Managing Disasters at the County-Level: A Focus on Public Health

Author

Blaire Bryant

Upcoming Events

Related News

Overview

In order to remain healthy, vibrant and safe, America’s counties must continue to strengthen their resiliency by building leadership capacity to better identify and manage risk. In 2017, there were 16 disaster events across the U.S. that resulted in losses exceeding $1 billion, including: 8 severe storms, 3 tropical cyclones, 2 floods, an extreme drought, a freeze and a major wildfire.1 In total, these events resulted in significant fatalities and economic losses: 362 people died, double the disaster-related death toll from last year; and over $306 billion in total damage was caused, $265 billion of which is attributed to Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria.2 In total, 813 counties were declared major disasters at least once by the federal government in 2017.3

45% of all local health departments responded to at least one all-hazards event in 2016

Disasters like these have a profound impact on the long-term public health of a community. It is critically important for county health departments to coordinate closely with their local offices of emergency management, as well as federal and state partners, to develop emergency and recovery plans that ensure the delivery of public health and medical services during a disaster. There are numerous factors for which county public health departments should plan, including but not limited to: lack of access to local hospitals; hospital and other first responder staff working overtime and/or unable to make it into work; lost or destroyed medications; food and pharmaceutical shortages; water and/or sewage treatment plants losing power or discharging untreated sewage; and the acute vulnerability of certain residents.4 Low income, disabled, elderly, immigrant, and chronically ill populations tend to be most adversely affected in disaster situations. They are typically the most impacted when access to critical treatment (dialysis, breathing machines, etc.) is lost, the most stressed during evacuation and temporary relocation, and most underprepared due lack of resources (insurance, mobility, alternative shelter, etc.). It is important for counties to understand those compounding effects.5

During the disaster recovery process, counties should prioritize managing basic health and safety concerns.6 In the short term, the most pressing concerns for county health departments are the prevention of potential injury and mortality due to a range of challenges, including: antibiotic resistant staph infections; flesh-eating bacteria; infection due to exposure to raw sewage or contaminated water; exposure to mold and mildew; increased mosquitos; and respiratory infections.7 In the long term, the major concern is to ensure the positive mental health of residents. Disasters and their associated aftereffects often lead to greater prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder, higher risk of alcohol and substance use and depression due to the loss of life and property and the challenge of coping with injuries sustained during the event.8

Types of Public Health Emergencies

- Disease outbreaks and incidents

- Natural disasters and severe weather

- Radiation emergencies

- Chemical emergencies

- Bioterrorism

- Pandemic influenza

Health and Safety Concerns

- Animals and Insects

- Illness and Injury

- Food and Water Safety

- Personal Hygiene and Handwashing

- Flood Water

- Carbon Monoxide Poisoning

- Power Outages

- Safe Clean Up

- Coping with Disaster or Traumatic Event

- Returning Home After a Disaster

This publication serves as a best practices guide for county leaders to better understand the intersections of public health protection and emergency management. The case studies included within spotlight counties whose public health departments have both taken a proactive approach to emergency management and have dealt with a high volume of disaster declarations over the past decade.

Working with Your State and Federal PartnersWhile local governments are the first responders to disaster events, they must work alongside their state and federal government partners. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has the legal authority for responding to public health emergencies at the federal level. HHS’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) – which was created post-Hurricane Katrina – leads the nation in preventing, preparing for and responding to the adverse health effects of public health emergencies and disasters. Within ASPR, the Office of Emergency Management (OEM) provides resources and expertise to state and local communities to help them prepare for public health and medical emergencies, and coordinate health and social services during disaster recovery by connected them to real-time information. Key OEM programs include the Hospital Preparedness Program, the Medical Reserve Corps, the Critical Infrastructure Protection Program and the National Disaster Medical System. Learn more about OEM and its programs. |

Population: 776,864

Square miles: 718

Background

Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, is one of the most disaster-prone counties in the United States. The county contains 14 municipalities and 22% of the state’s population. It has experienced 23 declared disasters in the last decade and 42 since 1964—the year that the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) began collecting disaster declaration data at the county-level.9 The county has been hit by, and recovered from, almost every type of emergency and disaster situation. As Oklahoma City-County Public Health’s (OCCHD) Public Health Protection Director of Phil Maytubby stated, “you name it; we get it.”10 The county has experienced 14 severe storms, 13 fires, 7 severe ice storms, 4 floods, 2 tornadoes, 1 hurricane, 1 human-caused event – the Oklahoma City bombing – and has started to experience earthquakes, although not yet at a magnitude that has led to a disaster.11

While disaster response had always been part of the county health department’s activities, it was the 1995 bombing that catalyzed the county’s active focus on public health emergency preparedness. Since 1995, OCCHD has built a strong emergency preparedness and response department which takes advantage of its robust federal, state and local partnerships. At the federal level, the county has strong relationships with both FEMA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – which administers several public health emergency preparedness funding streams.

The Effect of 9/11 on Disaster PreparednessFollowing 9/11, the federal government realized the impact of disasters on public health and developed the Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP) to help strengthen public health emergency preparedness by providing leadership and funding through grants and cooperative agreements – particularly HPP- Public Health Emergency Preparedness Cooperative Agreements. Learn more |

A Focus on Preparedness

The key to the county’s ability to keep bouncing back after a disaster has been the close relationships it has built with first responders at the local level. Staff have worked hard to develop a resilient, core working group – one that starts with the county’s emergency managers. OCCHD coordinates with all emergency managers within its jurisdiction – city and county – to plan and implement the public health portions of the city’s and county’s emergency operations plans. These plans are reviewed, updated and approved annually, and cover both response and recovery. Approximately once a month, all major stakeholders meet either informally or formally, including at meetings of the Oklahoma Emergency Management Association and the local senior advisory council for preparedness. Meeting frequently ensures everyone knows each other and understands their role more clearly when stationed together in the county’s emergency operations center (EOC).

Beyond the county emergency managers, OCCHD maintains close relationships with its local utilities. This is especially important during a disaster event, as medical facilities, grocery stores and water treatment plants – to name a few – need power to stay operational and protect public health. The health department also works closely with local business entities to establish working relationships and make sure they have plans in place for a variety of scenarios, including loss of power.

Another major group the county engages is their volunteer community, as organized local participation during the response phase can make or break recovery efforts. OCCHD primarily uses its local VOAD – volunteer organizations active in disaster – and Medical Reserve Corps for response and recovery efforts, and it does not allow unaffiliated volunteers to work on disaster sites. By only using affiliated volunteers, it ensures responders have been properly trained, understand the incident command structure and have had proper background checks.

The county’s Medical Reserve Corps has over 1,800 members, with both medical and non-medical backgrounds. Medical members of the corps include doctors and nurses, while non-medical members include individuals such as forklift drivers and animal rescuers. The county recruits members through targeted marketing to and presentations at local medical facilities, medical schools and nursing schools as well as engaging with students that come through the department as part of a practicum. Director Maytubby touts the Medical Reserve Corps as a low-cost solution to fill critical emergency response needs. Beyond helping with basic clean up and support during disaster response scenarios, the corps – and local VOAD – provides counseling and mental health services in the immediate aftermath until individual cases can be transferred to mental health professionals.

Trainings and ExercisesIt is important to run regular trainings and exercises to ensure that all first responders, whether county staff, volunteers or residents, understand the incident management system and are ready to respond when a disaster strikes. Every Oklahoma County volunteer is vetted and trained. Medical Reserve Corps members in particular are required to attend an introductory training, and can opt to attend more intensive trainings to work on specific response teams. These trainings occur often throughout the year. Response teams can be deployed both to local events as well as to events in other counties in response to requests through any Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC) agreements the county has in place. |

OCCHD works hard to ensure it has good coalitions put together for disaster response and recovery – like the Medical Reserve Corps – because questions get answered and needs fulfilled much faster if you know your fellow response community on a first name basis. For example, when a tornado hit the county and cut off all power to the local water and wastewater treatment plants, the county’s response community deployed effectively as a team to protect that infrastructure and prevent sewage from being released into a local river.

Beyond networking locally, Director Maytubby recommends networking with other communities who have set up preparedness models you would like to see adopted in your county. “I can’t emphasis enough the important of not recreating the wheel,” he said. Vector control for mosquitoes is one area on which Oklahoma County has worked with other county health departments – both to learn from their programs and share OCCHD’s efforts.

Lastly, OCCHD recommends having a Continuity of Operations Plan (COOP). COOPs help to ensure the execution of essential organizational functions and the fundamental duty of a department during all-hazards emergencies or other situations that may disrupt normal operations. Due to the sensitive nature of continuity plans and procedures, COOPs are typically classified as “For Official Use Only.” A COOP should: describe the readiness and preparedness of the organization and its staff; outline to whom it should be distributed; detail the process for activating and relocating (or not-relocating) personnel from the organization’s primary facility to its continuity site(s); identify the continuation of essential functions – and delineate responsibilities for key staff positions; identify critical communications and information technology (IT) systems to support connectivity during crisis and disaster conditions; and specify how the organization and its staff will return to normal operations. Ideally, a COOP also explains how it fits into other county plans. OCCHD finds them helpful in managing scarce resources during disaster response and identifying vital departmental functions that must continue regardless of a disaster – such as investigations into cases of infectious diseases like tuberculosis.

27% of local health departments use volunteers to respond to all-hazard events

Conclusion

If the overall goal of public health preparedness is to minimize the effects of disaster events on county residents and vital county utilities and facilities, it is imperative that counties have the proper plans and partnerships in place. Preparedness is a continuous process that requires regular evaluation and updating of local plans, procedures and protocols to reflect any changes to the county’s current physical and organizational environment. To ensure prompt and comprehensive coverage of county needs during a disaster, always remember to coordinate with local community partners (e.g. other local jurisdictions, Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster and faith-based organizations) and leading national response agencies (e.g. FEMA and the Red Cross).

Population size: 4,589,928

Square miles: 1,703

Background

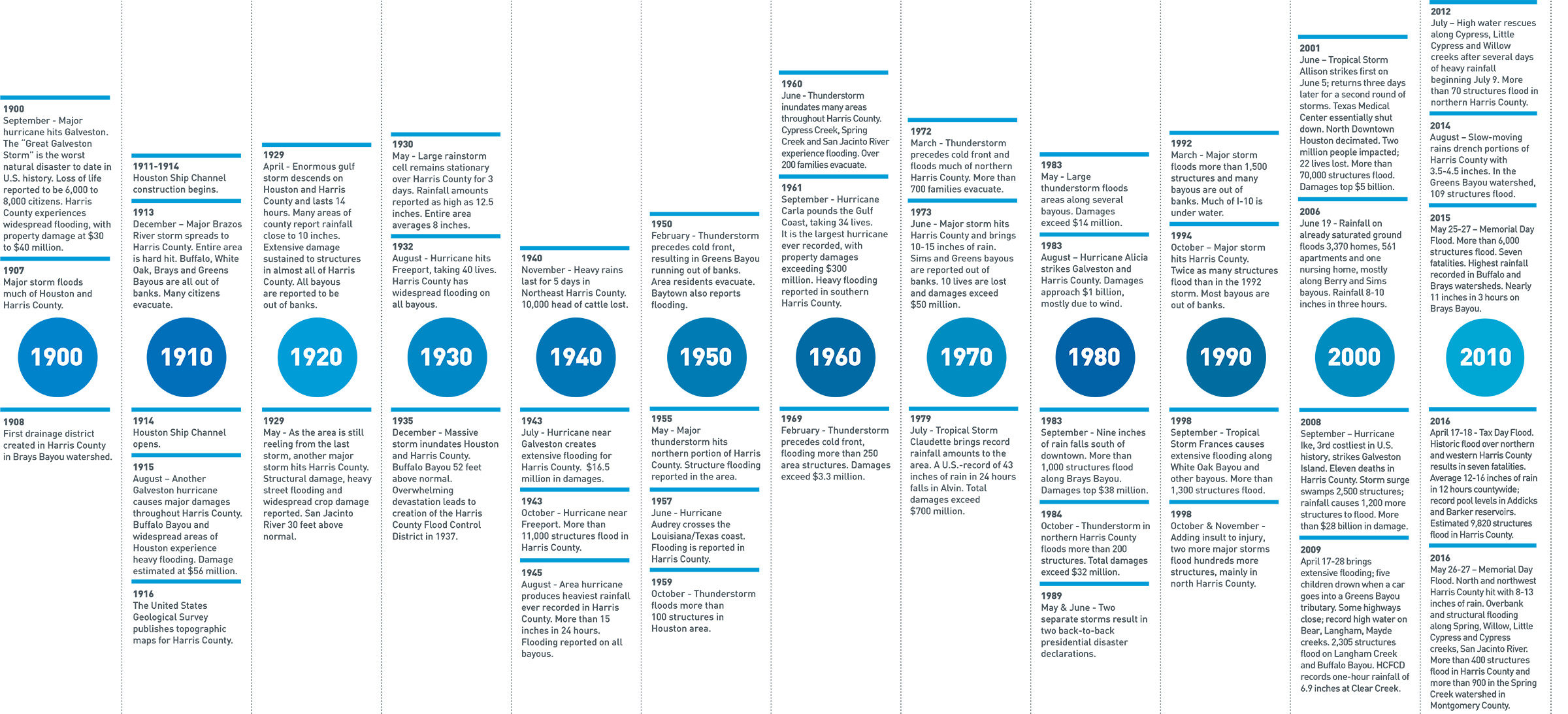

Harris County, Texas is home to over 4.5 million residents, making it the third most populous county in the United States. The area is prone to flood events, with at least 1 major event occurring every two years, dating back as early as the 1800s. 12

Harris County Public Health (HCPH) is the primary agency responsible for protecting the public’s health in the event of a widespread public health emergency.13 The department employs 700 public health professionals, and sees over 100,000 patients across 16 wellness clinics & WIC sites. HCPH has historically responded to public health issues such as rabies, mosquito-borne illnesses, air and water pollution, disease outbreaks, water and food-borne illnesses, tuberculosis, polio, and other communicable diseases. However, emerging challenges in the field, such as the increased severity of flooding and other natural disasters have activated a widened scope of responsibility.14

Less than 10 percent of Harris County’s medical centers were shut down or evacuated during Harvey

A Focus on Response

In the days leading up to Hurricane Harvey - a category 4 hurricane that made landfall in Texas on August 26, 2017 - the health department sent out several messages warning residents to avoid hazards presented by flood waters such as downed power lines, sewage contamination, rusted nails, and animals dwelling in the water such as spiders, snakes and alligators.

The breadth and depth of rainfall brought on by Hurricane Harvey was remarkable, pouring 1 trillion gallons of water onto Harris County over a 4-day period.15 It was estimated that this unprecedented storm was the 3rd costliest storm in U.S. history, causing more than 120,000 structures and 185,000 homes to flood after it hit in August 2017. In addition to the structural damage caused by the storm, there were 13,000 rescues made and 300,000 residents left displaced. Businesses and schools were shut down - some for more indefinite periods of time than others - as is the case with the Harris County Criminal Justice Center. Some estimates warn that the Center could remain closed for two more years during flood-related repairs, leaving 30 judges and hundreds of staffers temporarily displaced16.

Harris County was one of the largest communities impacted by Hurricane Harvey’s devastating rainfall, with an estimated 25-30% of the county’s land being submerged in water. During the storm, the HCPH operated as an emergency response team, coordinating with hospitals and healthcare systems to conduct health and medical operations at the mega shelter established at NRG stadium in Houston, TX. Their large-scale disaster coordination extended to animals as well; they worked with animal rescue organizations to manage rescue efforts during and in the aftermath of the hurricane.

Despite the coordinated efforts that took place during the storm, the days and weeks following the storm were most critical to HCPH, as a variety of public health dangers were heightened in the wake of the hurricane. Flood waters containing sewage and bacteria-filled runoff posed a severe threat to both physical and environmental health. E. Coli amounts 125 times higher than Environmental Protection Agency recommended exposure amounts were found in one small sampling of flood water, and a flesh-eating bacteria linked to floodwaters even claimed the life of a 77 year old woman shortly after the storm.17 Additionally, HCPH executive director Dr. Umair Shah reported seeing an increase in floodwater-related illness like respiratory disease and skin and gastrointestinal infections post-Harvey, triggering needed disease surveillance efforts within the community healthcare facilities and area shelters.18

Keeping medical services available to residents was both a priority and one of the county’s greatest accomplishments last August. Dr. Shah reports that less than 10 percent of Harris County’s medical centers were shut down or evacuated during the storm, which can largely be attributed to the abundance of experience that community providers have had offering care during natural disasters.19 Storms like Harvey make it harder for vulnerable populations to receive needed treatment for preexisting health conditions, which is why healthcare accessibility is an important feat.

In another highly publicized win for the county, reports show that 97% of Harris County TB patients participating in a Tuberculosis Elimination Program were able to take their meds during Hurricane Harvey, preventing the highly transmissible disease from being spread in the aftermath of the storm. The win was attributed to an investment in telehealth technology, which was adopted in recognition of the need to reach vulnerable populations during severe emergencies. It was also born out of Harris County Public Health department’s strategic priority to maximize resources through the use of emerging technologies.

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious bacterial disease that most commonly affects the lungs. The treatment regimen for TB can range from six to nine months or longer, and interruptions in the regime can prolong the treatment and even create bacterial resistance. Patients in the Tuberculosis Elimination’s Telemedicine Program were given a month’s worth of medication prior to the weather emergency. During the hurricane and its aftermath, county staff reached out to patients via mobile phone, landline, or push text messages via the telemedicine app, which kept them connected to their provider. The use of telemedicine was cited as the reason for the remarkable compliance rate by HCPHD staff, serving as a means of cost savings and added layer of resource that allowed for the continuation of operations during and after a storm. 20

Source: Harris County Flood Control District - to view the full timeline, visit: www.hcfcd.org/flooding-floodplains/harris-countys-flooding-history/

A Focus on Recovery

Mosquito control emerged as another important health issue, as the standing water left behind by Hurricane Harvey created favorable condition for mosquito eggs to hatch. The large numbers of mosquitoes appearing after the storm threatened to hamper recovery efforts. While most mosquitoes that emerge after floods don’t spread disease, areas of standing water can also increase those that are capable of spreading diseases like West Nile virus and Zika.21 One method of mosquito control employed by the HCPH department is aerial spraying, which can rapidly reduce the number of mosquitoes in a large area. It’s the most effective method when large areas must be treated quickly.

The HCPH department engaged residents in health education campaigns and mobile clinics in an effort to bring safety and medical interventions directly to the community. One hundred HCPH employees went door-to-door handing out cleaning supplies and hand sanitizer. Mobile clinics helped with surveying the community for health concerns, offered immunizations for both residents and their pets, and brought preventative medical supplies to non-mobile residents.22

In spite of these early wins, ongoing recovery efforts call attention to the need for public health prevention and preparedness plans. The Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response (OPHPR) within HCPH develops comprehensive and collaborative approaches to prepare the community of Harris County to safely respond to and recover from public health emergencies, and ensures effective, coordinated responses to weather-related disasters. The department makes public information accessible in both English and Spanish on an abundance of health and safety topics, from disaster kits to food safety and flood recovery. Additionally, the department conducts regular Community Assessments for Public Health Emergency Response (CASPER), to evaluate the community’s level of emergency preparedness. 23

Conclusion

In the long term, recovery through monitoring of physical and mental health impacts and investments in public health infrastructure and capacity will be necessary. While it is estimated that the probability of another event with the incredible magnitude of Hurricane Harvey’s rainfall occurring in any given year is extremely low (less than 0.01 percent change of annual occurrence), the Harris County Public Health Department is working to prepare and equip its residents for the next public health disaster and future health emergencies.24

Population: 502,146

Square miles: 1,768

Background

The Sonoma County Departments of Health and Human Services are committed to protecting and supporting the health, safety and well-being of individuals, families and the community through a broad range of innovative programs and services. A major priority of the departments is preparedness to ensure quick and effective response to disasters.25

A Focus on Response

On October 8-9, 2017, three wildfires – the Tubbs, Pocket and Nuns Fires – broke out across Sonoma County and could not be contained for more than three weeks due to high winds. Over the course of their burn, the wildfires caused the destruction of over 110,000 acres, the loss of an estimated 6,500 structures and 23 fatalities.26 Mandatory evacuations were ordered for large portions of the county. At the height of the fires, the county and its non-profit partners operated 37 shelters and serviced over 4,000 individuals. Many of the evacuees were in and out of the shelters multiple times as mandatory evacuations were lifted and then re-engaged.

"Health care first responders are every bit as critical as firefighters, police officers, and EMTs in a disaster.”

– Sonoma County Supervisor Shirlee Zane

County health and human services employees – many of whom were among those impacted by the fires – staffed the shelters. It was important to the county to have a mobile staff in order to reach as many residents as possible. As the fires raged into a second week, the county also opened a Local Assistance Center (LAC) in partnership with FEMA and the California Office of Emergency Services (Cal OES) to help those who lost their homes begin to recover. The LAC served as a one-stop shop with critical services, including, but not limited to: crisis and trauma counseling; department of motor vehicle services; FEMA application assistance; and other wraparound services.

Case managers and health providers were available at both the evacuation shelters and at LAC to provide support to those who lost their homes and assist with them vital medications, paperwork – such as identification, birth certificates and death certifications — and the ability to receive paperwork via mail. Sonoma County Human Services Department Director Karen Fies said, “It was critical that we had [staff] in the evacuation shelters as they were vital to ensure that older adults and those with chronic conditions who fled without their medications were able to get new prescriptions written and filled, especially when many pharmacies were closed and others would not deliver.”

Due to the fires, many individuals needed to register for supplemental nutrition, medical and other safety net services that they had not needed before; the two biggest observed enrollments were to Disaster SNAP and emergency unemployment insurance. At the LAC, Sonoma County was able to observe which populations accessed which services across county departments. This resulted in a better-informed Safety Net program, which seeks to strengthening collaborative service delivery strategies and case management across Sonoma County departments.27 Over the course of the county’s two weeks of disaster response, the Department of Health Services – from its medical response teams to its public health and disease control nurses – committed over 33,000 hours responding to the community’s health needs.

Public Health Emergency DeclarationsDuring a disaster event, the HHS Secretary can issue a Public Health Emergency Declaration which opens up special funds and provides local governments with extensions and waivers for certain activities in order to ensure beneficiaries and their health care providers can meet emergency health needs. Learn more |

As the wildfires continued their destructive path, the Bay Area Air Quality Management District issued regular smoke advisories, advising residents – especially elderly persons, children and individuals with respiratory illnesses – to take extra precautions to avoid exposure by staying indoors and closing all doors, windows and air vents to prevent outside air from moving inside.28 If anyone did have to go outside, the county recommended that individuals wear disposable respirators to protect against the harmful air quality. Even following the fires, many residents remain concerned about the air quality and the health risks potentially resulting from inhalation. On October 15, 2017, HHS declared a public health emergency for the State of California.29 The county is doing its best to keep residents as informed as possible, but because the responsibility for gathering air quality data is split among the various federal, state and local agencies, the collective impact is hard to quantify.30

A Focus on Recovery

Air quality was not the only environmental public health danger that Sonoma County residents faced. The ash and debris the fires left behind contained toxins from materials such as batteries, paint, solvents, flammable liquids, electronic waste and any materials that contain asbestos and lead.31 The removal process has been two-phased: first the removal of household hazardous waste and then the removal of other fire-related debris. Immediately following the fires, residents were ordered not to tackle debris removal themselves as sifting or shoveling the ashes may release the harmful toxins into the air and “jeopardize the ability of property owners to obtain financial assistance from FEMA.”32 They were then given the option of either signing up for a government-sponsored clean up or hiring a private contractor. Those who chose to participate in the government program were required to complete and submit a right-of-entry form and would not be subject to out-of-pocket costs.33 On November 3, 2017, less than a month after the fires began and only days after the fires were declared fully contained, the county hosted a “debris removal resource fair” to walk residents through their options. It was imperative to the county that debris removal start as quickly as possible due to the public health threat it posed, not only to air but also to water quality due to toxins, nutrients and excess silt entering the watershed via stormwater.34

Mental health services – especially for the elderly – continue to be a top priority. In the month following the fires, calls to the Sonoma County Department of Health Services Behavioral Health department doubled. To help the county and its residents recover, the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors engaged trauma experts Robert Macy and Melissa Brymer to help local officials develop a long-term mental health plan and to provide crisis counseling assistance and training to county staff and residents via live and televised clinics.35 Local mental health providers are also continuing to band together to provide free or reduced cost services to local residents affected by the fires. Sonoma County Supervisor Shirlee Zane sees the need for ongoing health and human services for at least a year following the fires – or any crisis of this magnitude – as reality sets in.

In line with Oklahoma County’s advice, Sonoma County Department of Health Services Director Barbie Robinson also stressed the need to have a strong COOP plan as normal operations resume. “Having staff understand the transition from response back to normal operations is key.”

Sending people out into the community during the response phase is critical to a successful recovery.

Conclusion

Sonoma County Departments of Health and Human Services learned two main lessons from their response to the county’s 2017 fires. First, the value of mutual aid cannot be overstated. With the overwhelming number of residents in need of county services – and the number of county staff among those affected, it would have been impossible for the county to respond efficiently and effectively without outside help. Realizing this, the county enlisted local nonprofits and fellow California counties to help provide medical and social services. Seeing the value of mutual aid firsthand, the county now plans to put formal agreements in place to streamline its response even further.

Second, training is vital to effective response. If leadership and staff do not understand the incident management structure and know their role in a disaster, the county’s ability to respond is hampered from the beginning. Everyone needs to have a role – even if that role is to maintain regular service – but at the same time everyone must be flexible and nimble as needs and circumstances change. For example, the Sonoma County main administrative campus and two of its three hospitals were mandatory evacuation sites for the duration of the fires. As a result, the Department of Human Services administrative office, which was not evacuated and had a backup generator for power, became the operations center for the department and any other County staff who needed a space to work. During this time, county staff were mobilized across the county and to keep track of them the county instituted twice daily check-ins – once in the morning and once in the evening – to inventory staff and programs. Without proper training and protocols, the county would not have been able to provide service as effectively as it did.

Conclusion

As the shortest phase of the emergency management cycle, the response phase necessitates active, in-depth planning and preparedness efforts. A county can measure the success of its mitigation and preparation based on the response phase. If counties do not have the proper plans in place to protect public health before a disaster strikes, there is little they can do to improve their response during an event.

One of the most important strategies a county can pursue pre-disaster is education and outreach. Counties should have residents prepared to tackle the first 72 hours of a disaster on their own. Residents should know what to do in case of an emergency, from having the necessary supplies to knowing the nearest evacuation route and emergency shelter locations. Similarly, county staff and volunteers should know their roles and responsibilities, including when to report where. Once response moves into recovery, the county and its emergency management, public health and human services departments can begin to return to normal operations – and improve their emergency operations, disaster recovery and continuity of operations plans in anticipation of the next event.

Additional Resources

Harris County Public Health http://publichealth.harriscountytx.gov/

Oklahoma City-County Public Health https://www.occhd.org/

Sonoma County Department Human Services http://sonomacounty.ca.gov/Human-Services/

Sonoma County Department of Health Services http://sonomacounty.ca.gov/Health-Services/

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) https://www.phe.gov/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/

Federal Emergency Management Agency Disaster Declaration Visualization Tool https://www.fema.gov/data-visualization-disaster-declarations-states-and-counties

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/

Community Assessments for Public Health Emergency Response https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/hsb/disaster/casper/

Volunteer Organizations in Active in Disaster https://www.nvoad.org/

Medical Reserve Corps https://mrc.hhs.gov/

Endnotes

1. “Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Overview,” NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/.

2. “2017 U.S. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters: a historic year in context,” NOAA Climate.gov, https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2017-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters-historic-year.

3. “FEMA Disaster Declarations Summary - Open Government Dataset,” FEMA, https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/28318.

4. “Hurricane Harvey’s Public-Health Nightmare,” The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/09/hurricane-harveys-public-health-nightmare/538767/.

5. “A Public Health Lesson from Hurricane Harvey: Invest in Prevention,” Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2017/09/a-public-health-lesson-from-hurricane-harvey-invest-in-prevention.

6. “Health and Safety Concerns for All Disasters,” CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/alldisasters.html.

7. “Prevent Illness After a Disaster,” CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/disease/facts.html.

8. “A Public Health Lesson from Hurricane Harvey: Invest in Prevention,” Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2017/09/a-public-health-lesson-from-hurricane-harvey-invest-in-prevention.

9. “FEMA Disaster Declarations Summary - Open Government Dataset,” FEMA, https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/28318.

10. This case study was based on an interview with Oklahoma County, Okla., OKC-County Health Department Public Health Protection Director, Phil Maytubby. 23 Jan. 2018.

11. “Data Visualization: Disaster Declarations for States and Counties,” FEMA, https://www.fema.gov/data-visualization-disaster-declarations-states-and-counties.

12. “HARRIS COUNTY'S FLOODING HISTORY,” Harris County Flood Control District, https://www.hcfcd.org/flooding-floodplains/harris-countys-flooding-history/.

13. “2017: Hurricane Harvey,” Harris County Public Health, http://publichealth.harriscountytx.gov/Resources/2017-Hurricane-Harvey.

14. “Public Health Matters: Hurricane Harvey Response,” Dr. Umair Shah, https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/Dr-Shah-TFAH-Harvey-Briefing-Slides-9.27.17.pdf.

15. “HURRICAN HARVEY: COUNTYWIDE IMPACTS,” Harris County Flood Control District, https://www.hcfcd.org/hurricane-harvey/countywide-impacts/.

16. “Harvey-Damaged Courthouse in Houston Could Stay Closed Two Years,” NBC, https://www.nbcdfw.com/weather/stories/Harvey-Damaged-Courthouse-in-Houston-Could-Stay-Closed-Two-Years-471305524.html.

17. “One Month Later, Harvey-Related Health Concerns Still Remain,” Houston Public Media, https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/articles/news/2017/09/27/239232/one-month-later-harvey-related-health-concerns-still-remain/.

18. “Houston health officials warn homeowners about slight uptick in diseases after Harvey,” Yahoo! News, https://www.yahoo.com/gma/houston-health-officials-warn-homeowners-slight-uptick-diseases-122304073--abc-news-topstories.html.

19. “Months after Harvey, health care challenges persist,” The Texas Tribune, https://www.texastribune.org/2017/11/30/livestream-health-care-after-hurricane-harvey/.

20. “Telehealth success story: 97% of Harris County TB patients took their meds during Hurricane Harvey,” Healthcare IT News, http://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/telehealth-success-story-97-harris-county-tb-patients-took-their-meds-during-hurricane-harvey.

21. “Questions about Aerial Mosquito Control,” Texas Health and Human Services http://www.dshs.texas.gov/news/releases/2017/Questions-AerialMosquitoControl.aspx.

22. “Harris County goes door-to-door looking for Harvey health concerns, ABC 13 Eyewitness News, http://abc13.com/health/inspectors-surveying-area-for-harvey-health-concerns/2421531/.

23. “Office of Public Health Preparedness & Response,” Office of Public Health Preparedness & Response, http://publichealth.harriscountytx.gov/About/Organization/OPHPR.

24. “HURRICANE HARVEY: PREPARING OUR REGION FOR FUTURE EVENTS,” Harris County Flood Control District, https://www.hcfcd.org/hurricane-harvey/preparing-our-region-for-future-events/.

25. This case study was based on an interview with Sonoma County, Calif., Human Services Director Karen Feis, Health Services Director Barbie Robinson and Supervisor Shirlee Zane. 9 Feb. 2018.

26. “California Statewide Fire Summary, Monday, October 30, 2017,” CalFire, http://calfire.ca.gov/communications/communications_StatewideFireSummary.

27. “County Strategic Priority: Securing our County Safety Net,” Sonoma County, http://sonomacounty.ca.gov/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=2147536560.

28. “Smoke Advisory,” Bay Area Air Quality Management District, http://www.baaqmd.gov/~/media/files/communications-and-outreach/publications/news-releases/2017/smoke_171009-pdf.pdf?la=en

29. “Acting Secretary Hargan declares public health emergency in California due to wildfires,” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2017/10/15/acting-secretary-hargan-declares-public-health-emergency-california-due-wildfires.html

30. “Health Risks of Toxic Ash Feared in Wake of Sonoma County Fires,” The Press Democrat, http://www.pressdemocrat.com/news/7606891-181/health-risks-of-toxic-ash.

31. “U.S. EPA to oversee toxics cleanup after fires in Sonoma and Napa counties,” The Press Democrat, http://www.pressdemocrat.com/news/7534834-181/us-epa-to-oversee-toxics

32. “Health Officer Order For Debris Removal,” Sonoma County Recovers, https://www.sonomacountyrecovers.org/health-officer-order-debris-removal/

33. “Sonoma County Board of Supervisors sets deadlines for wildfire victims to join debris removal programs,” The Press Democrat, http://www.pressdemocrat.com/news/7594462-181/sonoma-county-board-of-supervisors

34. “Damage to creeks, water supply analyzed after Sonoma County fires,” The Press Democrat, http://www.pressdemocrat.com/news/7622435-181/damage-to-creeks-water-supply

35. “Mental health issues increasing as Sonoma County enters new phase of fires’ aftermath,” The Press Democrat, http://www.pressdemocrat.com/news/7650663-181/mental-health-issues-increasing-as

About NACo's Resilient Counties Initiative

The NACo Resilient Counties Initiative works to bolster counties’ abilities to thrive amid changing physical, environmental, social and economic conditions. Focusing on sustainability and disaster management, the Initiative strengthens county resiliency by building leadership capacity to identify and manage risk, while allowing counties to become more flexible and responsive. Through its solutions-oriented programming, it tackles a wide range of issues, from the green economy and nature-based infrastructure to water quality and flood management. It is important for counties to be prepared to address these issues in a manner that can minimize the impact on local residents and businesses, while helping counties save money. Learn more

About NACo's Healthy Counties Initiative

NACo’s Healthy Counties Initiative creates and sustains healthy counties by supporting collaboration and sharing innovative approaches to pressing health issues. It focuses on enhancing: public-private partnerships in local health delivery; access to, and coordination of, care for vulnerable populations in the community, including through health services in hospitals, community health centers and county jails, while concentrating on cost-containment strategies; and community public health and behavioral health programs. By addressing these and other relevant topics, Healthy Counties empowers county leaders with resources for promoting and advancing health policies and programs that meet the needs of their residents and employees. Learn more

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Jenna Moran, Program Manager for Resilience and Blaire Bryant, Program Manager for Health, with guidance from Sanah Baig, Program Director for Community Resilience and Economic Development, Michelle Price, Associate Program Director for Health, and Maeghan Gilmore, Program Director for Health, Human Services and Justice.

Special thanks to the following individuals for providing their time and expertise:

Karen Fies, Human Services Department Director, Sonoma County, California

Jennifer Kiger, Chief of the Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response, Harris County Public Health

Phil Maytubby, Public Health Protection Director, Oklahoma City-County Public Health

Barbie Robinson, Health Services Director, Sonoma County, California

Hon. Shirlee Zane, Supervisor, Sonoma County, California