Primary Government

Primary Government: A local government with independent authority to determine its own budget, levy taxes, and issue bonds.[14]

Dr. Emilia Istrate, Cecilia Mills & Daniel Brookmyer

NACo POLICY RESEARCH PAPER SERIES • ISSUE 4 • FEBRUARY 2016

Printable PDF of Executive Summary

Counties provide essential services to 308 million residents across the country to keep communities prosperous, safe and secure. Creatures of the states, county governments operate in a constrained financial environment, conforming to state and federal mandates and limited by state caps on their ability to raise revenue. Understanding the diversity of county financial reporting and data is a first step towards examining national trends in county financial health. An analysis of 3,053 county financial reports reveals that:

Most state and local governments follow generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), standards of accounting and financial reporting developed by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB), an independent, private organization. Thirty-two (32) states require counties to follow GAAP and 295 counties in another 13 states and the District of Columbia choose to file their financial reports according to GASB standards, as of November 2015. As a result, almost three-quarters (71 percent) of counties report their annual financial information following GASB standards in the format of basic financial statements and on an accrual basis of accounting.

Almost a fifth (19 percent) of counties use a financial reporting format decided by their state and other comprehensive basis of accounting (OCBOA) different from GASB standards. Nine states (Ark., Ind., Kan., Ky., Mo., N.J., Okla., Vt. and Wash.) ask counties to follow an alternative method of financial reporting and accounting to GAAP. The state determines the framework, including measurement, recognition, presentation and disclosure requirements of the county financial reports. Another ten percent of county governments use basic financial statements approved by GAAP, but they do not use accrual accounting. Most of these county governments are on the smaller side; 94 percent of them have less than 50,000 residents.

CAFRs are financial reports that follow the GASB standards and have more information, intended to provide a more robust financial and historical context of the county government. A CAFR’s additional discussions and analyses of county trends and statistical data add to the picture of a county’s financial standing. Bond rating agencies and bondholders use the additional information from a CAFR to assess the investment risk of the county government. Eighty-one percent of large counties — with more than 500,000 people — report using a CAFR. CAFRs are not exclusive to large county governments, but counties more likely to issue municipal bonds on a regular basis.

Understanding county financial reporting helps comprehend how counties function and deliver services to their constituents. Counties constantly balance serving residents while meeting the demands of state and federal mandates. The variation in financial reporting among counties nationwide shows the diversity of state regulatory requirements, county needs and the staffing and administrative capacity of county governments.

Counties provide essential services to 308 million residents across the country to keep communities prosperous, safe and secure. Creatures of the states, county governments operate in a constrained financial environment, conforming to state and federal mandates and limited by state caps on their ability to raise revenue. Understanding the diversity of county financial reporting and data is a first step towards examining national trends in county financial health. It also lays the foundation for future research about the impact of changes in state financial reporting standards for county governments. This study provides a comprehensive, national view of the variations among county governments in terms of financial reporting, as well as state and other standards with which counties have to comply for financial reports. This analysis intends to educate a policy audience evaluating the parameters of fiscal transparency placed on counties.

Understanding the diversity of county financial reporting and data is a first step towards examining national trends in county financial health.

Most state and local governments follow generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), standards of accounting and financial reporting developed by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB), an independent, private organization. The accounting and capital markets recognize GASB as the official source of GAAP for state and local governments.[1] State auditors or independent public accountants audit county financial statements through the lens of GASB standards. If a county’s financial report is fairly and appropriately presented in accordance with GAAP, the county receives an unqualified opinion. An adverse opinion from auditors can negatively affect a county’s borrowing costs.

GASB periodically issues new accounting standards that state and local governments observing GAAP have to implement. For example, GASB Statement No. 68 reporting standard issued in June 2012 set new requirements for government employers with defined benefit pension plans to include a net pension liability in their financial report balance sheet for fiscal years after June 15, 2014.

The accounting and capital markets recognize GASB as the official source of GAAP for state and local governments.

County financial reporting, however, extends beyond GAAP. Depending on state requirements, county governments may use alternative methods of financial reporting and accounting to GASB standards, ultimately affecting how and what financial activities counties report to stakeholders and the public. As a result, financial reporting may differ substantially among counties across the country. This study examines state requirements for county financial reporting, as well as the types of financial statements and accounting methods county governments employ. The immediate goal is to provide an understanding of the diversity of financial reporting among counties, how financial data differs among county governments and the extent of observance of GASB standards. This report intends to create a foundation for future policy research on county finance and transparency.

Thirty-two (32) states require counties to follow GAAP through statute and 295 counties in another 13 states and the District of Columbia choose to file their financial reports according to GASB standards.

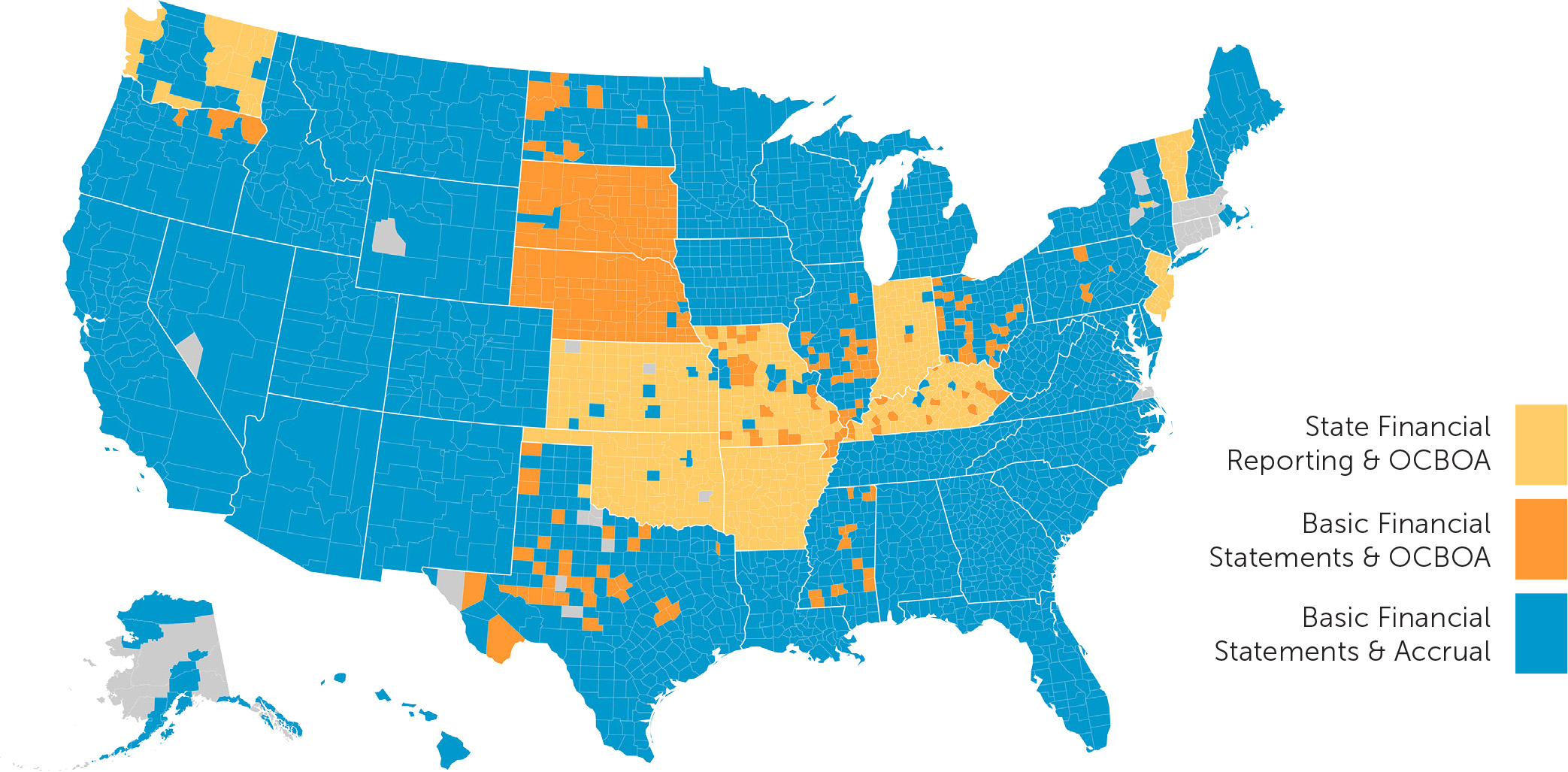

County governments apply GASB standards either because the state requires them to do so or to receive a favorable audit. Thirty-two (32) states require counties to follow GAAP through statute and 295 counties in another 13 states and the District of Columbia choose to file their financial reports according to GASB standards (See Map 1). Western states are the most likely to require counties to follow GASB standards. All but two Western states – Washington and Nebraska – require counties to report according to GAAP issued by GASB. In contrast, about half of Midwest states require their counties to use GAAP when filing annual financial reports. In these 32 states, county governments follow the GAAP approved format of the report (basic financial statements) and the accounting method (accrual basis) (See Appendix for more explanation of basic financial statement and accrual basis of accounting).

As of November 2015

States require counties to produce an annual financial report audited by a third party. Most states specify the accounting methods and financial reporting standards for counties either by statute or by giving authority to state comptrollers (or similar positions) to choose the financial reporting standards. In some instances, the state acts as the independent third party auditor for the county governments. For example, the Alabama Examiner of Public Accounts audits the accounts, books and records of all county offices.[2] In North Dakota, the Office of the State Auditor performs the audits for all 53 counties in the state.[3] Other states, like Texas, are more nuanced. The Texas Local Government Code determines the audit procedure based on the county population size. Counties with more than 350,000 residents must have an independent audit conducted by a third party every year. County governments in counties with populations between 40,000 to 100,000 residents must appoint a county auditor. The smaller county governments, in counties with less than 25,000 residents, can pool their resources with other county governments to hire a public accountant to conduct these audits.[4]

Nine states ask counties to follow an alternative method of financial reporting and accounting to GAAP. These nine states (Ark., Ind., Kan., Ky., Mo., N.J., Okla., Vt. and Wash.) use a regulatory basis of accounting, in which the state determines the framework, including measurement, recognition, presentation and disclosure requirements of the county financial reports. They also use other comprehensive basis of accounting (OCBOA), such as cash basis of accounting and different from the GASB accrual bases of accounting (See Key Terms for definitions).

Most regulatory states allow counties to choose between the state requirements and GASB standards.

Most regulatory states allow counties to choose between the state requirements and GASB standards. About 8 percent of counties in these states elect to follow GASB standards (both the format of the financial report and method of accounting), to increase their chances of receiving a favorable audit. While states may allow counties to choose GAAP over the state regulatory basis, in some cases counties need additional measures to adopt their preferred accounting standards. For example, counties in Oklahoma and Washington choose between GASB and the statutory alternative without any additional preliminary approval from the state.[5] Alternatively, Kansas counties adopt the state regulatory basis of accounting by county board resolution.[6] As of November 2015, 96 out of 105 Kansas counties have adopted state reporting standards by board resolution. Large counties in regulatory states are more likely to follow GASB standards. Ten of the 20 large counties in regulatory states — with more than 500,000 residents — report according to GAAP, while a quarter of mid-sized counties — with 50,000 to 500,000 residents — and 1 percent of small counties do so. Most of the large counties that do not follow GASB are in New Jersey, a state with strict requirements for counties to follow the state reporting standards.

The remaining seven states with county governments (Ala., Del., Ill., Neb., N.Y., S.C. and S.D.) have minimum requirements on county financial reporting. Adherence to GAAP in these counties is more of a tradition than a state requirement. The majority of the counties in these seven states elect to organize their financial statements according to GASB standards, including all large counties. For example, Delaware and Nebraska do not have a state statute or policy instructing counties how to report their annual financials.[7] Instead, counties choose to report according to GAAP to increase their chances for favorable reviews by bond rating agencies.

Annual and Biennial Audits of County Financial Reports. The time of the release of a county financial statement varies depending on the period of the fiscal year in the county and other factors. In some states, such as Arizona, the county fiscal year runs from July 1 of the preceding calendar year to June 30 of the current calendar year. For example, Maricopa County, Arizona’s 2007 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) reflects the county financial activity occurring between July 1, 2006 and June 30, 2007.[8] In other states, like Minnesota, the fiscal year for financial reporting matches the calendar year, meaning that a county financial report reflects fiscal activity from January 1 to December 31 of the given calendar year. Further, the audits of some of the county financial reports are not released annually. In 17 states, a state auditing agency conducts all or some of the audits of county financial statements. In the rest of the counties in these states and around the country, a county auditor or an independent auditor perform the audit of the county financials. In some states, such as Missouri and North Dakota, the state auditor conducts the majority of county financial statement audits and release biennial audits. In South Dakota, the State Auditor releases biennial audits mostly for smaller counties.[9]

In total, 16 states either ask counties to report using alternative methods to GAAP or allow county financial reporting to develop by tradition.

Under the jurisdiction of their respective states, county governments file annual financial reports in accordance with state regulations. While the vast majority of states require adherence to GAAP for county financial reporting, GASB standards are not the only paradigm for conveying county financials. In total, 16 states either ask counties to report using alternative methods to GAAP or allow county financial reporting to develop by tradition. The variation of state requirements lends to the diversity of county financial reporting.

GASB standards are predominant among county governments, with almost three-quarters (71 percent) of counties reporting their annual financial information in the format of basic financial statements and on an accrual basis of accounting, as of November 2015 (See Appendix for more information of GASB standards on the format of the financial report and method of accounting). Large counties — with more than 500,000 residents — are the most likely to follow GAAP for annual financial reporting (92 percent of large counties). The majority of counties of smaller sizes — 87 percent of medium sized counties, with populations between 50,000 and 500,000 and 64 percent of small counties, with less than 50,000 residents — also apply GASB standards.

Not all counties, however, follow GAAP. Almost a fifth (19 percent) of counties use a financial reporting format decided by their state (henceforth, “regulatory basis statements”) and other comprehensive basis of accounting (OCBOA) and ten percent of county governments use basic financial statements, but not accrual accounting (they use OCBOA).

As of November 2015

The state determines the funds and methodology to be used primarily for compliance with legal provisions and budgetary restrictions.

State-specific regulatory financial reporting requirements and OCBOA are the standard for 19 percent of county governments. The overwhelming majority are in all nine of the regulatory states (Ark., Ind., Kan., Ky., Mo., N.J., Okla., Vt. and Wash.), mostly in the Midwest and South. All the counties in Ark., N.J. and Vt. file reports in accordance with state regulatory requirements. They do not employ either the GAAP format of financial statements (basic financial statements) or the method of accounting (accrual). Instead, they use the format decided by their state and accounting bases other than accrual. The state determines the funds and methodology to be used primarily for compliance with legal provisions and budgetary restrictions.[10] Most of these county governments are on the smaller side; 83 percent of them have less than 50,000 residents. However, nine large counties (all large counties in N.J.) also implement this type of financial reporting. Bergen County, N.J. is the largest county filing a regulatory basis statement, with more than 933,000 residents in 2014.

While state requirements for accounting methods and formats for county financial reports vary widely, the one commonality is the requirement that counties report by fund type. Unlike government-wide statements that disaggregate financial information by fund and present primary government financial activities as a whole, the state regulatory requirements examine county government funds as separate, distinct accounts that cannot be added together. The funds that counties report differ according to state regulations. For example, Oklahoma counties must produce financial statements that present only the funds representing 10 percent or more of the county’s total revenue.[11] Indiana and Missouri counties must report all county funds as separate line items.[12] Meanwhile, Kentucky counties must report their funds in statements as budgeted and demonstrate that fund expenditures did not exceed the appropriated amounts in accordance with state budgeting and financial reporting laws.[13]

Differences with GASB Basic Financial Statements. The state regulatory basis statements differ from basic financial statements done on an accrual basis of accounting in a number of ways. While the state regulatory statements present the primary government financials by fund type, the GASB-approved statement of activities aggregates the financial activity of the county by major function/program. The regulatory basis statements blend the enterprise revenues within funds and do not delineate business-type activities as in government-wide financial statements. Another distinct difference is the absence of the financials of county component units from the regulatory basis county financial statements. The component units of New Jersey counties, such as vocational school districts, economic development authorities and utilities authorities, produce separate financial reports from the county financial statement. The regulatory basis statements do not include management’s discussion and analysis, as the basic financial statements do.

These county governments also use other comprehensive bases of accounting (OCBOA) that are different from GAAP standards. These include a cash basis of accounting, which recognizes revenues when transaction occurs and expenses when paid for, and a modified cash basis accounting, which combines cash basis and accrual basis of accounting. Modified cash basis of accounting uses accrual accounting for expenditures and cash basis for revenues (See Key Terms for definitions). These methods are different from the accrual basis of accounting. In the case of the accrual method of accounting, when a county receives an invoice from an outside party, for example, the county records the full expense of the invoice before any payment is made by the county to the outside party. With the cash basis of accounting, however, the county would record the invoice as an expense only when the county paid the invoice in cash. The accounting literature is still debating the benefits and costs of using different methods of accounting. Counties may use OCBOA for several reasons. Small county governments may view GAAP reporting as less useful for budgetary and administrative decision-making.[16] Preparing financial statements on an accrual basis of accounting may be labor intensive for counties that track their annual financial activities on a cash basis. Some voices in the accounting literature consider cash and modified cash basis of accounting easier to understand, verify and execute.[17]

A small percentage of counties report their financials in the form of basic financial statements, but use OCBOA for accounting.

A small percentage of counties (10 percent) report their financials in the form of basic financial statements, but use OCBOA for accounting. The overwhelming majority of these counties (94%) have less than 50,000 residents. The vast majority of them are in the seven states with minimum financial reporting standards (Ala., Del., Ill., Neb., N.Y., S.C. and S.D.). Further, 44 counties in regulatory states elect to report according to GASB standards in the form of basic financial statements, but do not use the accrual method of accounting that is required by GAAP. Forty-three of these counties are in Kentucky and Missouri. Marion County, Ind. — with a population of 934,243 — is the other county in a regulatory state that uses OCBOA for its financial reports. Compliance with GAAP is optional for counties in all these states. Even though these counties use basic financial statements — and have a statement of net position and statement of activities — their financials are not comparable with those counties that use basic financial statements and accrual basis of accounting. Because they use OCBOA (mainly cash basis accounting), the amounts shown for primary government functions in the statement of activities and net position do not include the costs and revenues incurred during the fiscal year that have outstanding payments or receivables. For example, their statement of net position would not include any depreciation of county-owned properties or investments earned for post-employment benefits but not yet paid.

About a third of county governments do not use accrual basis of accounting, relying on OCBOA instead. Midwestern counties are most likely to use other methods of accounting than any other region (See Figure 1). Forty-three (43) percent of Midwestern counties report using other methods of accounting than accrual; these are mostly counties on the smaller side (less than 50,000 residents). While 21 percent of Northeastern counties report with alternative methods of accounting to GAAP, more than a third of large counties in this region use OCBOA because of New Jersey State’s strict requirements for counties. In contrast, all the Western and Southern large county governments use accrual basis of accounting, as approved by GASB.

Percentage of County Governments by Region that Use OCBOA

GAAP is the standard for 71 percent of counties, but not all. About 19 percent of counties financially report according to state regulatory standards in order to meet the financial and budgetary requirements of their state governments. Another fraction of counties use the basic financial statements format required by GASB but use OCBOA to suit county needs. The variation in financial reporting among counties nationwide shows the diversity of state regulatory requirements, county needs and the staffing and administrative capacity of county governments.

The Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) and GASB consider Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports (CAFRs) to be the most thorough version of financial reporting. These financial reports have to fulfill GASB standards and GFOA requirements, as established by GFOA’s Certificate of Achievement for Excellence in Financial Reporting Program. They are expanded basic financial statements on an accrual accounting basis, intended to provide a more robust financial and historical context of the county government. Besides the basic financial statements, a CAFR has a defined introductory section — table of contents, letter of transmittal and organizational chart for the county government — intended to familiarize the reader with the report. Further, it includes a statistical section with additional financial and statistical data, such as financial trends, debt capacity and demographics and economy, relevant to understanding the county financial standing. CAFRs are not required, but encouraged by GASB and GFOA as a best practice.

A quarter of county governments following GAAP compile CAFRs.

A quarter of county governments following GAAP compile CAFRs. County governments opt to report their financial statements as a CAFR for a couple of reasons. A CAFR’s additional discussions and analyses of county trends and statistical data add to the picture of a county’s financial standing. Bond rating agencies and bondholders use the additional information from a CAFR to assess the investment risk of the county government.[18] By completing a CAFR, a county can submit their audited financial statement for consideration for the Government Financial Officers Association (GFOA)’s Certificate of Excellence in Financial Reporting. Receiving GFOA’s certificate increases the chances that credit agencies or other stakeholders may consider the county’s financials positively.

As of November 2015

The 567 counties that issue CAFRs are found across 39 different states and the District of Columbia.

The 567 counties that issue CAFRs are found across 39 different states and the District of Columbia (See Map 3). Western and Southern counties are most likely to use a CAFR for financial reporting. The majority of counties in five states (Calif., Del., Hawaii, Md. and N.C.) use CAFRs. Hawaii is the only state in which all the counties release a CAFR for their annual financial report. The counties that report CAFRs are also in regulatory states, but in much smaller numbers. Three percent of counties in states with regulatory reporting requirements (Kan., Ky., Mo. and Okla.) use CAFRs, half of which are mid-sized counties (populations between 50,000 and 500,000). None of the counties in the remaining six non-regulatory states (Ala., Miss., N.H., S.D., W.Va. and Wyo.) report with CAFRs.

Larger county governments are more likely to compile CAFRs (See Figure 2). Releasing a CAFR helps counties that issue municipal bonds more regularly. The larger county governments are more likely to issue municipal bonds to fund capital investment and they also have larger tax bases to back general obligation bonds. Often, large counties have in-house staff that structures the county’s municipal bonds.[19] Eighty-one percent of large counties — with more than 500,000 people — report using a CAFR. In comparison, 43 percent of mid-sized counties (with populations between 50,000 and 500,000) compile this extended financial report. Only 5 percent of small counties (with less than 50,000 people) issue CAFRs. Cheyenne County, Colo. is the least populous county in the country compiling a CAFR (1,871 residents in 2014). Regardless of size, counties in the West and South are most likely to report with a CAFR. About a fifth of counties in each of these regions report CAFRs (See Figure 2). Further, the majority (51 percent) of western mid-sized counties use CAFRs. Few of the Midwestern counties report with CAFRs, with the exception of their large counties; 96 percent of large counties in the Midwest use this extended financial report.

Percentage of County Governments by Region that Report with CAFRs

Counties that seek to receive awards and favorable ratings from credit and bond rating agencies elect to report a CAFR. These expanded basic financial statements provide a robust financial and historical context of the county government. CAFRs are not exclusive to large county governments, but counties who issue municipal bonds more regularly are more likely to release CAFRs.

Understanding county financial reporting helps comprehend how counties function and deliver services to their constituents. As local governments under the jurisdiction of the states, counties observe accounting procedures designated by their state legislatures and statutes. Often, states defer to GASB standards for rules for county financial reporting. While the majority of counties follow GASB, some states have different reporting requirements for their counties. County adherence to state and GASB standards and the amount of information disclosed in their financial reports may influence county government creditworthiness.

This study shows the diversity of financial reporting, state rules for county financial reporting and county financials among county governments. A majority of counties follow GASB standards when compiling their annual financial reports, primarily because their state requires adherence to GAAP. In addition, about 10 percent of counties use cash or modified cash basis of accounting (OCBOA), methods of accounting different from GASB standards, while reporting with GASB approved formats (basic financial statements). Finally, close to 20 percent of county governments follow state specific methods of accounting and reporting that are different from GASB standards.

Counties constantly balance serving residents while meeting the demands of state and federal mandates. Ongoing changes to GASB standards affect the majority of counties in how they report their annual financials. An understanding of the nature of the county financial data provides the basis for future policy research in county finance.

County governments that follow GASB standards for their financial reports for audit review compile basic financial statements and mainly use an accrual basis of accounting.[20] As standardized by GASB Statement No. 34 in 2002, the basic financial statements include fund financial statements that report on the county’s major funds; government-wide financial statements that report on the county government as a whole; and notes to financial statements.

Fund financial statements report county revenues and expenditures by major fund type and non-major fund type. Major funds include governmental and enterprise funds. While the governmental funds are the chief operating funds of the county government, enterprise funds report the financials on county activities that charge user fees. Non-major funds represent governmental and enterprise funds that make up less than 10 percent of the funds in that category (governmental or enterprise) and less than 5 percent of the combined total of governmental and enterprise funds. Separate fund statements report internal service funds (a type of proprietary fund for cost reimbursements for goods or services within county government) and fiduciary fund information (the pension, investment and private-purpose trusts of the county government and agency funds).

Government-wide statements report the totality of the financial activities of the governmental and enterprise activities of the primary government and component units — the legally separate entities for which the primary government is fiscally accountable. Governmental activities are services primarily funded through a dedicated tax revenue stream, while enterprise (or business-type) activities are funded by user fees (such as road tolls, park entry fees and parking charges). These statements show the financial sustainability of the county government as an entity and the change in the county’s net position over the previous fiscal year.[22]

The government-wide statements include a statement of net position and a statement of activities. The financial reports reflect an economic resources measurement focus, meaning that the organization of the statements and method of accounting allow for the examination of all of the revenues, expenditures, assets and outstanding balances of the county government. The statement of activities includes revenues, expenses, gains and losses, while the statement of net position reports the county assets and liabilities. Each statement distinguishes between the governmental and business-type activities of the primary government.

County expenditures. The statement of activities shows county expenditures as expenses for primary government functions (such as judicial and public safety programs) and business-type activities (such as waste disposal and collection and permitting services) (See Table 1). The expenditure categories differ from county to county, depending on the primary government’s functions and programs, as well as the county’s business-type activities. For example, the fiscal year 2013 statement of activities of Prince George’s County, Md., presents seven primary governmental activities, such as “health and human services,” “public safety” and “infrastructure and development.” Alternatively, Calvert County, Md., financial statement for fiscal year 2013 listed 11 different primary governmental activities and reported separately “social services” and “health and hospital,” instead of “health and human services.”

The statement of activities also shows separately the expenses of the county’s component units – legally separate entities for which the primary government is fiscally accountable, such as school districts, sanitary commissions and housing authorities (See Table A1). As legally separate entities, their expenses are not included in the county government’s expenses. Component units are distinctly apart from the primary government as they have their own appointed or elected members that decide their policy. For example, one of Broward County, Fla.’s component units is the Housing Finance Authority. The board of Broward County, Fla., Housing Finance Authority retains the authority to set the agency’s policies. However, the Broward County Board of Commissioners appoints the members of this board.[23]

County Revenues. Total county revenues include both revenue restricted to a specific activity (program revenues) and unrestricted county general revenues. The statement of activities links the expenditures of each governmental and business-type activity to their program revenue sources (See Table A1). The program revenue for an activity is the income generated by charges for services provided under that activity (“charges for services”) or intergovernmental grants and contributions restricted to meet operational or capital requirements (“operating grants and contributions” and “capital grants and contributions”). GASB standardizes these three types of program revenue and they appear regularly in the statement of activities of county governments that follow GAAP. However, the county government might not generate all the types of program revenue for each of its governmental and business-type activities. For example, in the fiscal year 2013 financial statement of Tuscaloosa County, Ala., none of the eight government functions reported program revenues generated from capital grants and contributions, whereas nearly half of the government functions in Shelby County, Ala., financial statement had associated revenues from capital grants and contributions in the county’s fiscal year 2013.

The statement of activities keeps track of the difference between expenses and program revenues separately for each of the governmental activities, business-type activities and component units. The total revenue of the primary government does not include the revenues from component units. County general revenues and transfers among county programs cover the difference, in case program revenues come short of expenses. The result is the change in net position of the county, which shows how the financial position of the government has changed over the fiscal year. Added to the net position from the beginning of the fiscal year, it yields the net position of the county government at the end of the fiscal year (See Table A1).

|

|

|

Program Revenues |

Net (Expense) Revenue and Changes in Net Position |

|||

|

FUNCTIONS/PROGRAMS |

EXPENSES |

CHARGES FOR SERVICES |

OPERATING GRANTS AND CONTRIBUTIONS |

CAPITAL GRANTS AND CONTRIBUTIONS |

PRIMARY GOVERNMENT |

COMPONENT UNITS |

|

Governmental Activities (examples): |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General government |

1 |

8 |

15 |

22 |

(8+15+22)-1 |

|

|

Public safety |

2 |

9 |

16 |

23 |

(9+16+23)-2 |

|

|

Transportation |

3 |

10 |

17 |

24 |

(10+17+24)-3 |

|

|

Environmental protection |

4 |

11 |

18 |

25 |

(11+18+25)-4 |

|

|

Economic and physical development |

5 |

12 |

19 |

26 |

(12+19+26)-5 |

|

|

Human services |

6 |

13 |

20 |

27 |

(13+20+27)-6 |

|

|

Workforce development |

7 |

14 |

21 |

28 |

(14+21+28)-7 |

|

|

Total Governmental Activities |

Total Expenses for Governmental Activities (1+...+7) |

Total Charges for Services for Governmental Activities (8+..+14) |

Total Operating Grants and Contributions for Governmental Activities (15+...+21) |

Total Capital Grants and Contributions for Governmental Activities (22+...+28) |

Total Program Revenues- Total Expenses for Governmental Activities |

|

|

Business-Type Activities (examples): |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Airport |

29 |

33 |

37 |

41 |

(33+37+41)-29 |

|

|

Permitting services |

30 |

34 |

38 |

42 |

(34+38+42)-30 |

|

|

Waste disposal and collection |

31 |

35 |

39 |

43 |

(35+39+43)-31 |

|

|

Water management |

32 |

36 |

40 |

44 |

(36+40+44)-32 |

|

|

Total Business-Type Activities |

Total Expenses for Business-Type Activities (29+...+32) |

Total Charges for Services for Business-Type Activities (33+...+36) |

Total Operating Grants and Contributions for Business-Type Activities (37+...+40) |

Total Capital Grants and Contributions for Business-Type Activities (41+...+44) |

Total Program Revenues - Total Expenses for Business-Type Activities |

|

|

TOTAL PRIMARY GOVERNMENT |

Total Expenses for Governmental Activities and for Business-Type Activities |

Total Charges for Services for Governmental Activities and for Business-Type Activities |

Total Operating Grants and Contributions for Governmental Activities and for Business-Type Activities |

Total Capital Grants and Contributions for Governmental Activities and for Business-Type Activities |

Total Program Revenues- Total Expenses for Governmental Activities and for Business-Type Activities |

|

|

Component Units (examples): |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Affordable housing (Housing Finance Authority) |

45 |

48 |

51 |

54 |

|

(48+51+54)-45 |

|

Landfill (Solid Waste Authority) |

46 |

49 |

52 |

55 |

|

(49+52+55)-46 |

|

Elementary and Secondary Education(School Board) |

47 |

50 |

53 |

56 |

|

(50+53+56)-47 |

|

TOTAL COMPONENT UNITS |

Total Expenses for Component Units (45+...+47) |

Total Charges for Services for Component Units (48+...+50) |

Total Operating Grants and Contributions for Component Units (51+...+53) |

Total Capital Grants and Contributions for Component Units (54+...+56) |

|

Total Program Revenues - Total Expenses for Component Units |

|

|

General Revenues (examples): |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Property taxes |

|

|

57 |

62 |

||

|

County income taxes |

|

|

58 |

63 |

||

|

Hotel-motel taxes |

|

|

59 |

64 |

||

|

Investment income |

|

|

60 |

65 |

||

|

Transfers |

|

|

61 |

66 |

||

|

Total General Revenues & Transfers |

|

(57+58+59+60+61) |

(62+63+64+65+66) |

|

||

|

Change in Net Position |

|

(Total Program Revenues- Total Expenses) + Total General Revenues and Transfers for Primary Government |

(Total Program Revenues- Total Expenses) + Total General Revenues and Transfers for Component Units |

|||

|

Net position – beginning of the fiscal year |

|

Net Position at the beginning of the current Fiscal Year for Primary Government |

Net Position at the beginning of the current Fiscal Year for Component Units |

|||

|

Net position – ending of the fiscal year |

|

Net Position at the beginning of the current Fiscal Year + Change in Net Position for Primary Government |

Net Position at the beginning of the current Fiscal Year + Change in Net Position for Component Units |

|||

Statement of Net Position. Accompanying the statement of activities, the statement of net position presents the county’s assets and liabilities of the primary government’s governmental and business-type activities, as well as the associated component units. County assets range from highly liquid cash and receivables to illiquid capital assets, like county owned buildings or trucks. The county’s outstanding liabilities delineate items such as accounts payable, deposits, dues within county government, to component units or other governments as well as non-current liabilities Amounts disclosed for liabilities show the remaining balances to be paid off. The difference between total assets and total liabilities is the county’s net position, which matches the end result within the statement of activities.

The items within the statement of net position may change depending on new GASB standards. For example, for fiscal years after June 15, 2014, GASB Statement No. 68 requires that all state and local governments must include within the statement of net position a “net pension liability,” as a new, separate liability (See Table A2). Previously, outstanding county employee pension obligations were sections within notes to financial statements and required supplementary information tracked by reporting the schedules when promised benefits are to be paid. Starting with fiscal year 2015 financial statements, the statement of net position will feature a “net pension liability” on an accrual basis with pending pension contributions expensed immediately. This change in GASB standards presents potential problems for county governments. Component units of county government and internal service funds may be adversely affected if there are significant employee cost allocations. Further, the added liabilities may be sufficiently large enough to negatively skew the value of the county’s ending net position.[25]

|

|

Primary Government |

|

||

|

|

Governmental Activities |

Business-type Activities |

Total Primary Government |

Component Units |

|

ASSETS |

|

|

|

|

|

Cash and cash equivalents |

$ 15,000,000 |

|

|

|

|

Net Receivables |

$ 5,000,000 |

|

|

|

|

Capital Assets |

$ 65,000,000 |

|

|

|

|

Total Assets |

$ 85,000,000 |

|

|

|

|

LIABILITIES |

|

|

|

|

|

Payables |

$ 300,000 |

|

|

|

|

Long-term Liabilities |

$ 70,000,000 |

|

|

|

|

Net Pension Liability |

$ 50,000,000 |

|

|

|

|

Total Liabilities |

$ 120,300,000 |

|

|

|

|

TOTAL NET POSITION |

($ 35,300,000) |

|

|

|

Source: California Committee on Municipal Accounting, “Implementing GASB Statement No. 68 Accounting and Financial Reporting for Pensions: A CCMA White Paper for Cal. Local Governments”(2015).

Notes to financial statements as required by GASB standards provide additional information about the government’s basic financial statements not conveyed by the government-wide or fund statements. Items include background of the county government, like the history or government structure, an explanation of the financial reporting standards applied to the statements, as well as the accounting methods used for government-wide and fund statements. Additional information may refer to the used methods of valuation and depreciation for county assets. Notes to financial statements also describe the primary government’s relationship to their associated component units.

Accrual Accounting Method. The GAAP observing counties employ an accrual accounting method, which requires the county to report expenses and revenues when expenses and revenues occur, not necessarily when cash is paid. For example, when a county receives an invoice from an outside contractor, the county records the full expense of the invoice before the county pays the invoice in full. The accounting literature is still debating the benefits and costs of using the accrual basis of accounting. Some financial organizations consider accrual basis of accounting as most reflective of county economic health.[27] Yet, some sources consider the accrual method of accounting to be overly complex, potentially leading to more errors by smaller governments and encouraging the overstatement of total revenues by inflating income and receivables.[28] County governments that follow GASB standards report the government-wide statements on an accrual accounting method. GASB approves the use of the modified accrual basis of accounting only for the governmental fund financial statements. Modified accrual accounting is a combination of the accrual and cash bases of accounting, which records revenues when they become available (cash basis accounting) and recognizes expenditures when incurred (accrual basis accounting). Governmental funds are expected to be used within a fiscal year since those funds provide direct services – such as public safety and capital improvements to roads.

As standardized by GASB, the elements of basic financial statements come together and tell the financial story of county governments. Presented as a whole, the fund financial statements, government-wide financial statements and notes to financial statements depict the economic resources of a county when earned, allowing users to understand the short and long-term financial narrative of county government.