist among agencies. Turf wars are an inherent risk when small communities compete with other departments and agencies for the same resources such as staff and funding.

A home site was designated for the KELP program near OPD and PHC. The location allowed for immediate intakes by licensed clinical social workers. Families now had access to mental health evaluations, housing assistance, guidance with court mandated plans (provided by UM Social Work and PhD Psychology students) and as many services possible to support the DN cases.

Adjacent to this effort of reunifying families, the county was also asking other pressing questions about the prevention and underlying causes of family removals, understanding the nuances that made Montana the number one removal state in the nation, and changing implicit biases and stigmas around these families.

For Missoula County, it’s been easy to get data-sharing agreements in place. However, data is used and stored very differently across agencies. Some are using electronic databases while others are still using paper files, making it impossible to integrate systems-level data. While it is unclear how Missoula County is measuring progress and success of its program, leaders acknowledge the need to mitigate turf wars to support collaborative systems integration.