Advancing Local Housing Affordability: NACo Housing Task Force Final Report

Upcoming Events

Related News

The Need for Access to Moderately-Priced, Fair-Quality Housing in All Counties

For a growing number of Americans, the cost of housing is crowding out the rest of their household budget. That’s forcing many families into precarious living situations that affect their safety, their health, the length of their commutes and their chance to build generational wealth or to contribute to a vibrant community where they feel like they have a stake.

In 18 percent of counties, households spend more than 3.5 times their annual income to afford a typical home. Nearly a quarter (23 percent) of households that occupy rental units are severely cost-burdened, spending more than half of their annual income on rent. There is a shortage of more than 3.8 million homes across the country, according to Freddie Mac, and it will take more than 20 years to close the housing unit gap despite the recent acceleration in development, according to the National Association of Realtors.

These statistics lend context to a problem counties know all too well: housing affordability is increasingly out of reach for residents. In Valley County, Idaho, a small resort community outside of Boise, the median home price is $650,000, while the median household income is only $75,000 – primarily driven by the influx of wealthy households. First responders, service- sector and healthcare workers, teachers and other community members face the choice of commuting several hours or living in homes not intended for long-term habitation like Recreational Vehicles (RVs). For children from the community, there is virtually no path that leads to living in the county where they’ve grown up.

Across the country in Franklin County, Ohio, the bustling home to the capital city of Columbus, four out of every ten renters are cost-burdened, spending more than 30 percent of their annual income on housing. The lingering impacts of decades of unjust housing policies like redlining, access to financial institutions and affordable financing still cloud the pathways to homeownership for many black and brown residents.

Stories like these are not the exception but a commonality across many counties in this country. Housing fulfills the basic human need for shelter and is the foundation for better health, consistent education, a stronger workforce, improved financial wellness, and lowered demand for the public sector safety net.

Housing experts, policymakers and data illuminate three persistent barriers for access to housing: affordability, supply and quality. In November 2022, NACo President Denise Winfrey launched a national task force of county officials to study housing affordability, charged with two goals: identify county-led policy, practice and partnership solutions to addressing America’s housing affordability crisis, and explore intergovernmental partnership opportunities that support housing solutions between federal, state and local officials, along with private, nonprofit and other community organizations.

Housing policy is a highly complex, multi-layered topic requiring bipartisan partnerships, dialogue and coordination across all levels of government, private and nonprofit organizations and the community. It is not a partisan issue but one impacting residents of all political, demographic, geographic and socioeconomic stripes.

Since late 2022, the task force met with experts and policymakers, studied data and trends, and analyzed county authorities and strategies to foster housing affordability. While there is no simple solution to housing affordability, counties can work within our policy, financial, convening, educational and administrative levers to be a part of the effort to generate and preserve housing so our neighbors, communities and the next generation can have a better future.

“Counties are on the front lines of responding to the housing crisis. Stable, quality housing is the foundation for better health, safety, education, a strong workforce, improved financial wellness, and lower demands on the social safety net. [Counties are] committed to meeting the moment and addressing our residents’ housing needs.”

2022-2023 NACo President Denise Winfrey

Will County, Ill. Commissioner

The Perfect Storm for a Housing Affordability Crisis

Many colliding factors contribute to the current housing affordability crisis.

Housing costs have been steadily rising, often outpacing inflation or wage growth. Roughly half (46 percent) of renters and over one in three homeowners (35.1 percent) were cost-burdened in 2021, including 23 percent of renters and 9 percent of homeowners who spent at least half of their household income on housing throughout the year.¹ Compounding these burdens, the median price of a home surged by more than $107,000 between Q1 2020 and Q1 2023.² Furthermore, rents have increased by 16 percent between January 2020 and March 2023, with additional rent increases expected in the coming months.³ With wages increases struggling to keep pace for many in the workforce over the last several decades, the increase in the costs of housing are straining renters and homeowners alike.

Not only are Americans facing higher housing costs, but the stock available for renting or owning is also increasingly limited and, too often, in disrepair. The number of active housing listings in June 2023 was at one of the lowest levels since 2016 and 34 percent lower than the number of listings in February 2020.⁴ Moreover, the number of available rental units has been cut nearly in half over the past decade (10 percent in 2010 vs. 5.2 percent at the end of 2021 vacancy rates).⁵

For the available homes, the Philadelphia Federal Reserve concluded roughly one-third had significant non-cosmetic deficiencies in 2022, conveying an estimated price tag of $149.3 billion for repairs.⁶ Increased repair costs are, in part, a byproduct of older housing stock. The Median age of homes increased to 43 years old in 2021.⁷ Plus, soaring construction costs (materials and labor) during the pandemic exacerbated the challenge.⁸

As the population demographics continue to shift, approximately 40 percent of housing stock lacks accessibility like an entry-level bedroom and bathroom necessary to serve older generations and those with reduced mobility issues.⁹ Moreover, the increasing frequency of natural disasters significantly threatens the existing housing stock. Throughout 2022, there were 18 unique billion-dollar natural disasters; when combined with the past seven years, the total price tag exceeds $1 trillion, constituting more than one-third of the entire disaster cost over the past 42 years.¹⁰

Though housing has been a critical discussion point in the body politic for decades, the problem has grown in scope. During the pandemic, a sample of landlords reporting collection rates above 90 percent fell from 89 percent in 2019 to 62 percent in 2020.¹¹ Those experiencing particular hardship during the pandemic tended to be low-income or of Hispanic origin.¹² Additionally, as flexible work options become more mainstream anecdotes of individuals seeking a different environment to work from – in a lower cost- of-living area – have skyrocketed and, in some cases, are pricing locals out of their home communities.¹³

Housing Affordability Is a Complex Issue Requiring Strong Partnerships, Dialogue and Coordination

Counties face significant headwinds when it comes to housing affordability. Across federal, state, local, private and community sectors, authority and responsibility to impact housing affordability varies. All of these intersections weave a complex system to navigate. As such, it is critical for counties to engage in dialogue and coordination to build strong relationships with the stakeholders impacting housing. Below is a sample of the continuum of factors impacting housing supply and affordability.

Global and National

- Housing materials supply chains

- Housing investments and programs

- Monetary policy and interest rates

- Tax policy and housing laws

- Labor laws

State Governments

- Tax policies and incentives

- Disaster mitigation

- Building codes & local housing law preemption

- Land use and zoning framework

Sub-State Regional and Local Governments

- Tax policies and incentives – particularly county property taxes

- Local building codes, ordinances and land use

- Programs, investments and services in housing, workforce, infrastructure and transportation

- Disaster and emergency preparedness and mitigation

Private Markets

- Global and national investors, lenders and insurers

- Technology disrupters such as shared service providers

- Housing developers and financial institutions

- Rental markets and landlord practices

- Skilled labor shortages and wages

Community Members and Public Interests

- Historically designated areas

- Community land use interests

- Nonprofit and community-based organizations delivering housing services

- Neighborhood associations, community groups and local advocates

“Government is not the solution for local housing issues but needs to be a part of the conversations surrounding how we can and should find common goals and solutions for a growing problem.”

NACo Housing Task Force Co-Chair Sherry Maupin

Valley County, Idaho, Commissioner

The County Housing Ecosystem

Housing spans a wide range of touchpoints in many counties. Though county authorities vary, each county can play a role in the solution. There are five key areas in which counties may possess the authority to foster housing affordability.

County Housing Touchpoints

Community Engagement, Partnerships and Education

Much of the work required to increase housing stock depends on engagement with the community. Not only can counties partner with other governments, private sector officials and community organizations to advance housing, but local leaders can also serve as an educational body to inform residents.

Federal-County Intergovernmental Nexus

Federal funding – such as the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) – is often used by counties to administer housing programs, build infrastructure that supports new development and provide assistance for low-income residents.

Finance, Lending and County Tax Policy

Property taxes are the primary driver of most county finances and can play a significant role in the use of land. Additionally, some counties work with financial institutions or leverage federal programs to provide direct support to individuals or incentives for new developments, homeownership and other housing programs.

Land Use, Zoning, Infrastructure and Community Planning

Zoning is important to designate how a parcel of land is used within a community, and a community land use plan seeks to properly map out the land within a county jurisdiction. Further, to build housing requires infrastructure like roads, utilities and broadband, some of which counties build, maintain, regulate or otherwise support.

Regulation, Codes and Associated Feeds

Developing a property for housing requires following a set of codes and regulations to ensure safety. Counties often issue permits and conduct code enforcement, and some developments require studies or carry other special fees associated with construction.

NACo Housing Task Force:

Abbreviated Best Practices and Policy Recommendations

Check out the NACo Housing Task Force's county solutions for housing affordability

Housing affordability is complex, multifaceted and interdependent. So too are county authorities and resources on local housing policy, financing and regulation. Because of the varied authorities, each county’s approach to addressing the challenge is different. Recognizing the acute need for housing affordability, the county housing ecosystem and associated recommendations seek to provide local leaders an opportunity for best practices and policy that reflects the diverse tools of county governments.

It is also important to recognize that each policy or ecosystem pillar does not exist independently, but are pieces of a whole. The land use and zoning plans in a community ultimately impact the county tax base and services; the partnerships established within a community can inform state and federal advocacyefforts; use of federal funds can reflect financing of new developments; and local regulations can have significant implications on community engagement. Recognizing this interconnection is important to understanding the levers and opportunities available to counties to foster affordability and quality.

Regardless of the county approach, the process of creating solutions for housing affordability at the local level is often slow, contentious and grueling. This recommendation framework does not intend to provide a prescriptive implementation guide. Rather, this document provides a broad set of tools and examples county leaders may use to develop a local housing action plan that reflects each community's unique needs, values and priorities and considers the varied relationships and resources available.

1. Land Use, Zoning, Infrastructure And Community Planning

a. Evaluate Current Zoning Plans and Practices

b. Identify Potential Infrastructure Barriers to New Development

c. Understand the Inventory of Additional Land

d. Develop a Long-Term Housing and Land Use Plan

e. Assess Existing Housing Stock for Potential Opportunities

2. Local Regulation, Permitting And Fees

a. Evaluate County Permitting and Inspections to Improve Processes and Workflow

b. Provide Pre-Approved Templates for

Common Housing Designs

c. Conduct a Cost- Benefit Analysis for County Impact, Development, and General Fee Pricing

d. Analyze Local Regulations Impact on Affordability

e. Make County Systems Consistent, Convenient, and Easier to Navigate

3. Federal-County Intergovernmental Nexus

a. Invest Additional Federal Resources to Support Housing

b. Engage in NACo Policy Resolution Process to Advocate for Counties

c. Educate Federal and State Partners on Local Housing Needs and Simplify Programs and Compliance

d. Seek Additional Funding Opportunities as Resources Allow

e. Combine Resources for Maximum Impact

4. Community Engagement, Partnerships and Education

a. Collaborate with Intergovernmental Partners

b. Establish an Office or Department to Streamline Housing Projects

c. Foster a Healthy Dialogue with Community Organizations

d. Conduct a Robust Outreach and Education Initiative

e. Measure Success and Clearly Communicate Milestones

5. Finance, Lending and County Tax Policy

a. Identify Opportunities for Tax Incentives or Policy Updates

b. Analyze the County Assessment Process

c. Administer Supportive Programs That Prioritize Underserved Communities

d. Partner with Local Organizations to Provide Innovative Financing Mechanisms for New Development

e. Source New Revenue Streams for County Housing Priorities

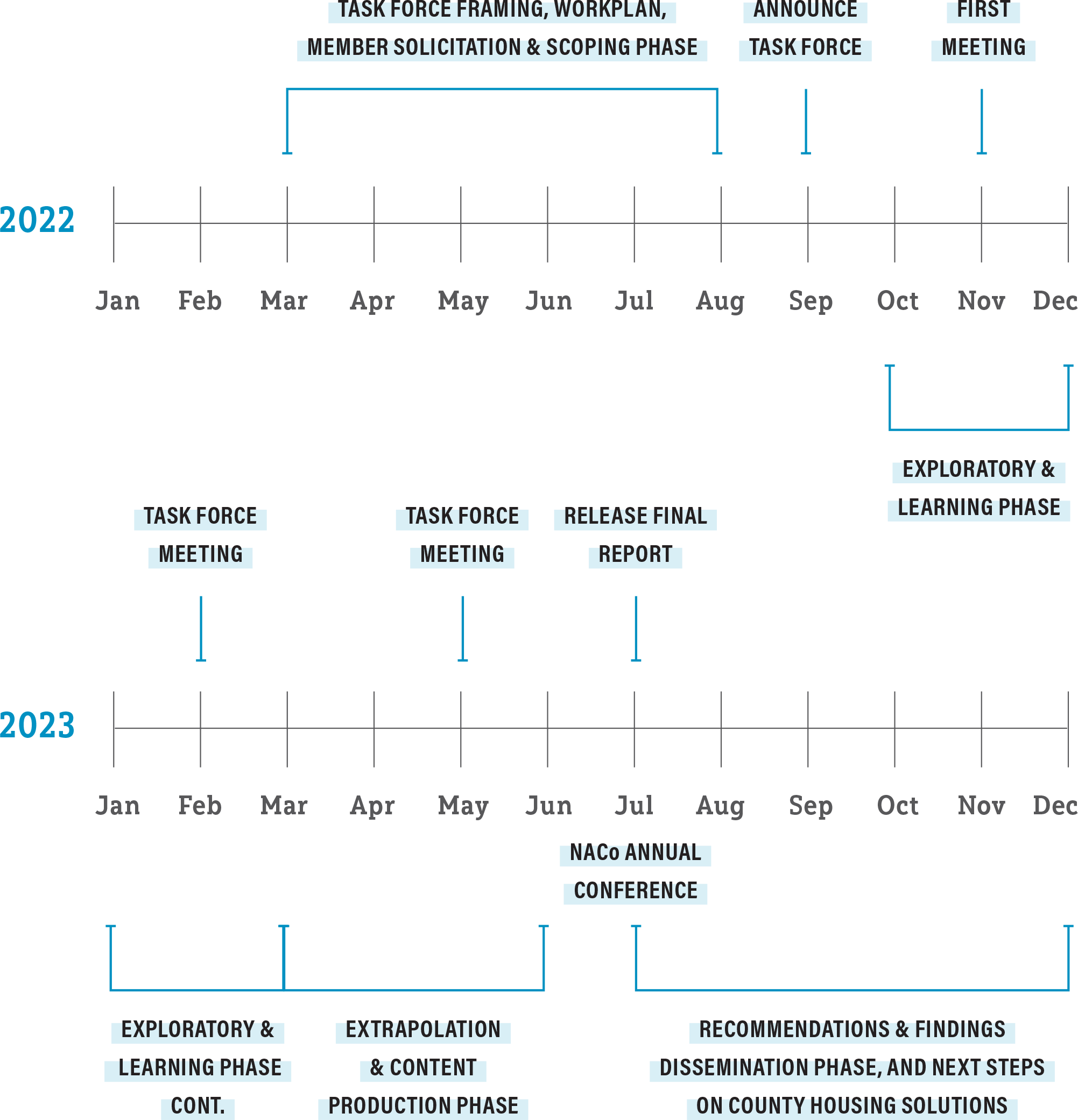

NACo Housing Task Force Process

In November 2022, NACo President Denise Winfrey launched the Housing Task Force, a group of 33 elected and professional county housing experts. President Winfrey charged the task force with two goals: to elevate county-led solutions to address the housing affordability crisis confronting America’s counties and identify intergovernmental opportunities for partnership on housing issues.

The task force work began in earnest in November 2022, with an in-person convening to explore the county's role in housing. Led by co-chairs Sherry Maupin and Kevin Boyce, Commissioners from Valley County, Idaho and Franklin County, Ohio, respectively, task force members engaged in discussion with experts from the Harvard Joint Center for Housing, the

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the Aspen Institute – the task force partner – on county authority, challenges and solutions to housing affordability.

Five core focus areas emerged from these conversations to form the County Housing Ecosystem.

- The federal-county intergovernmental nexus

- Local regulations, codes and fees

- Finance, lending and county tax policy

- Land use, zoning, infrastructure and community planning

- Community engagement, partnerships and education

Meeting again in February 2023 during the NACo Legislative Conference in Washington, D.C., the task force explored these areas with in-depth conversations on homeownership, rental housing and technology solutions. The task force also participated

in an open discussion with White House senior leadership on the federal-to-county nexus and areas for intergovernmental collaboration.

Over the following months, the task force met virtually with experts from around the country to discuss the financial, administrative and policy levers counties can employ to affect change. During the final in-person meeting in May 2023 in Dallas County, Texas, task force members explored some of these solutions in action.

From the task force work, a recommendation guide for local leaders seeking to advance housing affordability has been born. The framework is not a silver bullet solution, and housing affordability does not come to fruition overnight. However, the framework provides a guide – a point of origin – for leaders seeking change, wherever they may be starting the housing affordability journey. Though county authority on housing is complex and varied, the task force guide aims to be another tool in the county toolbox from which local leaders can draw ideas, inspiration, projects and solutions that can be tailored to fit the unique needs of each community.

Though the work of counties on advancing housing affordability is not done, the release of the recommendation framework marks a milestone in the county effort to build strong communities and ensure equitable access to safe, quality and reasonably priced housing for every resident in every county across the country.

NACo Housing Task Force Timeline

“Our nation is facing a perfect storm of factors that contribute to the housing crisis. We are focused on addressing challenges and expanding opportunities for our residents to achieve the American dream of housing security.”

NACo Housing Task Force Co-Chair Kevin Boyce

Franklin County, Ohio, Commissioner

Appendix A: Acknowledgements

Recommendations in the Advancing Local Housing Affordability document were developed by members of NACo’s task force on housing affordability; recommendations may not necessarily reflect individual task force members’ views. NACo thanks the task force members – particularly co-chairs Commissioner Kevin Boyce of Franklin County and Commissioner Sherry Maupin of Valley County – for their tireless dedication to advocating for local solutions to housing affordability.

NACo’s task force on housing affordability was generously funded in part by the Aspen Institute Financial Security Program (Aspen FSP). Any findings, recommendations or anecdotes reflected in the report do not necessarily reflect the views of Aspen FSP.

This report was compiled by Kevin Shrawder, NACo’s Senior Analyst for Economics and Government Studies, with support from Jesse Priddy, NACo’s Housing Policy Fellow. They would like to thank NACo colleagues including Mike Matthews, Legislative Director for Community, Economic and Workforce Development; Julia Cortina, Legislative Associate; Jonathan Harris, Associate Director, Research; Ricardo Aguilar, Associate Director, Data Analytics; and Stacy Nakintu, Sr. Analyst for Research and Data Analytics for their contributions to the task force work.

Appendix B: Task Force Members

Launched in November 2022, the NACo Housing Task Force convened county government officials nationwide to illuminate the most critical housing challenges and opportunities from the county government perspective.

CO-CHAIRS

Hon. Kevin Boyce

Commissioner

Franklin County, Ohio

Hon. Sherry Maupin

Commissioner

Valley County, Idaho

MEMBERS

Hon. Monique Baker McCormick

Commissioner

Wayne County, Mich.

Hon. Rod Beck

Commissioner

Ada County, Idaho

Hon. Mack Bernard

Commissioner

Palm Beach County, Fla.

Hon. Matt Calabria

Commissioner

Wake County, N.C.

Hon. Reuben Collins

Commissioner President

Charles County, Md.

Brantley Day

Community Development Director

Cherokee County, Ga.

Hon. Richard Desmond

Supervisor

Sacramento County, Calif.

David Dunn

Executive Director, Housing Redevelopment Authority

Olmsted County, Minn.

Hon. Richard Elsner

Commissioner

Park County, Colo.

Hon. Bill Gravell

Judge

Williamson County, Texas

Hon. George Hartwick

Commissioner

Dauphin County, Pa.

Hon. Carlotta Harrell

Chair of the Board of Commissioners

Henry County, Ga.

Hon. Deb Hays

Commissioner

New Hanover County, N.C.

Terry Hickey

Director of Housing and Community Development

Baltimore County, Md.

Hon. Eileen Higgins

Commissioner

Miami-Dade County, Fla.

Hon. Ann Howard

Commissioner

Travis County, Texas

Hon. Alicia Hughes-Skandjis

Assembly Member

City and Borough of Juneau, Alaska

Mary Keating

Director of Community Services

DuPage County, Ill.

Hon. Marilyn Kirkpatrick

Commissioner

Clark County, Nev.

Graham Knaus

Executive Director

California State Association, Calif.

Hon. Jennifer Kreitz

Supervisor

Mono County, Calif.

Hon. Barry Moehring

Judge

Benton County, Ark.

Hon. Ken Hughes

Supervisor

Essex County, N.Y.

Hon. Larry Nelson

Supervisor

Waukesha County, Wis.

April Norton

Housing Director

Teton County, Wyo.

Patrick Alesandrini

Chief Information Officer

Hillsborough County, Fla.

Hon. Renee Robinson-Flowers

Commissioner

Pinellas County, Fla.

Hon. Josh Schoemann

County Executive

Washington County, Wis.

Hon. Lisa Schuette

Supervisor

Carson City, Nev.

Hon. Bill Truex

Commissioner

Charlotte County, Fla.

Hon. Nora Vargas

Supervisor

San Diego County, Calif.

Appendix C: Subject Matter Experts

Throughout the work of the task force, several experts from across state, federal, local, private and nonprofit partners provided knowledge and insights on local housing policy. The following is a non-exhaustive list of the housing experts that engaged with, advised or otherwise were involved in task force activities.

The White House

Dan Hornung, Special Assistant to the President

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

Sarah Brundage, Senior Advisor for Housing Supply and Infrastructure

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

Alene Tchourmoff, Senior Vice President for Community Development and Engagement

https://www.minneapolisfed.org/

Dallas County

Jonathan Bazan, Assistant County Manager

Elizabeth Allen, Assistant Director of Planning & Dev.

City of Dallas

Lawrence Agu, Chief Planner

Builders of Hope Community Development Corporation – Dallas

James Armstrong III, President & CEO

Catholic Housing Initiative - Dallas

Shannon Ortleb, COO

International Business Machines (IBM)

Ken Wolsey, Partner for Health and Human Services

Dan Chenok, Executive Director, Center for The Business of Government

https://businessofgovernment.org/

National Association of Home Builders

Karl Eckhart, Vice President, Intergovernmental Affairs

Key Banc Capital Markets

Sam Adams, Managing Director

https://www.key.com/businesses-institutions/industry-expertise/keybank-capital-markets.html

American Enterprise Institute (AEI)

Howard Husock, Senior Fellow for Domestic Policy Studies

Aspen Institute

Tim Shaw, Policy Director

Katherine McKay, Associate Director

https://www.aspeninstitute.org/

Brookings Metro

Jenny Scheutz, Senior Fellow

https://www.brookings.edu/program/brookings-metro

Harvard Joint Center for Housing

Dr. Chris Hebert, Managing Director

Niskanen Center

Alex Armlovich, Senior Housing Policy Analyst

Andrew Justus, Housing Policy Analyst

https://www.niskanencenter.org/

The Terner Center for Housing Innovation

Ben Metcalf, Managing Director

https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/

The Urban Institute

Yonah Freemark, Research Associate Madeline Brown, Senior Policy Associate

Appendix D: Glossary Of Key Housing Terms

An independent residential living unit that shares the same parcel of land as a single-family home, such as an english basement, carriage-house apartment, in- law suite or similar structure.

Housing units that are income-restricted, typically based on parameters around the area median income of a jurisdiction or region, typically referred to as public housing units.

A measure that represents the total amount of expected interest charged on a loan, mortgage or other debt mechanism over the course of one year, including compound interest. It takes into account the interest rate and the frequency at which it is compounded.

Appraisal gap financing provides a grant or a loan to cover the gap between appraisal and market value. It is typically used for homes that need some amount of rehabilitation.

The midpoint of a specific area’s income distribution and is calculated yearly by the Department of Housing and Urban Development. This calculation is used to disburse many federal, state and local programs, including Housing Choice Vouchers, and analyze home-cost burdens and affordability.

Loans that have lower annual percentage rate yields than those available in the private market. These loans lessen the debt needed to finance a particular housing development or rehabilitation project.

Building codes outline minimal standards for building features such as structural integrity, mechanical integrity (water supply, light, ventilation), fire prevention and control, and energy conservation. Building codes are generally determined at the state, national, and international levels.

An authorization that must be granted by a government or other regulatory body before construction or renovation can legally occur.

A competitive grant program designed to attract private capital to the development, preservation, rehabilitation, or purchase of affordable housing for low-income families.

An annual grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to states, cities, and counties to develop decent and affordable housing and expand economic opportunities for low- and moderate-income persons.

Private or non-profit organizations that own land on behalf of a community, creating affordable housing units and maintaining their affordable status in the future. The community land trust owns the land and sells the housing unit to a buyer, along with a ground lease that specifies the terms under which the home may be sold to the next purchaser. Under community land trusts, purchasers own the building and lease the land from the community land trust.

Limits how an owner can use their property. In this case, it mainly refers to the deed restrictions that place a temporary – usually a few decades – limit on the subsequent sale price and eligibility of future buyers. This aims to preserve housing units’ affordability into the future.

Refers to the number of housing units per land unit in a given area. Low-density housing areas are typically composed of single-family homes, whereas high-density areas encompass various housing typologies, including but not limited to multi-story buildings featuring multiple units.

A policy or tax incentive allowing developers to build more units than what would normally be allowed under the zoning code, in exchange for a commitment that developers include a certain number of below-market units in the development.

The federal agency responsible for national policy and programs that address America’s housing needs, improve and develop the Nation’s communities, and enforce fair housing laws.

Capitol that the buyer pays upfront in a housing transaction. Down Payments typically range from as little as 3% of the purchase price to as much as 20% of the purchase price.

Funds for affordable housing that are typically used for a large, one-time investment. These contrast with dedicated revenue sources, which provide smaller amount of funding over a longer period.

A grant from HUD to states and localities that communities use (often in partnership with local nonprofit groups) to fund affordable housing construction, acquisition, and/or rehabilitation. It is the largest federal block grant designed exclusively to create affordable housing for low- income households.

Access to reasonably priced, fair-quality housing; typically around 30 percent of an individual's total monthly income. Policymakers consider households that spend more than 30 percent of income on housing costs to be housing cost burdened.

A governmental body that governs aspects of housing, often providing support services for low-income residents and administering federal housing programs such as the Fair Choice Housing Voucher program.

HUD-administered program that helps low-income individuals and families fund affordable, safe housing in the private rental market. Participants receive a voucher that pays for a portion of their rent, helping to bridge the gap between the fair market rent and what the tenant can afford.

A one-time fee levied by local governments designed to offset the additional cost a housing unit has on community infrastructure.

Policies that create dedicated affordable housing units by requiring, encouraging or incentivizing developers to include a specified share of below-market units as part of market-rate rental or homeowner developments.

Entities such as publicly traded corporations, LLCs, LLPs, and private equity funds or real estate investment trusts (REITs) that possess housing or land as an asset. In recent years, institutional investors have represented a growing share of the single-family housing market.

A form of taxation based on the value of the land, rather than the housing unit. Under this system, a single- family lot would be taxed the same as a multi-family lot.

A form of impact fees that link the production of market-rate housing to affordability, charged on non-residential developments such as retail stores, industrial or manufacturing facilities, and other commercial projects.

A tax incentive for developers to construct or rehabilitate affordable rental housing for low-income households. It has supported the construction or rehabilitation of around 110,000 affordable rental units each year.

Homes that are pre-fabricated and transported to the desired location. These homes can be built much quicker than traditional houses, making them cheaper in comparison.

“Not in my backyard” is a phenomenon in which residents of a neighborhood are opposed to a new development such as affordable housing, believing that it will change their community for the worse.

Range of housing typologies focusing on form and scale that fit between single-family detached homes and mid-to-high-rise apartment buildings. Some examples include townhomes, duplexes, and triplexes.

A one-time tax or fee imposed by a state or local jurisdiction on the transfer (sale or purchase) of real estate property. The cost of this tax is based on the price of the property transferred to the new owner. Exact laws regarding these taxes vary by locality, in some areas the seller is responsible for payment while others may not even charge transfer taxes.

Laws limiting how much landlords can charge for rent to keep the property affordable.

An evolution of rent control, rent stabilization regulates the rate at which rent levels can increase.

The required distance that a housing unit must be from the front, sides, and back of the property line.

A living space that is not intended for long-term occupancy, such as an Airbnb or Vrbo.

Transit Oriented Development is a growing trend in creating vibrant, livable, sustainable communities. The trend aims to develop walkable, mixed-use communities around high quality public transit systems in hopes of eliminating car dependence and the various costs that arise from it.

Housing affordable to households earning between 60 and 120 percent of the area median income (AMI). This type of housing mainly targets middle-income workers such as police officers, teachers, healthcare workers, and similar professions.

“Yes in my backyard” is the opposite of NIMBY. The YIMBY movement is a pro-housing movement that supports increasing the supply of housing and the creation of zoning ordinances that would allow denser housing to be produced.

Appendix E: Endnotes

- NACo Analysis of U.S. Census Bureau - American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimates, 2017-2021 (Tables B25091 and B25070).

- U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Median Sales Price of Houses Sold for the United States [MSPUS]; 2023.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Rent of Primary Residence in U.S. City Average [CUUR0000SEHA]; 2023.

- Realtor.com, Housing Inventory: Active Listing Count in the United States [ACTLISCOUUS], retrieved from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; 2023.

- Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, The State of the Nation’s Housing, 2023.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Home Repairs Needs and Costs Estimates, 2023.

- Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, The State of the Nation’s Housing, 2023.

- RealtyNewsReport.com “Home Builders Face Delays in the Costly Supply Chain Strain” May 2, 2022.

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Accessibility in Housing 2019 American Housing Survey; 2022.

- “Calculating the Cost of Weather and Climate Disasters” (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2023).

- Elijah De La Campa and Vincent J. Reina, “How has the Pandemic Affected Landlords?” (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, 2021).

- Michal Grinstein-Weiss, Brinda Gupta and others, “Housing Hardship Reach Unprecedented Heights During the COVID-19 Pandemic” (Brookings Institute, 2020).

- Frank Morris, “The Pandemic has Sparked Rising House Prices Across the Rural U.S.” (National Public Radio, 2021).

Featured Initiative

NACo Housing Task Force

NACo’s Housing Affordability Task Force examined housing challenges and highlighted county-led solutions to address the housing affordability and inventory crisis. The task force identified intergovernmental and public-private strategies to enhance housing affordability and stability.