What the suburbanization of poverty means for U.S. counties

Author

Upcoming Events

Related News

Fragmentation in suburban areas, program delivery adds challenges for poverty issues

The recent election cycle and the parsing of its largely unpredicted outcome helped bring attention to the economic struggles facing a wide swath of communities across the country — from President Trump’s repeated invocations of the disastrous plight of “inner cities” to the post-election commentaries on the role of economically distressed rural communities in electing Trump to the presidency.

As of 2015, 43.1 million people — or 13.5 percent of the country — lived below the federal poverty line. While that number marks an improvement over 2014, it is still 5.8 million more compared to 2007’s pre-recession count and 11.5 million more than in 2000. The election-cycle narrative captured the economic anxiety many Americans continue to feel several years into an economic recovery that has yet to bring poverty back to pre-recession levels.

But it largely missed the fact that the communities bearing the brunt of growing poverty over the 2000s were not just urban or rural. The nation’s suburbs accounted for roughly half (48 percent) of the uptick in the poor population between 2000 and 2015, making suburbia home to the not only the fastest-growing poor population in the country but also the largest. By 2015, the suburban poor population outnumbered the poor in big cities by more than 3 million and the rural poor population by more than 8 million people.

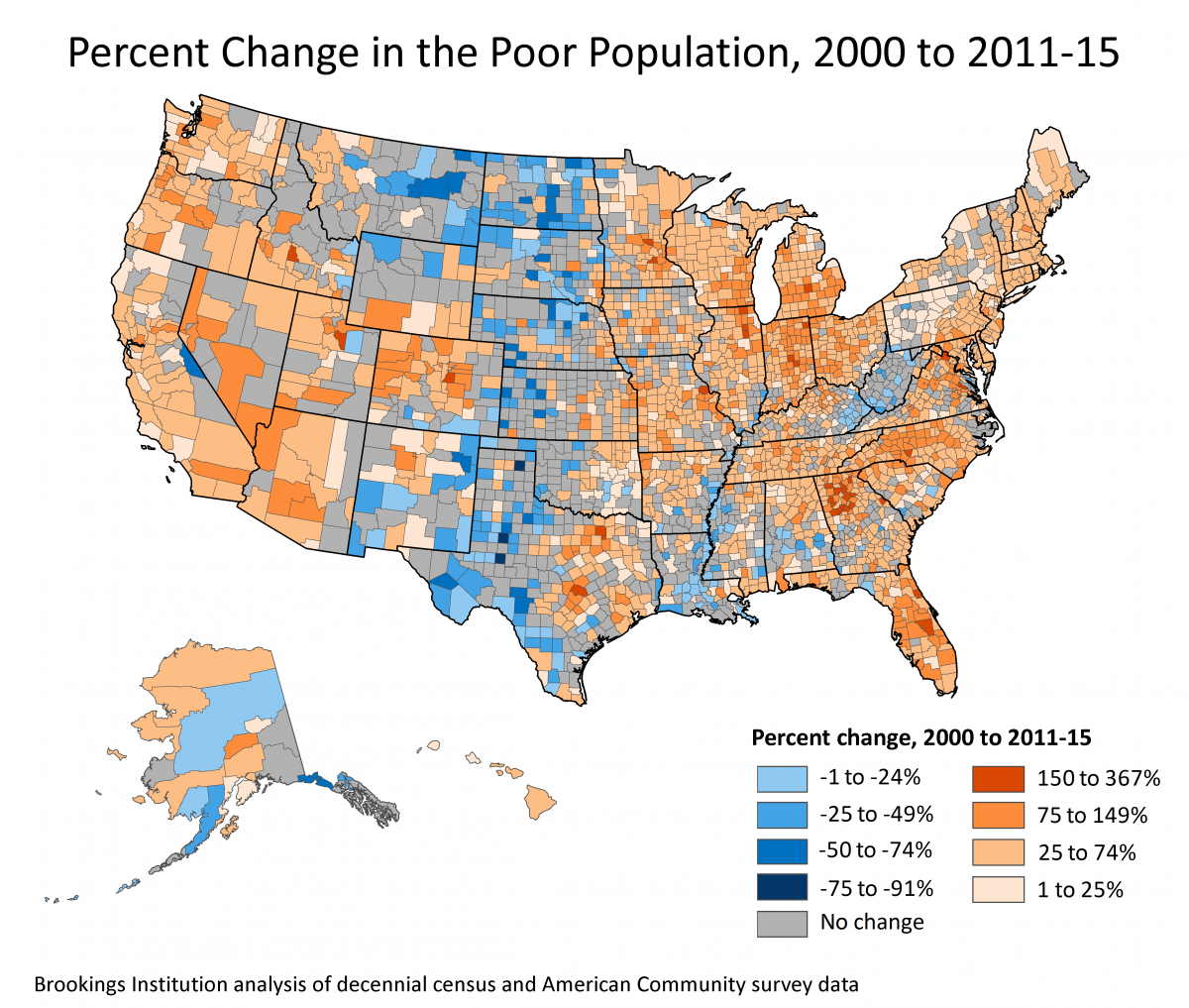

That is not to say that urban and rural communities did not experience rising poverty. The majority of the nation’s counties — 62 percent — registered significant increases in poverty in the 2000s (see map). Sorting counties into different categories — urban, suburban, small metro and rural — makes it clear that growing poverty was a challenge felt across the geographic spectrum (see chart, page 17).

Some definitions

Urban counties are counties in the 100 largest metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) that contain a primary city (population of 100,000 or more), or at least half the population of a primary city, and have an urbanization rate of 95 percent or more.

Suburban counties are all other counties in the 100 largest metro areas and are further categorized by their urbanization rates as follows: High Density (95 percent or more), Mature (between 75 and 95 percent), Emerging (between 25 and 75 percent), and Exurban (less than 25 percent).

Small Metro counties fall in an MSA outside the top 100

Rural counties are those that are not part of an MSA.

Yet taken together, suburban counties experienced by far the steepest uptick in the poor population between 2000 and 2015, with an increase of 64 percent. While older, more urbanized suburbs saw some of the sharpest increases, growing poverty also reached beyond “inner-ring” suburbs to lower-density and exurban counties.

As much as feelings of economic anxiety may have contributed to Trump’s win, poverty’s growth over the 2000s cut across party lines. On one hand, the pace of growth in the poor population tended to be faster in counties won by Trump. But the 489 counties won by Hillary Clinton were home to most of the nation’s poor population (56 percent). Those counties also tended to have somewhat higher poverty rates on average compared to the 2,613 counties that Trump carried. The exception was in suburban counties, which posted slightly higher poverty rates in areas that went for Trump.

These numbers underscore the fact the 2000s saw the challenges of poverty become more widely shared as communities across the country were buffeted by a combination of forces that not only drove poverty up but also expanded its geographic reach.

The last decade was bookended by two economic downturns that played a significant role in the rapid rise of poverty in the 2000s, as did longer-running structural economic changes, like the growth of low-wage work and erosion of middle-class jobs. But the changing geography of poverty has also been shaped by other factors, including the continued shift of jobs away from downtowns, regional housing market trends and the changing location of affordable housing, and shifting immigration patterns.

While suburbs are a diverse mix of places, much more so than popular stereotypes would suggest, many face common challenges when it comes to addressing the recent rapid growth of poverty. The suburban safety net tends to be less extensive and spread thinner than in cities, and resources often haven’t kept up with the pace of growing need. Public transit is often limited or simply not available, which can make it that much harder for residents to access services or to overcome the growing distance between where they live and where jobs are located. And the fragmented nature of both suburban jurisdictions and anti-poverty programs can complicate efforts to address shared challenges effectively.

Even in the face of these challenges, local and regional leaders are finding innovative ways to respond to the broader reach of poverty by crafting more scaled and collaborative solutions. Many counties across the country have taken leadership roles in these efforts, taking advantage of the scale at which they operate to help overcome the challenges outlined above.

For example, in 2009 Montgomery County, Md., worked with local services providers, funders, and the community to create the Neighborhood Opportunity Network — a more streamlined and culturally competent service-delivery model built to respond more effectively to increasing poverty and rapid demographic change in the county.

In 2015, King County, Wash., rolled out ORCA Lift, a reduced-fare program to help make transit more affordable for low-income residents, the majority of whom live in Seattle’s suburbs.

Not only do these examples show the important role counties can play in better connecting residents to opportunity, innovative local and regional efforts like these can help inform an anti-poverty policy agenda at all levels of government that more effectively addresses the scale and reach of today’s geography of poverty.

Attachments

Related News

Inland port offers opportunity for Hertford County, N.C.

Hertford County, N.C. doesn’t have a lighthouse, but that hasn’t stopped its economic future from shining thanks to what became known as Project Green Lantern.

Chamber of commerce program helps keep workers on the job

Audrain County, Mo.'s Workforce Resource Assistance Program has helped employers keep staff in place, reducing turnover and promoting stability.

County leadership guides shared prosperity

There’s no chicken-or-egg debate: Economic mobility is not just a byproduct of growth — it is the result of intentional county governance.