A year later, 2020 hangs over county elections

Key Takeaways

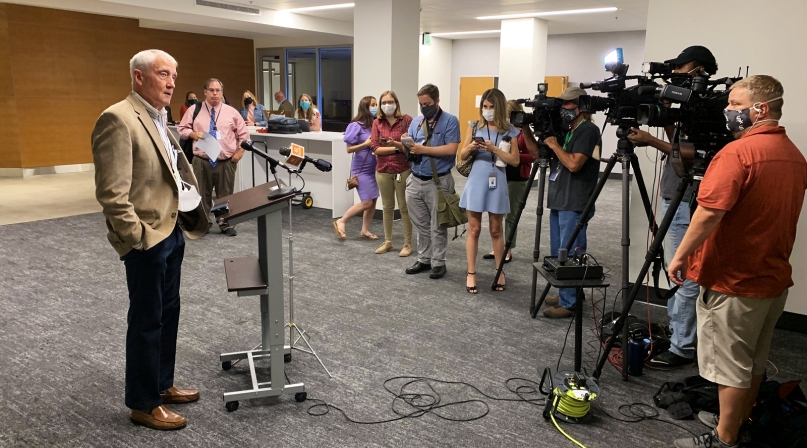

Every hour he spends dealing with the past is one Jack Sellers can’t spend working on the future. As the chairman of the Maricopa County, Ariz. Board of Supervisors, he has led the county’s pushback against criticism that prompted a lengthy audit that ended up confirming the results.

He’d rather focus on long-term infrastructure planning to ensure the county’s prosperity, years down the road, but he can’t ignore attacks on the foundation of representative democracy or his county’s reputation. So, he travels to Washington, D.C. to testify before the House Oversight and Reform Committee. He responds to the state Senate’s accusations. He engages with individuals who are certain something is rotten in Phoenix.

“I try to approach this all as noise — I have a job to do and that’s where my focus is, so I continue to attend all the same meetings, all the same functions, everything I always did,” Sellers said. “I’m just trying to keep things as normal as possible.”

But how much do those goals conflict?

“Not only has what’s gone on and on and on with the election challenges been frustrating, but I can’t help but keep thinking that the same people that we are in arguments with right now are the people I have to work with to accomplish what I need for infrastructure improvements and those types of things.”

Sellers also noted that most of the noise about the election’s integrity has come from political candidates angling ahead of their races, far outnumbering the feedback he has gotten from private citizens.

Some state Legislatures have been startled by the noise and are reacting reflexively, like in Iowa, where county auditors may no longer mail out absentee ballot request forms, deadlines are moved up and voting hours are shortened.

“Because of allegations of misconduct in other states, our Legislature passed laws that made it look like we were breaking laws willy-nilly,” said Grant Veeder, Black Hawk County, Iowa’s auditor.

A member of the Pennsylvania Senate was inspired by the Arizona audit and requested access to voting machines from three counties, all of which declined. Pennsylvania’s secretary of state ruled that allowing unauthorized access to voting machines will result in their decommissioning, with no reimbursement from the state to replace them. At the same time, the clerk and recorder in Mesa County, Colo. has done just that, after involvement with organizations disseminating election misinformation, and has been barred by a judge from overseeing November’s election.

“It’s a year after, but it still feels like the day after,” said Lisa Schaefer, executive director of the County Commissioners Association of Pennsylvania.

“Short of changing the results, I’m not sure what we can do to convince folks that we ran a good fair accurate election.”

Yavapai County, Ariz. Recorder Leslie Hoffman said the facts, such as the legal separation of responsibilities that prevents her from participating in parts of the elections process, often get little traction with the more passionate of her skeptics.

“They don’t want to accept the truth,” she said. “They don’t have any interest in knowing we saved $43,000 in return postage last year because people used drop boxes. And a lot of times, we get mail about the election from people who don’t even live in Yavapai County, so it’s not always our residents we’re getting feedback from.”

In Hoffman’s estimation, public health restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic affected people’s view of the election system.

“We lost the personal touch, where people would speak to an election worker in person,” she said. “They didn’t have someone help them vote in person, and we weren’t able to get out to schools, homeowners’ associations, Kiwanis Clubs and be part of the community. In a presidential election year, we’d be somewhere every day leading up to Election Day.”

Missouri county clerks have invited legislators to observe county elections operations, to see how they’re done, and the steps clerks take to verify security in hopes of proactively fending off laws that would limit their authority. Scotland County Clerk Batina Dodge said that initiative could help start a more informed conversation.

“We can help fill in the blanks for people, before they’re filled in by people who don’t work in elections,” she said.

Then there are the threats. Friends alerted Hoffman to some online postings about her. While it did not add up to actionable intelligence, the county sheriff has sent regular patrols past her house to check up on her safety.

Sellers has police protection too, though as a widower who lives alone, he is more concerned for county supervisors with families to protect. The sheriff told him to install a doorbell camera to add a layer of security to his house, particularly after answering the door following irate knocking by a stranger.

“I talked to him for 20 minutes and at the end, he said, ‘I still have unanswered questions, but at least I’m now convinced that you’re an honest, quality guy and I take back any bad thing I’ve ever said about you,” Sellers said. “My chief of staff said, ‘One down, 1.8 million to go.’”

Attachments

Jack Sellers, chairman of the Maricopa County, Ariz. Board of Supervisors, fields reporters’ questions. He has largely handled the county’s public response to unfounded allegations of improper administration of the 2020 election. Photo by Fields Moseley

Related News

MEGA Act moves in House; NACo raises county concerns

On Feb. 10, the U.S. House Committee on Administration held a hearing to consider the Make Elections Great Again (MEGA) Act (H.R. 7300), which was introduced by Committee Chairman Rep. Bryan Steil (R-Wis).

House passes SAVE Act; Major impacts on county election administration

Next week, the U.S. House of Representatives is slated to vote on the Safeguarding American Voter Eligibility (SAVE) Act (H.R. 22), making it the chamber’s second vote on a version of the legislation in less than a year.