Money Matters - Jan. 25. 2016

Upcoming Events

Related News

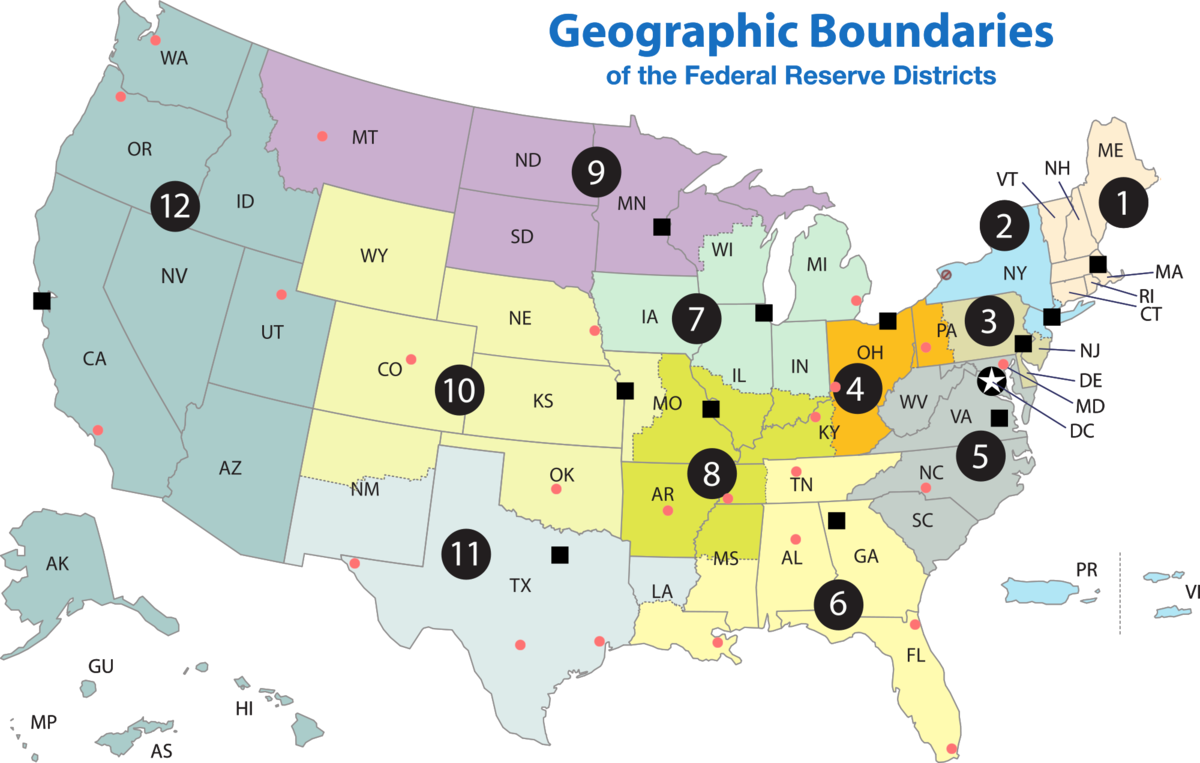

The Federal Reserve Bank of the United States (Fed) has a discernible impact throughout the entire economy. However, this impact is rarely recognized in full. Congress has delegated management of the nation’s monetary system to this central bank with a dual mandate: 1) stable prices; and 2) full employment. The Fed uses a number of tools to achieve these aims, which include adjustment of the amounts of monetary stock (money), purchases of specific asset classes for the Fed balance sheet and influencing interest rates.

The United States of America prides itself on being a free market economy. In large part this is true. This nation enjoys a prosperity, abundance and level of opportunity exceeding that of any other similarly large nation in the history of mankind.

The United States of America prides itself on being a free market economy. In large part this is true. This nation enjoys a prosperity, abundance and level of opportunity exceeding that of any other similarly large nation in the history of mankind.

The ability of individuals to use their skills and capital to engage in voluntary trade, mostly free of confiscation or hindrance by the state or fellow citizens, has produced this abundance.

But the indirect — and sometimes direct impact — of the Federal Reserve on economic conditions cannot be ignored.

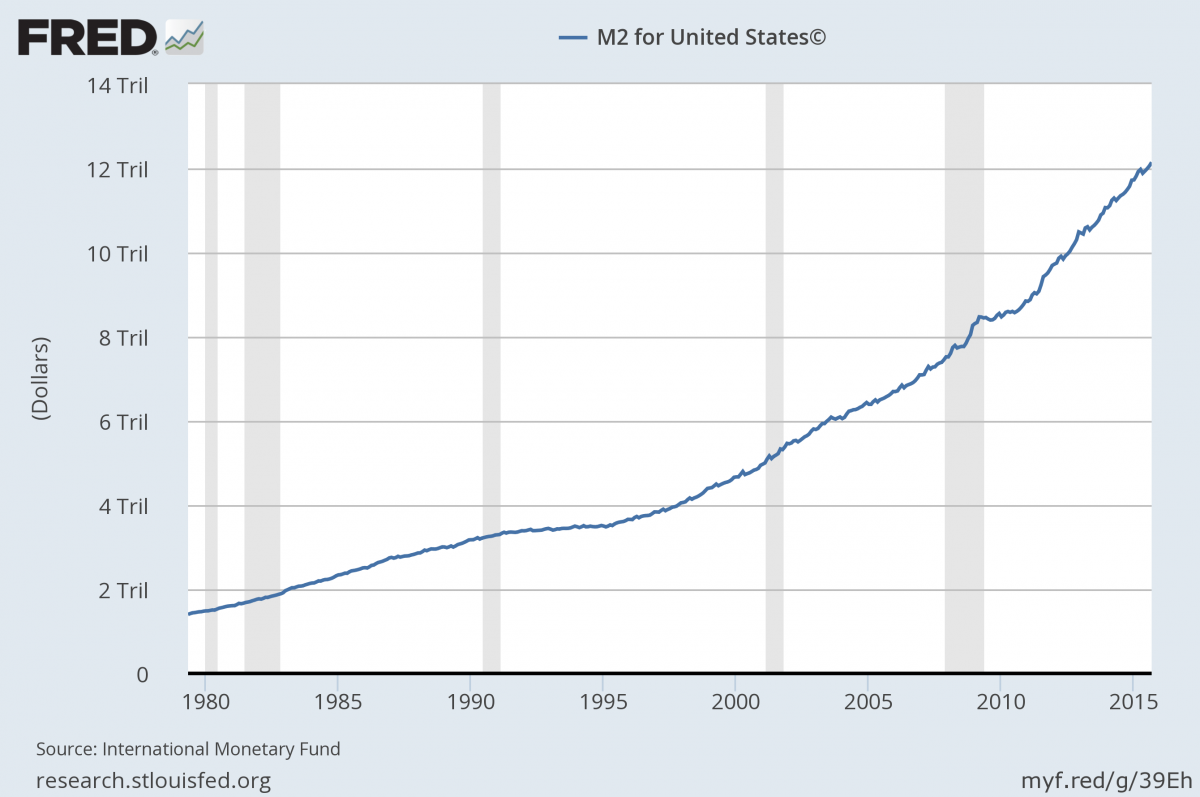

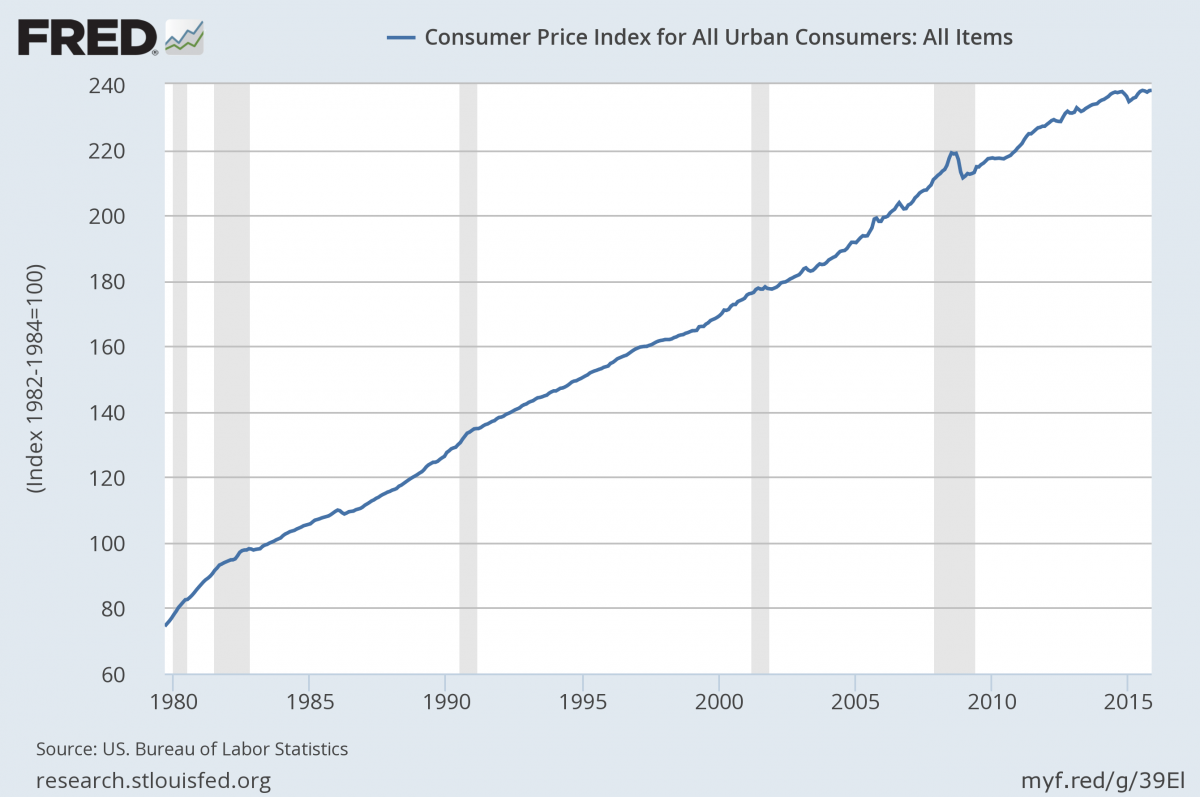

Perhaps the most important manner in which the central bank affects daily life is the steady increase in prices over long spans of time. As the supply of money created by the Fed increases at a rate higher than the absolute growth of the economy, prices in general will increase. Simply put, relatively more units of currency are chasing each unit of economic output. Much of this inflationary result is masked by short- to-medium term fluctuations in commodities such as food and energy. Other inflationary aspects are mitigated by improvements in technology or production efficiency. But over the long run, the trend of higher prices is clear.

Of course, this inflationary effect does more than just increase prices for consumers and producers. It punishes savers and rewards debtors by eroding the value each year of every dollar saved while diminishing the real value of debts incurred. For instance, the purchasing power of $1 declines to just $0.74 after a decade of 3 percent annual inflation. For unsophisticated investors, this serves to erode years of delayed consumption placed in savings accounts rather than equity markets.

And who is the winner in this scheme? None other than the federal government at the present. Washington, D.C. benefits in two primary ways. First, consider that the federal deficit has exploded over the past four decades — now eclipsing 100 percent of GDP. Inflation e

And who is the winner in this scheme? None other than the federal government at the present. Washington, D.C. benefits in two primary ways. First, consider that the federal deficit has exploded over the past four decades — now eclipsing 100 percent of GDP. Inflation e

ffectively cuts about 2 percent of the accumulated deficit off the top each year.

On a more than $18 trillion federal debt, this represents a nearly $400 billion annual boon to the government. Ultimately, this is an enormous hidden tax on the populace and hits all wealth strata. As Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman put it, “Inflation is taxation without legislation.”

Secondly, the Federal Reserve further reduces the borrowing costs of the federal government by purchasing government bonds. Artificially heightened demand, courtesy of the Fed, pushes the price of these bonds up. Of course, interest rates on bonds are inverse to the price of a bond. As a result, interest costs on the federal debt are lower than otherwise. Once again, enormous cost savings accrue to the federal government to the detriment of the private sector.

The Federal Reserve also affects interest rates across the broader economy primarily through targeted asset purchases, adjustment of reserve requirements and control of the interest rates charged by banks on overnight loans of federal funds. The Fed conducts these activities presumably with the intent to achieve the congressional dual mandates. However, this meddling is not without risk. History is replete with examples of the damage caused when governing powers attempt to set price controls. And the most important commodity to a well-functioning free market economy is capital.

Like other goods, the cost of money (the interest rate) provides important signals to market participants about the level of demand for capital by specific businesses and sectors. Manipulating these costs — presently by pushing that cost lower through low interest rates — impedes the ability of the market to determine which sectors truly can most efficiently use that capital. All things being equal, a business being willing to pay a relatively higher interest rate on borrowed capital would be expected to generate more economic growth than another business being willing to pay a lower rate.

For the good of the economy, capital should flow to those segments most able to profitably put such capital to use. In addition, the interest rate demanded by lenders in a free market will reflect the perceived risk of an investment opportunity.

For the good of the economy, capital should flow to those segments most able to profitably put such capital to use. In addition, the interest rate demanded by lenders in a free market will reflect the perceived risk of an investment opportunity.

An artificially low rate misallocates this capital—causing it to often flow to ventures, which are more risky than the associated interest rate.

These asset bubbles — in large part enabled by the central bank’s attempted management of the economy — have repeatedly occurred. The tech bubble ending in 2001 and the real estate bubble leading into the Great Recession are but two recent examples. Milton Friedman compiled numerous examples in prior centuries and by central banks across the globe in his book Monetary Mischief.

State and local governments can mitigate the dangers presented through prudent fiscal management. Treasury coffers may swell from taxable income produced by central bank induced bubbles — including real estate, commodities or equities. By holding the line on spending growth even in the face of temporary influx of funds, governments can serve their constituents without painful cutbacks through both booms and busts.

Joel Griffith is general program manager for NACo-FSC, supporting FSC’s Multi-Bank Securities eConnectDirect for county treasurers. Before joining NACo, Griffith worked as a research associate with The Heritage Foundation.

Attachments

Related News

White House launches federal flood standard support website and tool

On April 11, the White House launched a new website and mapping tool to help users with the ongoing implementation of the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard (FFRMS).