More fronts open in the war against opioids

Another county sues pharma over opioids while two settle, dangerous new blend hits the streets

Counties are continuing to grapple with the widening scope of the opioid drug epidemic.

Another county has filed suit against a pharmaceutical company that marketed painkillers, while King County continues to search for locations for its safe injection sites. Meanwhile, a synthetic drug is raising the stakes for users and first responders.

Orange County, N.Y. became the latest to take drug companies to task for misrepresenting the safety and efficacy of long-term use of opioid painkillers. Sitting on the New Jersey border, it’s the fourth New York county to pursue compensatory and punitive damages from drug companies, this time Purdue Pharma, Teva Pharmaceutical, Cephalon, Johnson & Johnson and Endo Health Solutions. Suffolk, Broome and Erie counties have also filed similar suits.

“As a county, we are working with nonprofits and physicians to bring heightened awareness to the issue, “ County Executive Steven Neuhaus said when announcing the suit May 11. “At the same time, we want those responsible to compensate for the public funds the county has had to pay to address opioid addiction.”

In 2015, 44 Orange County residents died from opioid overdoses, and the 943 opioid-related hospital admissions in 2014 was a 17.5 percent increase over 2010.

Outside of New York, three counties in West Virginia and one in Illinois have pursued action against drug companies. California’s Santa Clara and Orange counties announced a settlement May 24 in a lawsuit against Cephalon and Teva over alleged deceptive marketing practices for their opioid painkillers. The settlement will provide $1.6 million for substance abuse treatment and education in the two counties.

A place to go

In February, King County, Wash. moved ahead to establish two Community Health Engagement Locations (CHEL), where addicts could take their drugs under supervision of medical staff, exchange used needles for sterile ones and access addiction recovery programming.

One CHEL was planned for Seattle and one for the rest of the county, but so far, site selection has held up the process.

“We’re being pretty open-minded about where we place the first one,” said King County Health Officer Jeff Duchin. “We’d love to open two simultaneously, but finding suitable sites makes that unlikely.”

Duchin is a member of the King County Heroin and Opioid Task Force, which recently had several recommendations to lower barriers to opioid addiction treatment and health service operation included in a bill signed by Gov. Jay Inslee.

Although there has been some pushback, including from a state senator who represents part of King County and sponsored a bill in his chamber outlawing the CHELs, Duchin said the biggest impediment has been the process of finding the best location.

“We’re looking for a place with a lot of need for what we offer,” he said. “Somewhere where there is a concentrated population of users who are injecting in public and could benefit from the linkages to health services we could offer.”

The county is looking for the greatest impact location, where it could reach as many addicts as possible.

“It would be premature to engage with any community at this point since we’re so far away from finalizing a site,” Duchin said.

But that could change quickly, he said, once they identify a site.

Gray Death

In January, police intelligence reports told the Warren County, Ohio Sheriff ’s Office that there was a new opioid drug on the market, a combination of three potent varieties

that could be deadly in small amounts.

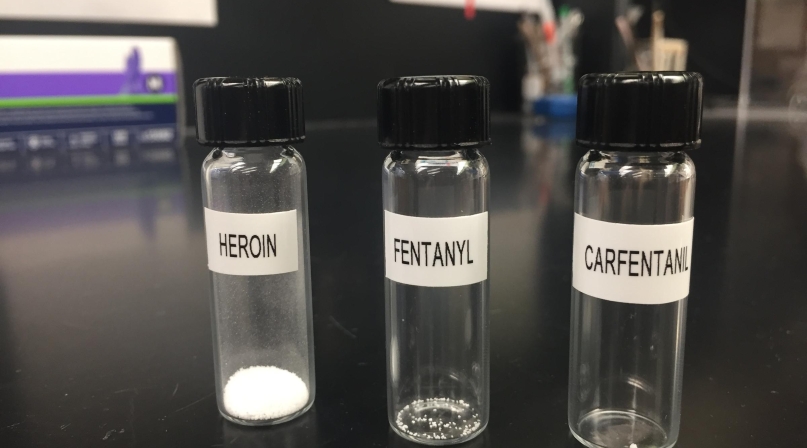

In mid-May, the county northeast of Cincinnati was confirmed to be a home of “Gray Death,” named for its resemblance to cement. It’s a combination of heroin, fentanyl and carfentanil, each more potent than the last, and it has been detected in overdose deaths in Ohio, Georgia, Florida and Alabama.

“This is very new,” said Warren County Chief Deputy Barry Reilly. “It’s even more of a threat because it’s so potent, and it can be absorbed through the skin or inhaled, so it’s a hazard to a first responder answering a call or someone who finds a family member who has overdosed on it. They touch them and get it on their skin or inhale it if they kick it up into the air.”

Still, despite the danger, Reilly said the Warren County Sheriff ’s Office has no plans to change its standard procedures out of fear.

“We’re not going to not stop cars and we’re not going to not make arrests,” he said. “If it’s a situation where we can plan ahead and wear gloves and respirators, we’ll do that. Otherwise, everyone is equipped with naloxone, so if someone is having trouble, we administer that.”

Clay Hammac, drug task force commander for the Shelby County, Ala. Sheriff ’s Office, said education was crucial to turning people away from increasingly potent drug cocktails.

“This isn’t going to give you a casual relaxing high,” he said. “If you ingest Gray Death, it will kill you. Regardless of how matter of fact we are about this, folks are flocking to it.”

Fentanyl’s lethal dose is the size of two grains of table salt, while carfentanil’s dose is the size of one grain of salt.

“We have to make the public aware that these are street level dealers, not pharmacists. They’re not interested in the health and safety of the public, they’re mixing this stuff up in their kitchen sinks.”

Attachments

Related News

National Association of Counties Launches Initiative to Strengthen County Human Services Systems

The National Association of Counties (NACo) announces the launch of the Transforming Human Services Initiative, a new effort to help counties modernize benefits administration, integrate service delivery systems and strengthen county capacity to fulfill our responsibility as America’s safety net for children and families.

Congress seeking ‘common-sense solutions’ to unmet mental health needs

Rep. Andrea Salinas (D-Ore.): “Right now, it is too difficult to access providers … and get mental health care in a facility that is the right size and also the appropriate acuity level to meet patients’ needs.”

Prince William County transforms crisis care through "No Wrong Door" approach

Prince William County, Va.’s Crisis Receiving Center is bridging the gap between emergency room care and traditional outpatient care in behavioral crisis response and reducing burden on local law enforcement and hospitals.