Adult homeless strategies, poor fit for youths

What works for homeless adults may not always be developmentally-appropriate for under age 24

After an uncertain stretch on the streets, a young person makes it into a shelter, then finds himself rapidly re-housed — placed in an apartment by himself. And that’s not always good news.

That’s the wrong way to approach youth homelessness, according to organizations that provide youth services to counties, and it illustrates the disconnect between public policy and the situations young people are facing when they don’t have homes.

“The needs of homeless youth are vastly different from homeless adults,” said Paul Hamann, president and CEO of the Night Ministry, a Cook County, Ill. service provider. “There needs to be a continuum of options available, because if you rapidly re-house a young person in an apartment by themselves, especially if they’ve never lived by themselves, it usually doesn’t do too well for them.”

Melinda Giovengo, president and CEO of YouthCare, King County, Wash.’s youth homeless service provider, agrees.

“Housing is an integral part, but for young people, you were only putting a bandage on situations. If you’re not connecting young people on a true path to exit homelessness, they’re going to fail. They probably haven’t lived by themselves and supported themselves (like adults placed in rapid re-housing), so when their rent subsidy runs out, they’ll probably be evicted.”

This confluence makes sense to David Pirtle, public educational coordinator for the National Coalition for the Homeless.

“They’re the last people we think of when we think of homeless folks,” he said. “They’re an afterthought when it comes to programming, and they’re harder to count because they don’t come use services the way adults do. They don’t always know where to go.”

The 2014 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development point-in-time count pegged youths under 24 as 34 percent of the national homeless population.

Giovengo suggests transitional housing, which is more temporary and more service-delivery intensive, but meets the needs of a developing person. But, HUD does not fund transitional housing as it once did, which makes it difficult to afford.

Hamann would like a developmentally appropriate compromise that places several youths in a group living situation with structured programming and supervision.

Giovengo said job training and education has to be a part of the path out of homelessness.

“Biggest question we’re asked is ‘Can you help me get a job?” she said.

With all concerns about housing in mind, the most important function is just getting kids into some kind of shelter.

“The most vulnerable moment is the child’s first night on the street,” Giovengo said. “In the first 48 hours, you will be raped, robbed or beaten. It doesn’t take long for homelessness to take a toll on young people. We have to do everything we can to prevent a young person from spending a night on the street.”

Just as the route out of homelessness is different for adults and youths, who are broken down to the 13–17 and 18–24 age groups, the paths that brought them there are different, too.

Where lost jobs or mental health or substance abuse disorders are typically the largest contributors to adult homelessness, youths age out of foster care or juvenile justice systems or run away from or are kicked out of their homes.

National estimates put the population of LGBTQ homeless youth at 40 percent of the total homeless youth population. In Harris County, Texas, 48 percent of homeless LGBTQ youth reported being kicked out of their family homes.

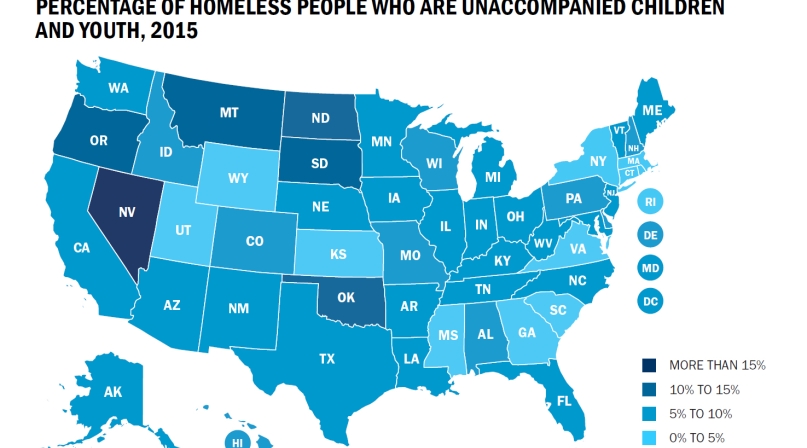

Homeless youths of all kinds gravitate to urban areas, with the population, culture and community most likely to support them, yet counties remain the bedrock social safety net and provide services regardless of jurisdictional lines.

Giovengo said that King County youth typically gravitate toward the urban centers — there’s a large encampment beneath Interstate 5 — and stick to their age range.

“Adult homeless camps are pretty frightening for kids,” she said.

Though her organization does outreach to many of the camps, bringing food and clean water, drug dealers and pimps also prey upon the kids there.

“They’ll give them a free sample (of drugs) to get them hooked,” she said. “A lot of the kids are looking for something to anesthetize them to what’s happening.”

Roughly 70 percent of homeless youth report having engaged in “survival sex” to secure housing, food or money, and the most effective response King and many other counties have found is to not prosecute prostitution, but rather target the traffickers.

“If you’re a 13- or 14-year-old, alone for 45 minutes at the Westlake Mall, a pimp or John will approach you,” she said.

As for where to go, Giovengo said a good start is getting a count of the youth homeless population, from which to base programming. King County’s Count Us In report found 824 homeless and unstably housed youths on Jan. 28, 2016.

“Every year we’re within about 100 of the last year, always between 700 and 1,000,” she said. “The number gave us a target, but it’s also a number the community and the funders can plan around you can plan solvable solutions for.”

Hamann said counties can improve their youth homeless services by coordinating where departments that interact with them, then share data, which can go a long way to getting a better picture of the homeless youth they’re dealing with.

He also suggests counties pay for transitional housing that will better serve the youths’ developmental needs.

“There is definitely a role for the county to play in funding alternative housing options,” he said.

Prevention programs help.

“If there was a place for kids to cool off when there’s tension with their family, that would help stop a lot of rash decisions,” Hamann said. “If we could get a good preventive system in place, we can probably cut the population by one-third.”

Giovengo set King County’s goal as one of an outfielder diving to make a catch.

“We can’t prevent every child from leaving home or every family from breaking up, but we can prevent every child from sleeping in the street,” she said. "We have to do everything we can to prevent a young person from spending a night on the street. The longer a young person is out there, the harder it is to get them back inside".

And that first night is an eye-opener.

Pirtle, who was himself homeless for two-and-a-half years as an adult, found some common ground with homeless youths he met during that time.

“The most terrifying thing is realizing everything you don’t know that first night,” he said.

Attachments

Related News

County Countdown – Nov. 17, 2025

Every other week, NACo's County Countdown reviews top federal policy advocacy items with an eye towards counties and the intergovernmental partnership.