Substance abuse hits home for county officials

Upcoming Events

Related News

Key Takeaways

For Doug Copenhaver, a parable has come to guide his view of the opioid crisis.

“There was an addict in a six-foot hole,” the story goes, “and a person walks by and says, ‘Hey, what are doing in that hole?’ And the guy says, ‘I’m an addict, and I don’t know my way out.’ The passerby says he’ll be right back.

A second guy comes along. Same conversation; same result. “The third person jumps in the hole and says, ‘I’ve been in the hole with you and I know the way out. Follow me,’” said Copenhaver, a Berkeley County, W.Va. councilman.

“The problem we had when we were fighting our son’s addiction was where do we go? We had no place to go,” he added. That changed with the opening of a Recovery Resource Center in his West Virginia Panhandle county (pop. 115,000) in 2016. “And now we have superb people in these positions that have been in trenches where these people are trying to dig themselves out.”

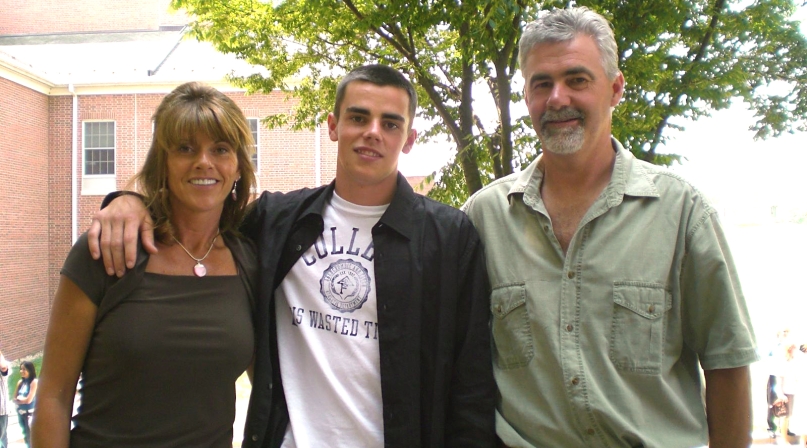

But 2016 was too late for the Copenhaver family. The councilman’s 22-year-old son, Douglas, crashed an SUV into a steel light pole at high speed after a traffic stop on Aug. 5, 2011.

He’d been in jail before for substance-use-related infractions and had told his father he didn’t want to go back. In earlier conversations, Douglas had suggested a third option to “getting clean” or going to jail. Copenhaver knew what he meant — his son had attempted suicide before.

“This affected him so bad that he chose the only way to get out of it was to take his own life. That’s very powerful control from the addiction on the opioid side,” the councilman said. Deaths like Douglas’ often don’t get counted among the statistics for opioid deaths but should be, some say.

Berkeley County saw 88 overdose deaths in 2016, but that number has been dropping over the past few years — to 54 in 2017, according to the West Virginia Health Statistics Center. While data from the state for 2018 has yet to be finalized, unofficial numbers show a continued decline. Local emergency-response agencies reported 33 opioid and heroin-related deaths in 2018, the coordinator of recovery services for the county, told the County Council recently.

As with all Americans, local elected officials are not immune to the ravages of the opioid crisis, but they have a bigger bully pulpit from which to share their stories.

More than 2,200 miles away as the crow flies from Copenhaver, in Skagit County, Wash., Commissioner Lisa Janicki also knows the pain of losing a child to opioid abuse. “I was looking at it at a policy level, a high academic level, and all of a sudden I’m submerged in the reality of a child in a rehab facility and then going through losing that son. It’s been a tough learning process.”

Since the death of her son Patrick, 30, in August 2107, the issue has become “more intensely personal” and she is “driven to talk to anybody and everybody,” Janicki said. Skagit County, population 124,000, had 298 nonfatal overdoses and 11 fatal overdoses in 2017, according to a December 2018 report from Skagit County Public Health.

Last September, the county hosted a Solutions to Addiction Symposium that drew an audience of about 500 to open a dialogue within the community. That includes “normalizing” the conversation around addiction — “you need that community support around the family, around the addict, around the person in recovery. If we don’t start having those community conversations, it’s just not going to happen,” Janicki said.

More recently, Skagit County commissioners passed an ordinance requiring medical professionals to report non-lethal opioid overdoses to the county public health department.

When it takes effect April 1, it will provide better data on the scope of the problem and make it easier to potentially get victims into treatment sooner after an overdose.

Janicki isn’t the only one of her county’s three commissioners to have been personally affected by the opioid crisis. Commissioner Ken Dahlstedt has a son who is still struggling with addiction with the help of a medically assisted treatment program.

His son, whom Dahlstedt declined to identify by name for privacy reasons, began taking prescribed opioid drugs after a back injury “six or seven” years ago. When the prescriptions ran out, “he ended up finding a less expensive alternative, which is heroin.”

Dahlstedt blames drug companies and distributors for minimizing the potential dangers of prescription opiates.

“A lot of the data shows they knowingly have continued to advertise, market and encourage the prescribing of these drugs, knowing that there’s a high level of addiction, and now, here we are with this crisis,” he said.

In January 2018, Skagit County and its cities of Mount Vernon, Sedro-Woolley and Burlington sued Purdue Pharma, Endo, Janssen, and other companies for the reckless promotion of opioids. That lawsuit has since been combined into a nationwide class action.

Skagit County is fortunate to be home to four Native American tribes that are also playing a key role in fighting the opioid crisis.

The Swinomish tribe built its own treatment center that specializes in addiction recovery services and has made those services available to the wider, non-native community.

Dahlstedt serves on a five-county consortium of behavioral health organizations. “We’re reaching out right now to the tribes in our five-county area to try to build a facility that will have beds available for detox and treatment for tribes as well as the citizens in general,” he said.

“I really see this as a partnership, bringing communities together because this opioid crisis is no respecter of persons or ethnicity. And so, we really see this as a maybe bonding opportunity for us to come together and fight a common enemy and that’s the opioid crisis.”

Attachments

Related News

Congress seeking ‘common-sense solutions’ to unmet mental health needs

Rep. Andrea Salinas (D-Ore.): “Right now, it is too difficult to access providers … and get mental health care in a facility that is the right size and also the appropriate acuity level to meet patients’ needs.”

Prince William County transforms crisis care through "No Wrong Door" approach

Prince William County, Va.’s Crisis Receiving Center is bridging the gap between emergency room care and traditional outpatient care in behavioral crisis response and reducing burden on local law enforcement and hospitals.

Federal-level child welfare priorities center on supporting foster youth, families

Child welfare experts outlined current priorities at the federal level, including better supporting foster care youth who age out of the system and recruiting more foster parents, at NACo’s Human Services and Education Policy Steering Committee meeting.